Welcome to the second part of our article on the films John Wayne starred in for celebrated director John Ford. You can catch up with Part I of John Wayne & John Ford movies.

They Were Expendable (1946)

They Were Expendable (1946)

Despite John Wayne being cast second in the bill to Robert Montgomery, this is the first real classic WWII film of his career.

It doesn’t hurt of course that it was directed by John Ford and the film is to our mind an underrated masterpiece in the director’s body of work.

The film tells the story, based on fact, of two navy Lieutenants, John Brickley, played by Montgomery, and Rusty Ryan (Wayne) who are instrumental in utilising PT boats to attack the Japanese navy in defence of the Philippines.

The film itself, like Wayne’s performance, is a subdued and somewhat melancholy affair, bearing in mind, as the screenwriter Lem Dobbs points out in a documentary on Ford, that the title suggests most of the characters are dead by the time their story is told.

There’s a wonderfully understated romantic sequence in which it is obvious both Donna Reed as an army nurse, Sandy, and Rusty have feelings for each other.

Sandy is invited to dine with Rusty and five of his fellow navy comrades, with her being the guest of honour. As the evening draws to a close the couple are left alone, their silent reverie broken by the arrival of the cook who clears the table then thoughtfully blows out the candles on the table, heightening the unspoken intimacy between the two of them.

Rusty finally gets to put his arm around her after which they walk out towards the open porch where Sandy starts to cry, for the men she’s just met and because deep down she and Rusty both know the war isn’t going to allow them a happy ending.

Montgomery had actually served during the war in the Navy and commanded a PT boat in the Pacific. On top of that Ford had also seen action with his photographic unit at Midway, in which he was mildly wounded by some shrapnel, and had also witnessed the D-Day landings.

Ford apparently rode Wayne mercilessly for not having voluntarily enlisted himself, moving Montgomery to intervene on Wayne’s behalf and upbraiding Ford accordingly, which goes some way to explaining Wayne’s low-key performance in the film.

Ford isn’t generally known for his action sequences, being more interested in character and mood. The battle between the PT boats and the Japanese fleet, however, is genuinely exciting and extremely authentic, no doubt helped by Ford and Montgomery having witnessed the real thing during the war itself.

Wayne gets to survive this one, both he and Montgomery having to leave their men behind to help organise other PT boat missions on behalf of the navy.

In keeping with the rest of the film, the ending is somewhat muted, the histrionics kept to a minimum as Wayne tries to stay with his men but Montgomery ordering him to leave, asking the question “who do you work for?”.

Inevitably, this being a WWII movie, the film ends with a rendition of “Glory glory hallelujah”, but the triumphalism is weighed down by the fact that the men they leave behind will most probably not make it back to their families in America.

Fort Apache (1948)

Fort Apache (1948)

The journalist-turned-director Peter Bogdanovich once wrote that if one viewed the films of John Ford in terms of chronological narrative i.e. start with “Drums Along the Mohawk” which is set during the American War of Independence then move on to the Civil War with “The Horse Soldiers” and the settling of the West with “Wagonmaster” etc, the audience would be presented with a fairly comprehensive lesson on the history of America.

Based on that premise, if you want to know what happened to General Custer, look no further than “Fort Apache”. Wayne’s first Western with Ford since “Stagecoach” nearly a decade before, and the first in the director’s unofficial cavalry trilogy, it tells the story of a strait-laced career officer, Lt Col Owen Thursday, played by Henry Fonda, who takes command of the outpost where Wayne, as Captain Kirby Yorke, is also stationed.

Fonda’s character leads his men to a glorious but meaningless death a la Custer at the end of the film, leaving Wayne, who has missed out on the action due to insubordination, to deliver the eulogy for the dead men.

Although Fonda is ostensibly the main star of the film this is where Wayne takes up the baton as Ford’s leading man from now on, Fonda appearing only once more in a Ford film with the troubled production “Mister Roberts” in 1955.

Wayne’s final speech, and his best moment in the film, praises the actions of Thursday and his men, calling to mind the line from the later “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” that, when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

“Fort Apache” sees Wayne working for the first time with Victor McLaglen, here playing Sergeant Mulcahey. Ford stock company perennials Ward Bond and Hank Worden also feature, making this and the other two entries in the trilogy a real family affair. Keep an eye out for other Ford regulars including Anna Lee and Jack Pennick.

It’s worth also noting that from here-on in, Ford’s cinematic depiction of Native Americans begins to evolve from the nameless ciphers as shown in films such as “Stagecoach” to presenting the noble savage as a fully-rounded character with the ability to speak for themselves.

