During the 1950s James Stewart appeared in a series of films directed by Anthony Mann, eight in all, and five of them Westerns. The non-Western titles included Strategic Air Command, a semi-documentary depiction of the American Air Force, a melodrama about oil drillers called Thunder Bay and the most successful of the films the two made together, The Glen Miller Story.

It’s the Westerns that Stewart and Mann collaborated on that are of more interest and worthy of consideration for all of those cowboy fans out there.

James Stewart enlisted in World War II and eventually ended up as a bomber pilot, and was deployed to England from where he flew a large number of missions over Germany.

A number of biographies on the actor comment that he suffered from severe post-traumatic stress after the war ended and that this informed his onscreen performances for a number of years afterward.

There is a suggestion, for example, that Stewart channelled a lot of his post-war angst in the attempted suicide sequence in It’s a Wonderful Life.

I feel he also did the same with certain aspects of the characters he played in the Anthony Mann Westerns.

Watching these films one can see Stewart leaving behind the ‘aw shucks ma’am’ persona of his pre-WWII films and depicting tougher and more psychologically complex characters, possessed of a certain hysterical edge which bordered at times on the edge of the deranged, a trait which was hitherto hidden from the audiences of the time.

Although Stewart is still kind of likeable in these films with Mann, the actor plays characters that are a million miles away from Destry Rides Again (1939), that’s for sure.

Winchester 73 (1950)

Filmed in black and white and with a co-writing credit for Borden Chase, who contributed to a number of other Anthony Mann Westerns as well as Red River for Howard Hawks, the story is very basic.

James Stewart as Lin MacAdam, along with his riding partner High Spade, arrive in Dodge City on the trail of someone, but at that point, we’re not exactly sure who they’re looking for, or why.

They chance upon a shooting competition to win a brand new Winchester rifle which is being held to commemorate the centennial year of American Independence.

They are immediately relieved of their handguns by Wyatt Earp, played here by Grandpa Walton himself, Will Geer.

Walking into the nearest saloon MacAdams recognises the man he’s been looking for, Dutch Henry Brown, played by Stephen McNally. Earp intervenes before an altercation can take place after which MacAdams wins the marksmanship contest. Brown comes second and then steals the Winchester from MacAdams, after which it all kicks off.

The black and white photography, low angle shots and use of deep focus by cinematographer William Daniels, who went on to make another four films with Stewart / Mann, bestows an element of film noir on the movie, which is appropriate considering Mann’s previous excursions into noir territory with films such as Desperate, Raw Deal and T-Men.

The scene in which Dutch ambushes MacAdams in his hotel room and steals his rifle is particularly effective, the director capturing in close-up the faces of the combatants as they struggle with each other for ownership of the rifle.

This emphasises not only the brutality of Dutch but more significantly the barely controlled rage and anger that simmers beneath the surface of Stewart’s character.

It’s probably true to say that in some ways the rifle itself is actually the star of the film, seeing as it passes through the hands of numerous individuals until being returned to its rightful owner.

The ensemble of actors that come into contact with the stolen rifle makes their mark though.

John McIntire almost steals the show as a sleazy gambler and gun runner who wins the Winchester from Dutch Henry in a card game, then loses his life when he refuses to sell it to an Indian chief played by Rock Hudson, appearing here early on in his career, pre-nose job.

The rifle ends up in the possession of a certain Steve Miller who has let the side down earlier by abandoning his sweetheart, played by a very young Shelley Winters, to the mercy of Rock and his marauders.

Steve returns in the nick of time to save Shelley from a fate worse than death only after spotting the cavalry troop nearby, but from that moment on he is the token coward of the county, although he redeems himself in the ensuing battle between the cavalry and the Indians.

In the final last half hour of the film the story gears up a notch, as if it needed to, by the introduction of Dan Duryea as Waco Johnny Dean, channelling his inner Richard Widmark as a giggling gun-happy psychopath, or as Shelley Winters remarks, the ‘lowest thing standing in a pair of boots’, as well as a ’two-bit four-flushing gunslinger’.

The coward that was Steve gets one in the belly from Waco who then disappears with both the rifle and poor old Shelley, leaving the members of his gang to die in a hail of bullets.

