John Ford is obviously mainly known for directing Westerns, some of the most acclaimed of them starring John Wayne. Wayne appeared in 8 of the 14 Westerns John Ford directed in the sound period, with Ford directing his last Western, Cheyenne Autumn, in 1963.

I’m going to take a look at those non-JW Ford Westerns, as well as some of the silent cowboy films Ford before teaming up with Wayne in 1939 for Stagecoach.

Straight Shooting (1917)

Straight Shooting (1917)

John Ford directed quite a few 2 and 3 reel Westerns for Universal Studios starring the popular actor Harry Carey from 1917 to 1921. One of the first of these was Straight Shooting, which miraculously survives in a complete version discovered in Czechoslovakia back in the 1960s.

The main difference here is that this film consists of 5 reels with a running time of just over an hour, making it the first (almost) feature-length film Ford ever directed. As with a lot of the other films Carey made with Ford, he plays a recurring character called Cheyenne Harry, who epitomises the ‘good badman’ figures that we see John Wayne play in later Ford movies such as 3 Godfathers and The Searchers.

Cheyenne Harry is recruited to run off a family of settlers from their land or even kill them if necessary. Harry has a crisis of conscience when he witnesses the father of the settler family burying his murdered son, and switches sides, eventually gunning down ‘Placer’ Fremont, the outlaw leader who murdered the young boy.

We see an example towards the end of the film of Carey’s trademark gesture of holding his his right arm just above the wrist, a gesture referenced by Wayne as he stands framed in the doorway of the cabin at the end of The Searchers.

There were apparently two different versions of Straight Shooting, one in which Harry rides off into the sunset, the other version, released in the 1920s, ending with Harry getting the girl, the sister of the murdered boy. It is the latter version that was discovered in Czechoslovakia.

Ford openly flaunts the directing influences of his older brother, Frank Ford, and D.W. Griffith, in the actions scenes, but even at this early stage in his career there is evidence that the director is very much at home in the Western genre, as his later films would go on to show.

This film was initially available up until a few years ago on a bootleg VHS copy from Balzac Video, which appears to no longer be listed on the internet. There appears to be a DVD on Amazon but one of the reviews states that the film fades out after 45 minutes so it doesn’t sound like the full version to me. Either way the film is definitely worth tracking down, even if it’s just for curiosity value alone.

The Iron Horse (1924)

The Iron Horse (1924)

This is the film that turned John Ford literally into a household name in America. He moved from Universal to the Fox Corporation in 1921 in order to avail himself of a wider choice of subject matter and bigger budgets. Apart from the two films he made for Fox whilst on loan from Universal in late 1920 / early 1921, The Iron Horse was only the third Western he made for Fox out of the ten films he directed from late 1921 onwards.

This epic tale of the building of the first trans-continental railroad across America was produced in an attempt to replicate the success of The Covered Wagon, produced the year before and a big box-office hit for the Paramount Movies studio. The Iron Horse turned out to be Ford’s most successful silent title up until that point, costing approximately $280,000 to produce and returning in excess of $2 million at the box office.

At a running time of about two and a half hours the film earns its title as a super-Western, Ford throwing in everything and the kitchen sink in order to pull the audience in.

We get murder, treachery, comedy, spectacle, gun battles, bar room brawls, romance, politics – you name it, Ford uses it. Like a lot of films set against a background of a real-life event – think Gone With The Wind, Titanic, Michael Bay’s version of Pearl Harbour (actually, don’t think about that one) – the human drama revolves around a young couple who have to battle against the elements in order to find true love.

The leading man, George O’Brien, appears in the first of approximately nine films he made with Ford, serving the cause with the director over a period of forty years, and performing his last role for Ford in Cheyenne Autumn. He plays railway engineer and architect Davy Brandon, who falls foul of the dastardly villain Deroux – or Bauman as he was called in the version made for international release.

Deroux / Bauman had murdered Davy’s father some years before and Davy was only able to recognize him by the fact he only has two fingers on his right hand. The actor playing Deroux / Bauman had actually lost most of his right hand in an explosives accident so he was well-cast in the role.

It’s not worth going into the complete synopsis of the film as if you’re interested in watching it there’s been a recent DVD release from Masters of the Cinema featuring both versions of the film.

