A question for all you John Wayne fans out there – in what year did our hero make the film Rio Bravo? If you answer 1959, when Wayne starred in the film directed by Howard Hawks, then you’d be wrong.

Rio Grande (1950)

The answer is 1950, which was when Wayne reprised his character of Kirby York in the third of Ford’s unofficial cavalry trilogy. We all know that film as Rio Grande but according to Joseph McBride, who authored what I believe I have already stated is the best biography on John Ford – Searching for John Ford – asserts that whilst Rio Grande was in production it was actually filmed under the title Rio Bravo. According to McBride the original title was dropped due to someone making a legal claim on the name, so instead of Rio Bravo we get Rio Grande instead.

This is the film John Ford had to direct for Herbert Yates, the Republic studio head, in order to get Yates to finance The Quiet Man. The end result, whilst still a classic Ford / Wayne opus, is probably the weakest of the Ford cavalry trilogy movies. The noble Native American figures that Ford depicted in Fort Apache and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, well-rounded characters with a voice of their own, are here replaced by the nameless ciphers of earlier John Ford films such as Stagecoach and Drums Along the Mohawk.

The film is saved by the inspired casting of Maureen O’Hara as Wayne’s estranged wife, Kathleen, their marriage having apparently foundered on the basis that Kirby York fought for the Union during the Civil War whilst Kathleen played the high-falutin’ Southern belle down on the plantation. To complicate matters further their son, played by Claude Jarman Jr., has been assigned to his father’s outpost. The mother arrives to take her son back home to the land of Dixie, the marital discord that follows serving as a template for the relationship Wayne and O’Hara enjoy in their next Ford film, The Quiet Man.

To complicate matters further their son, played by Claude Jarman Jr., has been assigned to his father’s outpost. The mother arrives to take her son back home to the land of Dixie, the marital discord that follows serving as a template for the relationship Wayne and O’Hara enjoy in their next Ford film, The Quiet Man.

Family dramas aside I have to say that Rio Bravo, sorry, Rio Grande, is nonetheless a good old-fashioned Western action film, even if the political landscape in 1950 – the movie went into production a couple of weeks before the outbreak of the Korean war – means that certain film writers make the link between the Apache savages and the nasty North Korean adversaries of the time.

The climax of the film has Wayne and his compatriots tracking down a bunch of Apache renegades who have kidnapped a wagonload of children and taken them across the border into Mexico.

Needless to say our hero wins the day and the frontier is made safe once again, until the next uprising anyway. Ford shot some of the film in his favourite location, Monument Valley, but unlike The Searchers or She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, the landscape doesn’t really take on a character of its own.

One of the things I like about this film is the soundtrack by Victor Young, with the theme for Rio Grande recycled a year later for The Quiet Man as a piece entitled My Mother.

On top of that you have old favourites such as I’ll Take You Home Again Kathleen and The Girl I Left Behind. If you’re interested in the music that Ford uses in his numerous films take a look at a book by Kathryn Kalinak called How the West Was Sung: Music in the Westerns of John Ford. Oh, and of course, John Wayne’s quite good in the film as well.