It is now revealed that Lin MacAdam is tracking down Dutch to kill him for shooting Lin’s father in the back. His sidekick, High Spade, starts to question what his father might think of Lin hunting down a man to kill him. ‘You’re beginning to like it’, High Spade tells his friend, calling into question Lin’s state of mind.

Later on, someone remarks that Duryea’s character, Waco, is a little ‘on the crazy side’, putting both him and Lin on level par in terms of their sociopathic attitude towards their fellow man.

Lin eventually encounters Waco and, aware that Dutch is supposed to be meeting this gentleman, finally loses whatever studied cool he may have displayed up to that point.

In a scene that apparently drew gasps of astonishment from audiences at the time, he nearly breaks Waco’s arm, clawing at his face as he tries to get him to tell where Dutch is.

On the way out of the saloon Waco foolishly turns to shoot but Lin beats him to the draw and ends up face down in the dirt.

The brutality of nearly all of the characters in this film is highlighted when Dutch shoots Shelley Winters, wounding her in the arm, as he rides away with Lin in pursuit.

The big reveal is then made: Dutch is actually Lin’s brother, so it’s been a family affair of betrayal and revenge of almost Greek tragedy proportions right from the very beginning, almost like The Searchers but with an even unhappier ending.

Lin and Dutch, whom Lin now insists on calling by his real name, Matthew, shoot it out atop a tower of rocks in the middle of the landscape, Lin ironically finding himself under fire from the very rifle he won at the beginning.

Good triumphs in the end, as it should, with brother shooting brother, Dutch / Matthew falling to his death from a great height.

Lin gets the girl as well, but Stewart’s expression in the final scene as he hugs Shelley Winters could be interpreted as an indication of regret, and quite possibly shame as well, that he has killed his own brother, and in the process finally taking ownership of the gun his own kin tried to kill him with.

This film is not your standard Western oater crowd-pleaser, not by a long shot, but the partnership of Stewart and Mann gets off to a flying start with Winchester ’73.

By sheer coincidence, the film was listed as being shown on tv as I wrote this piece. The review mentions that Stewart felt Anthony Mann and the success of Winchester ’73 saved his career.

I guess that’s probably true, but the success of the film did more than that for him. It actually made James Stewart an extremely rich man. He and his agent made a deal with the studio in which the actor would receive a percentage of the profits, something unheard of at the time. Result: Stewart rode his horse all the way to the bank and the acting community took their turn at running the Hollywood asylum instead.

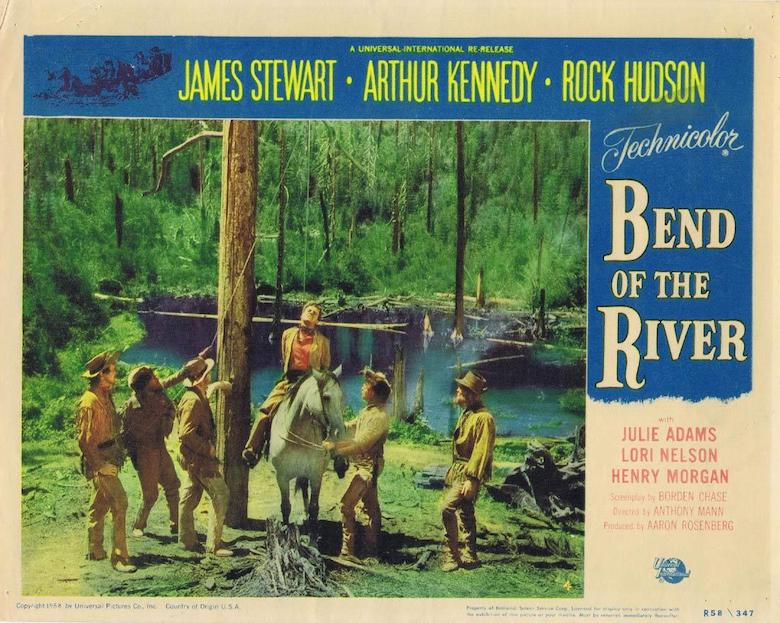

Bend of the River (1952)

The script once more is by Borden Chase and filmed in colour, which means the scenery that features so prominently in Bend in the River isn’t as stark and ominous as the black and white landscape shown in Winchester ’73.