I was lucky enough to catch the film at the Sadler’s Wells theatre in 1994 as part of the London Film Festival, in which the screening was accompanied by a live orchestra playing a new soundtrack composed and conducted by John Lanchbery.

I remember quite clearly the silent film historian Kevin Brownlow introducing the film with the comment ‘this films has something to offend everybody’, referencing the by-then politically incorrect depiction of the Irish, Italian and Asian characters featured in the movie.

What is of more interest, however, is the sheer scale of effort that went into the actual production of the film. Ford and his company went out into the back end of nowhere with a full complement of cast and crew to shoot the film in all conditions, literally building a town of their own in order to accommodate everyone.

Rumour has it there was even a brothel available at some point for some of the more lonely crew members wishing to sate their desire for female company.

Ford himself said he would have liked to have written about the making of The Iron Horse itself, suggesting it would have just as interesting as the actual film. Shame he didn’t.

3 Bad Men

Building upon the success of The Iron Horse, Fox put Ford to work on another super-Western a year or so later, this one again centered on a love story played out against a background of real events, in this instance the Dakota land rush of the 1870s.

Unfortunately, the film did not repeat the level of success previously enjoyed by The Iron Horse, despite the film being, in my humble opinion, the better of the two.

George O’Brien again takes the lead, this time playing a cowboy from Ireland by the name of Dan O’Malley. The 3 bad men of the title, Bull, Spade and Mike, rescue a young woman, Lee Carlton, played by Olive Bordern, after her father has been murdered, with George eventually falling in love with her.

3 Bad Men is closer in style to Ford’s later Westerns rather than The Iron Horse. Whilst the characters of the title are the natural descendants of Carey’s Cheyenne Harry, they also also provide the template for the more complex characters that inhabit Ford’s sound films, Ethan Edwards in particular.

Although clichéd and stereotypical at times, the 3 bad men are more memorably drawn than the main figures in The Iron Horse. Similar in a number of ways to the outlaw gang in Sam Peckinpah’s film The Wild Bunch, they accept they are men who are out of synch with the times, and are heroically prepared to endanger their own lives to assure the survival of Dan and Lee.

There are a number of epic set-pieces in the film including an attack on a town which is put to the fire, but the most memorable sequence is the land rush, in which hundreds of settler’s race each other to the parcels of land being given out by the government for free.

In one scene a young baby is accidentally left behind by a couple of parents who speed of on their wagon whilst the infant faces imminent death from the mass of settlers bearing down from behind on horses and wagons.

Just in the nick of time a hand appears from left of screen and plucks the child to safety. Apparently the baby in question was ‘borrowed’ from a stuntman working on the film and, there being no CGI available at the time, there’s no fakery to the scene at all.

Worth checking out if you haven’t seen it yet.

Drums Along the Mohawk (1939)

Drums Along the Mohawk (1939)

John Ford was just as prolific in his early sound career as he was in the silent period. Of course it helped that he was working – most of the time anyway – within the Hollywood studio system so a lot of films were geared up to go in terms of pre-production before the director actually got involved.

Taking all of that into account it’s still amazing that in the space of one year three films by Ford were all released in the same year – 1939. Along with Stagecoach we also got Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.

All of these films are bona fide Hollywood / John Ford classics. And this was before Ford went on to win back-to-back Oscars a few years later with The Grapes of Wrath and How Green Was My Valley.

Not strictly a proper Western, as the action is set in New York state, Drums Along the Mohawk is Ford’s first colour film and tells the story of a community living on the edge of the frontier at the time of the American War of Independence.

A local militia man, Gilbert Martin, played by Henry Fonda, along with his wife Lana, played by Claudette Colbert, fight off attacks by Native Americans and those dastardly British occupation forces whilst tending their farm and producing a family.

As I mentioned in one of my previous articles, Peter Bogdanovich writes that you can trace the whole of American history up to the end of Word War II and beyond through the films of Ford, and Drums Along the Mohawk is the starting point.

The best sequence in the film comes towards the end in which Fonda is obliged to outrun a group of Seneca Indians as he tries to make his way through enemy lines to raise help for his beleaguered community from Fort Dayton.

Ford’s older brother, Francis, suffers a horrific death at the hands of the enemy when he is roped up inside a wagon and burnt to death. This was possible revenge on behalf of John Ford for mistreatment by Francis when the younger Ford first arrived in Hollywood.