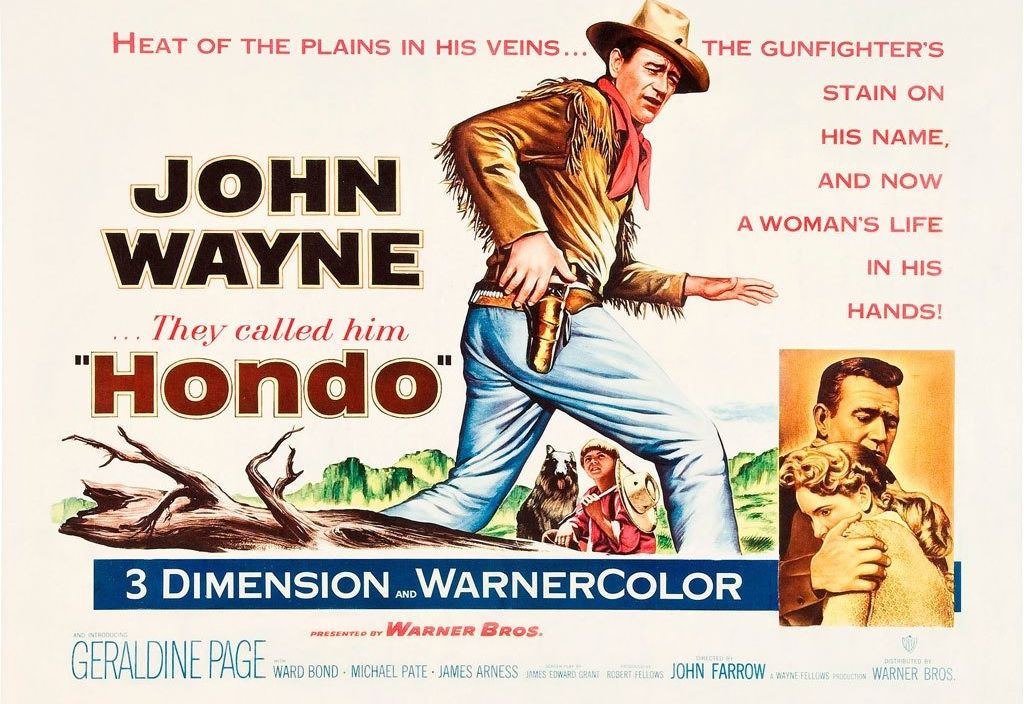

Hondo (1953)

I believe – I’m sure someone out there will correct me if I’m wrong – that this is the only film John Wayne made in the short-lived 3D fad of the time. Imagine Wayne on 4D, his fists shooting out of the screen and destroying everyone in the first row.

Not sure the science of that whole thing works, but still, wouldn’t that have been something. I hadn’t seen this film in quite a while so I checked out it before writing the article and it struck me how much the beginning of the film mirrors the opening sequence of Shane. Assuming that wasn’t intentional I’d have to say the sight of Duke marching steadfastly towards the camera as he appears from the middle of nowhere makes for a much more exciting entrance than Alan Ladd in Shane.

Based upon a Louis L’Amour book, Hondo is an unabashed cowboy and Apache film, with Wayne mouthing the good old-fashioned plain homilies of screenwriter James Edward Grant who thinks that ‘a woman should be a good cook’ and that the leading lady, Geraldine Page, is a ‘homely woman’.

That kind of stuff wouldn’t get past the politically correct film-makers of today but back in the 50s I guess they just told it like it was. If you didn’t know Grant had scripted the film then you’d have got a very strong clue when Wayne launches into a whole bunch of dialogue on his dead Apache wife which sounds almost like a dry run for the ‘Republic.I like the sound of the word’ speech from The Alamo. I should point out that Grant takes the time to put across the view that the Native Americans have not been treated very well by the white man.

Someone remarks that once the new cavalry general arrives it will be ‘the end of the Apache’, to which Wayne replies ‘Yeah. Too bad’. Good to hear James Edward Grant using Wayne to engage in deep political thought on the plight of the indigenous natives. Once the action takes hold, however, Grant’s otherwise outmoded point of view sinks from sight as Duke takes on the whole Apache nation – and wins.

When I was a kid I used to sometimes think that my dad was a bit like John Wayne. Over the years I could never quite articulate why I felt that way, particularly as my dad was a sailor in the Royal Navy, English and about 6 inches shorter than Wayne.

Then I watched Hondo again and realised why. Just like John Wayne, my father also threw a small kid into deep water in order to teach him to swim, in my case the swimming pool just off Margate beach. I suppose the fact I’m typing this shows it worked but still, rather a harsh life lesson when it comes down to it.

I’m making an assumption here that Duke’s stand-in, Chuck Roberson, doubled for the horse-breaking scenes and the knife fight between Wayne and the Apache warrior Silva, played by Rodolfo Acosta. If that’s the case then it’s good to see Roberson getting his own close-up as a cavalry soldier in the battle at the end of the film. Admittedly it’s a fairly short close-up what with Roberson getting killed a few seconds later but a nice gesture just the same. On the whole a good solid Western in which Wayne turns in what has over the years become quite an iconic role for him, up there with Ethan Edwards and Sean Thornton in terms of popularity. Shame about the dog though.

Admittedly it’s a fairly short close-up what with Roberson getting killed a few seconds later but a nice gesture just the same. On the whole a good solid Western in which Wayne turns in what has over the years become quite an iconic role for him, up there with Ethan Edwards and Sean Thornton in terms of popularity. Shame about the dog though.

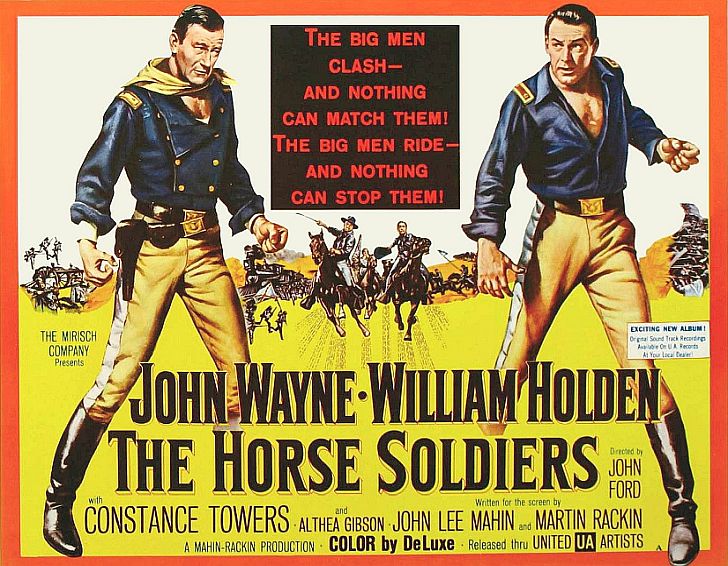

The Horse Soldiers (1959)