Continuing with the theme of viciousness that runs through the previous film, Bend in the River starts with someone about to be hanged, until James Stewart as Glyn McLyntock intervenes and rescues the man in question, Emerson Cole, played by Arthur Kennedy.

Glyn has taken on the job of helping a wagon train of settlers navigate their way across hostile country to start ranching and farming in Oregon. Glyn takes Cole back to the wagon train, unwittingly introducing a viper into the nest.

The settlers come under attack at night by a band of Shoshone warriors, with Stewart’s love interest, Laura, played by Julia Adams, taking an arrow in her shoulder.

Unlike Joanne Dru who is similarly skewered in Red River, Julia screams like a little girl, so she’s obviously not a paid up member of the Hawksian Women’s Society.

Glyn and Cole go after the attackers, killing all of them with Cole saving Glyn’s life during the encounter. The fact they have saved each other’s lives forms a bond of friendship that Glyn will soon come to regret.

Arriving in the town of Portland Glyn is given the opportunity to transport the wagon train by boat and before you can say ‘Holy John Ford’ up pops Stepin Fetchit working on a steamboat. It starts to become obvious that Glyn is trying to get away from his past, whatever that might have been, and Cole has secrets to keep as well.

The appearance of Rock Hudson as river gambler Trey Wilson introduces another element into the narrative that promises trouble along the way. And trouble comes real quick, Hudson accusing another gambler, who has just recognised Cole as a Missouri raider, of cheating.

The gamblers draw their weapons, Hudson wounds the other guy then Cole finishes the gambler off with a shot of his own.

The film looks absolutely beautiful and was mainly shot on location in Oregon.

As with Winchester ’73, the landscape is highly prominent and integral to the story.

Director and cameraman frame the characters against the breathtaking views of the snow-capped mountains in the distance, emphasising the struggle the settlers have to face in order to tame the wilderness itself.

The noir element is still there though, Bend in the River appearing to be, among other things, an exercise in deception, which is also a key trait found in practically every noir film ever made.

Glyn isn’t the person people think he is because he has a questionable past. Cole asks him who he’s trying to get away from and Glyn tells him he’s running away from Glyn MacLyntock.

Cole turns out not to be the charmer he initially appears to be either. The gambler who comes across as a benign individual is shot to death for cheating at cards. The kind-hearted trader who takes $5000 from the settlers to deliver food to them once they’ve reached their destination sells the goods on to the highest bidder instead.

Even the Julia Adams character, Laura, gets a case of rampant duplicity, throwing over that nice James Stewart for Cole until she realises the error of her ways and returns to the fold.

It’s a film of two halves – happy settlers buying food in Portland to see them through the winter, then, when the promised supplies don’t turn up when expected, Glyn and his companion ride back to Portland only to discover that gold has been discovered in them thar hills and the goods they purchased are now worth ten times more.

Glyn goes to confront the man who took their money which inevitably ends in a fight, he and Cole and Trey liberating the disputed goods and hightailing it out of town on the steamboat.

There’s a long chase sequence in which various parties double-cross each other, leaving me to wonder if Alastair McLean had an uncredited role in writing the script.

Along the way it becomes obvious Glyn / Stewart is possessed of a short fuse, barely able to control a compulsion to knife someone to death when he’s confronted by treachery.

This last part of the film accentuates the theme of men fighting against the wilderness as well as amongst themselves, Glyn struggling to get the food to the settlers across the rugged landscape while all manner of murder and mayhem attempt to stop him.

After killing Coleman in a fight in the river and being hauled out of the water by Trey the gambler, we see a rope burn on Glyn’s.

A bunch of vigilantes once tried to hang him but the settlers are willing to forgive him his dubious past and welcome him into the community.

A slightly more traditional Western than Winchester ’73, it still has its moments and is worth watching if you’ve not seen Bend in the River yet.

Want more? Part 2 of the James Stewart/Anthony Mann can be found here.