In “Fort Apache”, the real-life Apache chief Cochise gets a fair shake for once, willing to walk the path of peace until Lt Thursday’s by-the-book arrogance forces Cochise to go to war.

In the process, Thursday and his men are wiped out to a man, with Kirby having to paper over doubts about his former commanders do or die attitude in order to preserve the dignity of the military.

It would have helped if Cochise had actually been played by a real Native American as opposed to Mexican actor Miguel Inclan, but it’s a start and the beginning of a cinematic journey for Ford that would result in his last Western, “Cheyenne Autumn”, serving as a personal apology on behalf of the director for the manner in which Hollywood nearly always portrayed America’s indigenous population as the bad guys.

Stagecoach (1939)

“Stagecoach” has everything you would want in a Western – John Wayne, Apaches on the warpath, a drunk doctor (who still manages to deliver a baby without dropping it), a gunfight, a lady of the night, a card sharp, charging cavalry, a stagecoach even – and to top it off, Monument Valley in all its glory.

I could write an article purely on the magic that is Monument Valley but maybe that can keep for another time. Suffice to say that the film is up there in the pantheon of classic Hollywood Westerns along with “Shane”, “The Searchers”, “Red River”, “High Noon” and “The Wild Bunch”.

The icing on the cake is that not only did it finally make Wayne a star but it helped elevate the Western back to its deserved status as a major Hollywood genre.

The year 1939 wasn’t exactly starved of classic Western fare, there being “Dodge City”, “Jesse James” and even Ford’s own “Drums Along the Mohawk” to contend with, but “Stagecoach” comes top of the list for that year.

Bearing in mind John Ford is known mainly for his Westerns this was the first time he had directed in this genre since the silent days, the last Western he made previously to “Stagecoach” being “Three Bad Men” back in 1926.

It’s fair to say that he set the bar for the cowboy films that followed with Wayne eventually graduating to being an essential ingredient of major ‘A’ status Westerns.

Although he was second on the bill to Claire Trevor, who plays Dallas, a prostitute with a heart of gold, the film revolves mainly around his character, the Ringo Kid, and his determination to avenge the death of his brother at the hands of the Plummer gang.

You could argue that the whole story of the stagecoach chase and ultimate rescue by the cavalry is a mere anti-climax to the final shootout between Ringo and his brother’s killers.

It’s almost two films rolled into one and Ford keeps the action moving from the minute the stagecoach leaves for Lordsburg.

Wayne is still in his innocent cowboy phase, good with a gun but naïve and inexperienced when it comes to the female sex. On the other hand, no one watches a Wayne film for the romantic content, “The Quiet Man” being an exception, but to see the big man in action with guns a-blazing, and “Stagecoach” has more than enough of that to please even the most casual viewer.

It also helped that JW found himself in the middle of a great ensemble cast. Apart from Claire Trevor, able support is provided courtesy of Thomas Mitchell, winning a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role as the alcoholic Doc Boone, as well as John Carradine as a cheating Southern card-sharp and Andy Devine as Buck, the stagecoach driver.

The Academy Award winning soundtrack by Richard Hagen is definitely worth tracking down too if you get the chance, as it features a great collection of original “pioneer” songs such as “Shall We Gather at the River?” and “Don’t Bury Me on the Lone Prairie”.

The movie may be over seventy years old but it still retains the ability to thrill and engage audiences who weren’t even a twinkle in their parent’s eye when it was first released.

It’s a great beginning to a Western partnership between Wayne and Ford that only got better as time went on, and a bona fide Hollywood classic that should be required viewing for John Wayne fans of all ages.

Avoid the 1966 remake at all costs.

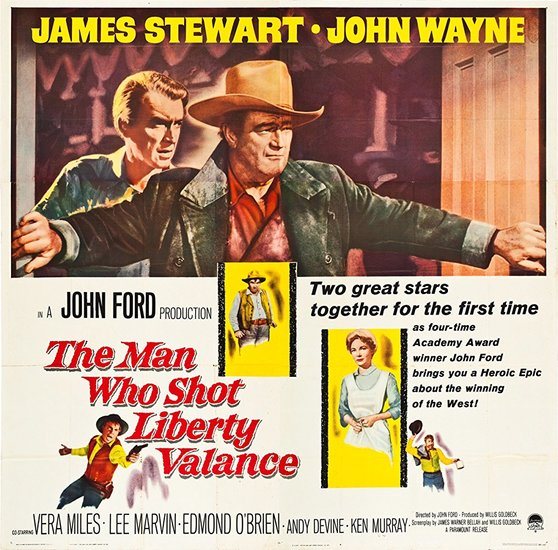

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

The last Western film partnership between Wayne and John Ford and Ford’s penultimate Western, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” is itself shot through with so many of the director’s familiar thematic motifs it’s difficult to know where to begin.