My Darling Clementine (1946)

My Darling Clementine (1946)

Most definitely the jewel in the crown of Ford’s non-John Wayne Westerns. Orson Welles, who famously screened Stagecoach numerous times before embarking upon his own directorial debut with Citizen Kane, once praised Ford as ‘the greatest poet that cinema has given us’, and My Darling Clementine is cinematic poetry at its finest.

Using his beloved Monument Valley as a backdrop to the story of Wyatt Earp’s unrequited love with the Clementine of the title, Ford manages to harvest a career-best performance from Victor Mature, of all actors, as Earp’s sidekick Doc Holliday, and a definitive portrayal of Earp himself from Henry Fonda.

Fonda’s performance is note perfect, a role I don’t think John Wayne could have bettered if he’d had the chance. In fact, there’s so much to recommend in this film that I don’t know where to start.

The tension between Earp and Holliday when they meet in a saloon for the first time, Earp calmly conversing at the graveside of his murdered brother as if talking with someone who is still in the land of the living, the relaxed figure of Earp playfully balancing his chair on the porch as he puts one leg then another on the post in front of him, the dance sequence in which an awkward looking Fonda sweeps Clementine across the floor of the half-finished church – small scenes that contribute as a whole to a story that encapsulates the introduction of civilisation into the raucous environment of Tombstone without overtly laying it on the audience at the same time.

The set piece of the film is of course the legendary gunfight at the OK corrals.

According to Ford himself he had actually met Earp early on in his directing career and Earp relayed the details of the gunfight to Ford, who then went on to film the sequence as accurately as possible.

Unfortunately, it’s a known fact that Doc Holliday didn’t perish at the OK corral, as he does in this film, but as they say, ‘when the legend becomes fact’… well, you know the rest. There are actually two versions of the film now available on DVD, one an early cut that Ford signed off on, and the other with a couple of extra sequences that the Fox studio head at the time, Darryl Zanuck, had inserted after Ford left the project.

In Ford’s version Earp and Clementine shake hands at the end of the film as Earp and his surviving brothers return to the wilderness. In Zanuck’s version Earp kisses Clementine on the cheek, an indication to the audience that there’s a chance of a postponed relationship between the two at some point in the future.

On the same DVD there’s also a bonus film called Frontier Marshal, made in 1939 and starring Randolph Scott as Wyatt Earp. Although remarkably similar to Ford’s effort – there are some sequences in Frontier Marshal that foreshadow My Darling Clementine literally shot-for-shot – it’s Ford’s version that wins out in the end.

I can’t recommend My Darling Clementine too highly. If you haven’t seen it yet I envy you. You’re in for a real treat. Classic Hollywood Western film at its best.

Small trivia note: I believe the main walkway for the set of Tombstone was built on the left hand side of the road leading away from the visitors centre in Monument Valley. I heard a few years back that if you dig down into the sand you’ll find pieces of green papier mache used to construct the false cactus plants that adorned the set.