Not every John Wayne / John Ford opus, irrespective of genre, has both director and actor firing on all cylinders and The Horse Soldiers unfortunately falls into that category.

On the surface it has all the ingredients for the making of a good film. There’s Wayne working with Ford for the first time since The Searchers, and the established Hollywood actor, William Holden, more than capable of holding his own on the screen with his co-star.

On top of that the subject matter of the story takes place during the American Civil War, a subject that Ford, as an accomplished screen historian, was more than at home with. What could go wrong?

First of all, the chemistry between Wayne and Holden never really comes to life, a bit like Wayne with Robert Ryan in The Flying Leathernecks. They do end up squaring off at each other at some point in the film but their encounter doesn’t posses the pugilistic essence of Wayne’s fisticuffs with other actors such as Forrest Tucker in Chisum or Victor McLaglen in The Quiet Man.

The story is also lacking in real tension and drama, the climax for example being just a case of the Union soldiers, lead by Wayne as, riding across a bridge then blowing it up before the Confederate army catches up with them.

I think the best part of the film is the sequence in which, based upon a true incident, a bunch of young Confederate cadets, some of them still literally children, leave their military academy and march into battle against the Union army. It’s yet another example as to how Ford smuggles relatively unknown American historical events into his films, informing as well as attempting to entertain his audience.

One of the reasons The Horse Soldiers never really kicks into life has been put down to the fact that one of the stuntmen was killed during production of the film.

After that incident is has been recorded by a number of writers on Ford that he lost enthusiasm for the whole thing, as the end result would appear to attest to. Which is kind of a shame when you consider that Ford’s contribution to the Cinerama epic How the West Was Won, filmed a couple of years later, is by far the best sequence in the film, dealing with the savagery and futility of the Civil War itself.

I have a vinyl album from back in the early 1960s which contains a collection of re-recorded and original soundtrack music from films of the era, including the love theme from The Horse Soldiers.

The album indicates that the music is by the soundtrack composer for the film, David Buttolph, but it’s actually a recycling of Martha’s theme from The Searchers, which is itself based upon a traditional piece of music called Loreena. Was this theme used again because Ford simply liked the tune, or indicative of a lack of enthusiasm on the director’s part to oversee the finished result? Answers on a postcard please.

North to Alaska (1960)

I have a confession to make. I wasn’t going to write about this film as I personally didn’t consider it to be a John Wayne Western. When I checked it out online however, the film is listed as a Comedy Western.Unfortunately, this film doesn’t really count as one or the other.

It takes place in 1900 for a start, so we’re not exactly in the classic Western timeline of the mid to late 19th century. On top of that I didn’t laugh once, even when someone punched Wayne and he pulled a funny face to indicate to the audience that they’re supposed to be watching a comedy.

Seeing as this is the part of Duke’s career when filmmakers try to get down with the kids and shoe-horn a teenage singing heartthrob into the action – Ricky Nelson in Rio Bravo and Frankie Avalon in The Alamo, it comes as no surprise to see that great thespian of the silver screen, Fabian, co-starring alongside Wayne, Stewart Granger and the French actress Capucine, who has also obviously decided to drop her surname as well.

The only funny thing about the film is Fabian’s quiff, which seems to have been cemented to the front of his head, stubbornly maintaining its shape despite numerous punches to Fabian’s face whilst rolling around in the mud.

It’s a shame really because Wayne’s other films with director Henry Hathaway such as The Sons of Katie Elder and of course True Grit are real genuine classic Duke Westerns.

This is not one of them so I’m not going to write about it any more. This means I now have a get-out clause when it comes to another Wayne / Hathaway so-called Western, Circus World (aka The Magnificent Showman) because it makes North to Alaska look like Citizen Kane. If such a thing is possible.

You asked what year RIO BRAVO was released and that WAS 1959 – then you spoke about RIO GRANDE which is an entirely DIFFERENT MOVIE

Mary, we asked what year Rio Bravo was made and yes Rio Grande was another movie

but “According to McBride the original title was dropped due to someone making a legal claim on the name, so instead of Rio Bravo we get Rio Grande instead.”