Just for starters how about East versus West in terms of rancher Tom Doniphon, played by Wayne, and fancy idealistic lawyer Ransom Stoddard, played by James Stewart.

There’s also the issue of civilisation versus savagery, particularly early on when Stoddard is given a good stomping by Valance himself, here played with vicious relish by Lee Marvin at his psychopathic best.

Doniphon’s disdain of Stoddard, who comes to threaten his relationship with Hallie, played by Vera Miles, is indicated by his continually referring to the lawyer as ‘Pilgrim’, a term not necessarily one of endearment.

The film is told in flashback after Stoddard and Hallie, now his wife, visit the town of Shinbone to pay their respects at Doniphon’s funeral.

It starts to become obvious almost from the beginning that the pivotal character in the story isn’t Stoddard or Doniphon, or Valance for that matter.

It’s Hallie and the manner in which her attention slowly turns from the rancher to the lawyer.

Narrative analysis aside, Ford assembles a great cast of character actors to bolster the action, including Strother Martin and Lee van Cleef as a couple of Valance acolytes, Edmond O’Brien as crusading newspaperman (is there ever any other kind?), Dutton Peabody, Woody Strode as Doniphon’s faithful manservant Pompey and vintage Ford stock company actors including John Carradine and Andy Devine, the latter making quite a good impression as the redundant sheriff of Shinbone, Link Appleyard.

The film builds steadily towards the inevitable confrontation between Stoddard and Valance, both of them facing off against each other at night in the dimly lit main street of the town, with the lawyer apparently getting off a lucky shot and dispatching Valance in the process.

There’s then another flashback within a flashback when later on, after Stoddard has doubted whether he should attempt to be nominated to a Washington delegation assigned to lobby for statehood on the back of his reputation as the man who shot Liberty Valance, learns from Doniphon that it was he, and not Stoddard, who actually did the shooting, as illustrated in yet another flashback.

The upshot of all this is that Stoddard gets the girl and eventually becomes a senator, whilst Doniphon is left by the wayside, burning down the house he had built in anticipation of marrying Hallie, now lost to the Eastern interloper.

Coming back to the present, Stoddard tells the real story to a newspaper reporter, played by Carleton Young, who disposes of his notes with the comment, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”.

Ford keeps the final reveal right until the end when Stoddard notices a cactus rose placed atop Doniphon’s casket. On the train journey out of Shinbone Stoddard asks Hallie if she was the one that left it there to which she replies it was indeed her.

Only then does Stoddard finally realise that, although Hallie gave herself to him, it was Doniphon whom she really loved all along, a suggestion reinforced when she also reacts positively to his suggestion that one day they might settle back in Shinbone.

It’s a typically unhappy Ford ending, much like that of “The Searchers” when Ethan Edwards is left outside the cabin after having helped reunite Debbie and her relatives, no longer needed and left to wander with the wind on his own.

This is definitely both Ford’s last great Western and his last great film, with Duke yet again showing what a good actor he could be when he didn’t necessarily have to play John Wayne all the time.

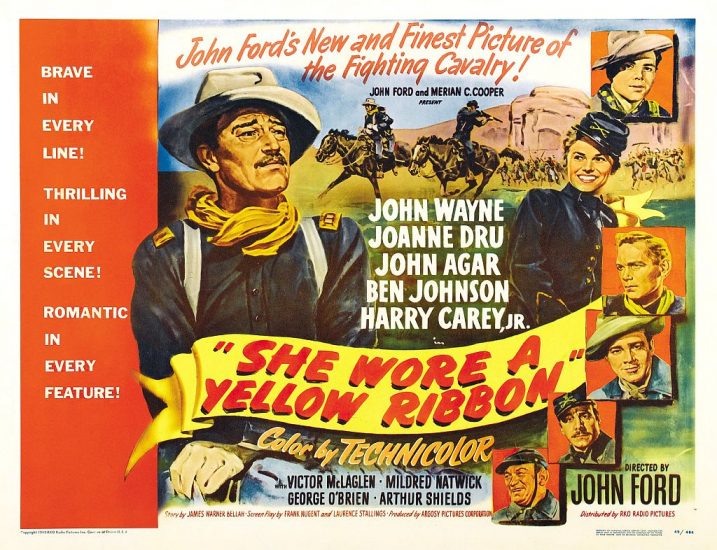

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)

If anyone has any doubts about John Wayne’s acting ability, his performance as Captain Nathan Brittles should convince otherwise.