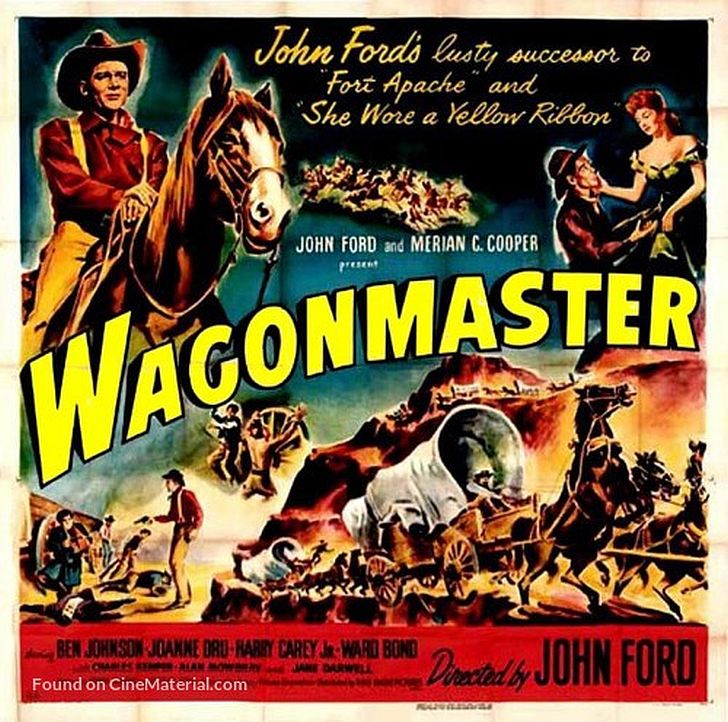

Wagon Master

Wagon Master

This is a real little gem of a film that doesn’t tend to garner much attention these days, mainly because there are no big star names in the cast, but it definitely deserves a wider audience. The main stars of the film, Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr., head up a wagon train consisting of a group of Mormons who are literally looking for the Promised Land.

The wagon train is threatened by the Clegg gang, a family of outlaws on the run after having pulled a robbery and shot an innocent clerk.

The Mormons are accompanied by the members of a travelling medicine show, so cue lots of music and dancing along the trail as the wagon train heads towards it’s destination.

There’s almost a languorous quality to the film that you don’t normally associate with a John Ford movie. If it’s true that the director would on occasion make one film for the studio and the next one just to please himself, I’d say Wagon Master most definitely falls into the latter category.

The ensemble acting of Johnson, Carey, Ward Bond and other members of the stock Ford acting company is embellished by the presence of Joanne Dru (She Wore a Yellow Ribbon), Jane Darwell (Grapes of Wrath) and Alan Mowbray (My Darling Clementine).

The film is also worthy of mention purely for the way in which Ford and his cinematographer capture the grandeur and spectacle of the surrounding landscape, in particular for one of the final shots in the film in which the wagon train eventually reaches its objective. Wagon Master perfectly encapsulates Ford’s emphasis on the importance of community and fraternity in the untamed wilderness and is well worth trying to catch either on DVD or tv if you haven’t yet seen it.

The film is usually mentioned as being the main influence for the 1950s classic Western tv series Wagon Train, which featured Ward Bond as wagon master Seth Adams.

Not only that but when Ford himself directed an episode in 1960 called The Colter Craven Story, it featured numerous stock footage shots from Wagon Master as well. In fact, if you look closely enough, you’ll see Harry Carey Jr. in one of the scenes borrowed from the film in which the wagon train crosses a river.

For those trivia buffs amongst you apparently the famous Native American Olympic athlete Jim Thorpe turns up in Wagon Master as a Navajo Indian.

Sergeant Rutledge (1960)

I might be mistaken but I think I read somewhere way back in the dim and distant path that the African American actor Woody Strode – apparently he was also part Native American – maintained that John Ford had given him the opportunity to be the first black man to portray the title character in a Hollywood film.

I think that honour fell to Dorothy Dandridge who played Carmen Jones in the film of the same name directed in 1954 by Otto Preminger.

Either way Strode felt immensely honoured that Ford had entrusted him with the part of the ‘Buffalo Soldier’ Sergeant Rutledge.

In a 1971 interview, quoted in Joseph McBride’s biography on Ford, Strode said that ‘You never seen a Negro come off a mountain like John Wayne before. I had the greatest Glory Hallelujah ride across the Pecos… [and] I carried the whole black race across that river’.

It’s a shame to say that the film itself doesn’t really live up to to an important step on the road towards equal and civil rights for African Americans, but nonetheless it is a worthy drama in its own right, albeit a box-office flop at the time.

I think part of the problem with the film is that it can’t make up its mind as to whether its an action movie, or a courtroom drama, and so sits uncomfortably between the two.

Although the story should revolve more around Strode’s character, who has been falsely accused of the rape and murder of a white woman, it panders to the mainly white audience of the time by highlighting the relationship between the army lawyer assigned to defend Rutledge, played by Jeffrey Hunter, and the woman he loves, played by Constance Towers.

This emphasis on Hunter and Towers is detrimental to the central character of Rutledge, thus in effect diluting the racial aspect of the film as a whole. This is a shame because I believe it was the first time a Hollywood film had attempted to broach the subject of African Americans fighting another ethnic minority in the name of the settling of the West.

A missed opportunity for all concerned, apart from Strode of course, who gives an impressive performance in the title role.

A little more action and less of the love interest story between Hunter and Towers and this could have been a highly accomplished late career piece of work for Ford.

Strode would not only go on to appear as the faithful ranch hand Pompey in Ford’s later The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, he would also tend to the ailing director during his final years and was there by his bedside when the director passed away in 1973.

Two Rode Together

Two Rode Together

This is the kind of film they coined the phrase ‘curate’s egg’ for – it’s partly good and partly bad in equal measure.

Ford told Peter Bogdanovich that he did the film as a favour for the head of Paramount Studios at the time, Harry Cohn, and the end result shows.

It’s a curious mix of drama and comedy, in some ways pre-echoing the weird ‘Dodge City’ comedy interlude that crops up halfway through Cheyenne Autumn, which I’ll discuss later.

The story is almost a rerun of The Searchers in which an attempt is made to rescue a group of kidnapped white captives from the Comanches. James Stewart as a cynical sheriff and Richard Widmark as a cavalry officer are just too old for their roles, both of them at the time practically bald and going deaf.

Ford embellishes the project with a number of trademark visuals and plot lines – he steals from his own film My Darling Clementine at one point where Stewart warns off a couple of gamblers who have just arrived in town – but the film comes nowhere near being a classic Ford Western.

There are some interesting aspects to the film, however, that might still engage.

Henry Brandon’s Quanah Parker reprises his turn as Scar in The Searchers, and Woody Strode is a suitable nasty Comanche villain. Linda Crystal impresses as the Mexican woman rescued by Stewart and Widmark who faces bigotry and racism once she is returned to white society.

It’s not quite the piece of ‘crap’ that Ford called it after it was released – even the worst of Ford always has something to recommend it – but considering the main cast and a script by Frank Nugent, who also scripted The Searchers, it’s a bit of a disappointment.

For the eagle-eyed among you the scenes in the main town were shot at the Alamo village. Oh, and a great poster by the way. Pity about the film.

Cheyenne Autumn

Cheyenne Autumn

With a running time of just over two and half hours plus intermission, filmed in Super Panavision 70 and bankrolled and promoted by Warner Brothers studios as an ‘event’ movie, here was an opportunity for John Ford, now in his late 60s, to go out with a bang with his penultimate movie.

Ford’s attitude towards the plight of Native Americans had become more liberal over time and the subject matter – the true story of a Comanche tribe who left their reservation in Oklahoma to return to their native land in Yellowstone nearly 2000 miles away – provided the director with a chance to put the record straight regarding the treatment of Native Americans by the military.

As Ford told Peter Bogdanovich whilst on location in 1963 in Monument Valley for the film, ‘Let’s face it, we’ve treated them very badly – it’s a blot on our shield; we’ve cheated and robbed, killed, murdered massacred and everything else.’

With a stellar cast including Richard Widmark, James Stewart, Carroll Baker, Karl Malden and Edward G. Robinson how could Ford fail to deliver what should rightly have been a classic Western to compare with The Searchers and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon?

Well, let’s start with the rest of the casting first. Despite Hollywood occasionally wearing its liberal heart on its sleeve that obviously doesn’t stretch to employing real Native Americans in the main roles.

Instead we get Mexican actors Ricardo Montalban, Dolores Del Rio and Gilbert Roland, Victor Jory, who was American-Canadian and Sal Mineo, born of Sicilian parents.

The film incorporated members of Ford’s beloved Navajo tribe, and to retain a certain element of authenticity the Native American characters spoke their dialogue in what was supposedly Cheyenne language, but was actually Navajo.

I think Cheyenne Autumn could have survived the miscasting of the main Native American characters if that were the only aspect of the film to invite criticism.

However, the movie is badly let down by the misjudged Dodge City sequence, which turns out to be some kind of comic interlude involving James Stewart as Wyatt Earp and Arthur Kennedy as Doc Holliday that has only a tenuous link to the main narrative.

For me, the film never really recovers from that moment on, which is a shame because Ford deserved better at this stage in his career. The film, which had a budget of around $4 million at the time, did not fare that well at the box office and ended the run of Westerns that Ford had directed since 1917.

There is inevitably some aspects of the film that still make it worth viewing, particularly the action sequences filmed in Monument Valley. If possible it should also really be viewed on a large screen to appreciate the pin sharp image captured on 70 mm stock (actually 65 mm if I’m correct) by cinematographer William Clothier, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his work on this film.

So, in the final analysis, an interesting failure but a failure nonetheless.