Playing a character older than the actor was at the time, Wayne is utterly convincing as the elderly soldier called upon to perform one last mission to help negotiate peace between the warring Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes before heading off to retirement.

This is less an action film and more a rumination on growing old, the scene towards the end of the film when he and Chief Pony That Walks discuss going hunting, fishing and drinking reinforcing the anachronistic nature of the two characters.

For some strange reason, Wayne seemed to think when he was interviewed in 1971 for Playboy that he had been nominated for an Oscar for this film. Unfortunately, that turns out not to be the case but he was definitely robbed in our opinion, delivering a more studied and measured performance here than he did in “Sands of Iwo Jima” which was released in the same year, for which he did actually receive his first Academy nomination.

It’s the last and best of Ford’s cavalry trilogy, bolstered by a sterling contingent of his stock acting team including Mildred Natwick, Arthur Shields, Ben Johnson and George O’Brien.

Ford veteran Victor McLaglen is also along for the ride as Sergeant Quincannon, an Irishman fond of the drink who is also on the cusp of retiring.

There is a bit of a clunky love triangle sub-plot featuring Joanne Dru, Harry Carey Jr. and John Agar that detracts from the main story of Wayne’s impending retirement. That’s a small price to pay though when matched against his bittersweet acting, particularly the scene where his troop presents him with a gold watch ‘with a sentiment on the back’.

Prior to “The Searchers”, Monument Valley has never looked so beautiful and the Oscar winning cinematography of Winton Hoch captures the landscape like never before. Add to that the peerless direction of John Ford and you have a perfect example of how Ford and Wayne can deliver the goods when they’re both firing on all cylinders.

It’s in colour too.

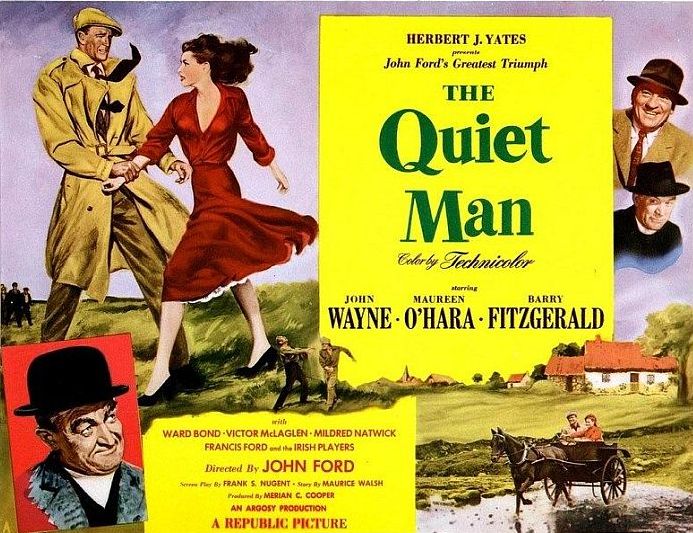

The Quiet Man (1952)

The Quiet Man (1952)

After “The Searchers”, this is, without doubt, the second most popular cinematic outing for the Wayne / John Ford partnership.

It had been a cherished project of Ford’s for a long time but the only way he could get the financing off the ground was to make a Western for Republic studio head Herbert Yates.

Ford delivered “Rio Grande”, which paired Wayne with his future “Quiet Man” co-star Maureen O’Hara for the first time, and the box-office take was enough to persuade Yates to grudgingly cough up the production money for the director’s Irish film.

The film is very loosely based around a series of short stories written by Irish author Maurice Walsh and published together in a book originally called “The Green Rushes”.

One of the stories, entitled “The Quiet Man”, revolves around Paddy Bawn Enright, who leaves for America at the age of 17 and boxes under the name of Tiger Enright for a few years before returning to Ireland at the age of 32.

He joins the IRA Flying Column under the leadership of Mickeen Og Flynn, before romancing and marrying the red-haired Ellen Roe O’Danaher, younger sister of local thug Red Will O’Danaher, the man who had filched Enright’s family home whilst Enright was in the States.

From this material, Ford and scriptwriter Frank Nugent forged the screen story of “The Quiet Man”, with Paddy Brawn rechristened as Sean ‘Trooper’ Thornton, and Ellen Roe as Mary Kate, some Ford scholars maintaining Mary was in reference to Ford’s wife and Kate after Katherine Hepburn with whom the director was rumoured to have had an affair.

The end result turned out to be a Hollywood perennial classic that plays on TV on a regular basis and was one of Ford’s biggest box-office hits in his 50-year directing career. On top of that, it garnered the director his fourth best directing Oscar, a feat still unbeaten by any other film-maker.

We’re not going to recount the story of the film here as the assumption is that any JW fan worth their salt knows the movie backward.

Suffice to say that Duke acquits himself well, successfully capturing the angst of an ex-boxer who has accidentally killed a man in the ring back in America, and just happy to live a quiet life as a quiet man in the country of his birth.

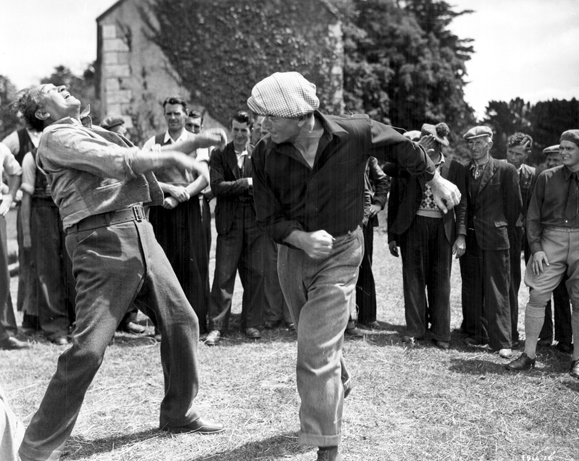

The highlights are numerous, particularly the much-anticipated fistfight between Wayne and Victor ‘Red Will’ McLaglen which is as climactic as any gun-fighting face-off from any Western you’d care to name.

The highlights are numerous, particularly the much-anticipated fistfight between Wayne and Victor ‘Red Will’ McLaglen which is as climactic as any gun-fighting face-off from any Western you’d care to name.

Over the years “The Quiet Man” has become one of those movies you either love or hate.

Detractors of the film point to specific aspects of the film that in this day are considered outdated, particularly as regards its attitude towards women and the stereotypical nature of a lot of the supporting characters.

However, this fails to diminish in any way the power of the story nor the breath-taking beauty of the Irish country-side, the exterior sequences having been shot on location in and around the village of Cong in County Mayo.

Add to that the ‘illegally beautiful’ Maureen O’Hara and you have yourself a cinematic offering that only the most cynical viewer would not enjoy.

The film is the closest that Ford ever came to making a full-blown musical, an Irish “Brigadoon” if you like.

Everyone in the film seems to want to exercise their tonsils at the drop of a hat, with renditions of classic Irish evergreens such as “The Wild Colonial Boy”, “Galway Bay” and “The Humour is on Me Now” scattered throughout the movie.

The film itself is a Hollywood depiction of Ireland that’s so ‘Oirish’ you half expect to see a leprechaun emerge from behind the scenery at any given moment, then Barry Fitzgerald appears and if he isn’t a leprechaun in spirit as well as demeanour we’ll eat our green St. Patrick’s Guinness hats.

So watch, enjoy, and like thousands of others before you try and figure out what exactly it is that Maureen O’Hara whispers in Wayne’s ear right at the end of the film.

By the look on his face, I’m guessing it’s not something you’d say out loud in front of the kids.

The Searchers (1956)

The Searchers (1956)

“The Searchers” is definitely the best of the Westerns that John Wayne made with director John Ford, and to most JW fans the best film the two of them made together, the movie growing in stature over the years to the point where it now regularly makes it into the top ten list of greatest films ever made.

The centrepiece of “The Searchers” is the magnificent portrayal by John Wayne of the embittered Ethan Edwards, returning to his brother’s home after having fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Anyone expecting to see the steadfast, upright, morally correct individual that Wayne’s screen persona is usually associated with is going to be severely disappointed.

I can’t think of any other Wayne film made either before or after “The Searchers” in which he shoots three men in the back, blasts out the eyes of a dead Comanche warrior, mutilates the corpse of the dead Comanche chief Scar, and attempts to murder one of his own relatives.

He’s a snarling, angry, bigoted racist who wants to put a bullet into the brain of his niece, Debbie because she had the misfortune to be kidnapped and thus tainted by association with the Comanche tribe that took her away.

She is no longer acceptable in white society so has to be eliminated and Ethan Edwards is up for the job, which is what makes “The Searchers” unique in John Wayne’s acting resume.

As for Ford, one of the aspects of “The Searchers” worth noting is the manner in which he continues to depict his Native American characters in a more positive light, in this case, the Comanche woman Look, and a continuation of the turning point in “Fort Apache” when the director’s onscreen attitude towards America’s indigenous natives became more sympathetic.

Some of the images from the sequence in which Ethan Edwards and Martin Pawley chance upon the corpse of Look in a Comanche village devastated by the cavalry bears comparison with some of the late 60s / early 70s liberal Westerns such as “Soldier Blue” and “Little Big Man”.

This film also finds John Ford questioning the role of the military in the ‘settling’ of the West and he doesn’t pull any punches.

The cavalry regiment that arrives in the nick of time at the end of “Stagecoach”, flags flying gloriously in the wind, is now transformed into a ruthless band of cutthroats who kill in the name of Manifest Destiny, and it’s up there on the big screen for all to see.

The Native Americans in “The Searchers” and in Ford’s last Western, “Cheyenne Autumn”, are no longer depicted as ciphers or silhouettes on the horizon. They are shown as real people with real lives and emotions, the characters in the film elevated in the storyline and sharing equal screen time with the white protagonists.

On a different note, the magnificence of Monument Valley is shown probably at its best in “The Searchers”. The silhouettes of the towering buttes and the dark orange of the desert have come to personify the cowboy film over the years since Ford first went there in the late 1930s to film “Stagecoach”, the director single-handedly developing a cinematic shorthand for depicting the West.

The landscape hides the marauding Native Americans just before they snake along the slopes surrounding Ethan and his search party.

The valley then reduces the size of the individuals in pursuit of Debbie until they are rendered almost invisible to the naked eye by a backdrop that has not changed in millions of years, and will remain in place long after Ethan and his compatriots have turned to dust.

Ford’s direction perfectly encapsulates the isolation and unforgiving savagery of the wilderness as exemplified by the location itself.

There are so many special moments to celebrate that will forever stay in the memory of those who revere “The Searchers”, and would take quite a while to list, but here’s a few to be going on with

- Ethan’s sister-in-law, Martha, emerging from the cabin at the opening of the film into the bright sunlight just as he appears riding out of the magnificent landscape of Monument valley

- the wonderfully understated moment when Ward Bond as the Reverend Clayton pretends to ignore the obvious feelings that Ethan and Martha have for each other

- the look of sorrow on Ethan’s face when he realises later on that he won’t get back in time to save his brother’s family from an Indian attack

- the marauding Comanches suddenly emerging from the landscape as they snake along the slopes of the valley surrounding Ethan and the search party

- the look of pure contempt suffused with pity on Ethan’s face for the white captive of the Comanches who mistakes a doll for her dead child

- the iconic moment when Ethan lifts Debbie high into the air then tells her, “let’s go home Debbie”, a scene that still makes the hair stand up on the back of the neck no matter how many times it is viewed

- and finally, the lone figure of Ethan standing in the cabin doorway as Debbie is welcomed back into the fold, Wayne holding his right arm in homage to actor Harry Carey Sr. before walking away in search of heart and soul as the cabin door closes behind him.

The film has influenced numerous other directors such as Martin Scorsese, Paul Schraeder and Steven Spielberg. George Lucas appropriated part of the story for the first Star Wars film – John Wayne’s character Ethan Edwards (Hans Solo) helps a young man, Marty, played by Jeffrey Hunter (Luke Skywalker) to go looking for Marty’s half-sister Debbie (Princess Leia) who has been kidnapped by the cruel Comanche warrior Scar (Darth Vader).

In “Attack of the Clones” Lucas even recreates shot-for-shot the scene towards the end of “The Searchers” in which Marty rescues Debbie from the clutches of Scar.

There also aren’t many other films that can lay claim to have inspired a number one hit single, Buddy Holly and the Crickets recording “That’ll Be the Day” after seeing the film and taking note of Ethan’s catchphrase.

With a wonderful supporting cast of Ford stock company actors including John Qualen, Harry Carey Jr., Ken Curtis and Hank Worden as the simple-minded Mose, “The Searchers” is a triumph for all concerned.

When it comes to either the films of John Wayne, or the films of John Ford, or the Western genre in particular, it truly does not get any better than this.