Welcome to part one of our two-part article on the best of John Wayne’s pre-stardom Westerns.

Having spent quite a lot of time reviewing the films John Wayne appeared in before stardom beckoned with “Stagecoach” I thought I’d go back and pick my top ten Westerns from what I call his ‘wilderness’ years.

This is purely a personal preference but hopefully, you’ll find some of your own favourites in the list of films featured in this article.

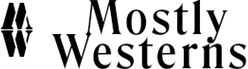

The New Frontier (1935) Republic, Dir: Carl L. Pierson, b/w, 54m

Cast: John Wayne, Muriel Evans, Warner Richmond, Alan Bridge, Sam Flint, Murdock MacQuarrie

“The New Frontier” should not be confused with the later 1939 JW / Republic vehicle “New Frontier”, which was retitled “Frontier Horizon”. Glad we can clear that one up. Read on, pardners.

Released in October 1935, this is the second in the series of sixteen low-budget Westerns John Wayne starred in for Republic Studios. Set in 1889, the story begins with the President of the USA Benjamin Harrison signing off on a land grab whereby the white settlers can lawfully steal large swathes of America from the indigenous natives in the name of Manifest Destiny.

From this land grab arises a new town on the new frontier in a town imaginatively christened as Frontier. The place turns out to be in need of someone capable of bringing law and order to the streets so who do you reckon the townsfolk call on to be the new sheriff?

That’s right –Milt Dawson (Sam Flint), the man who helped lead the first wagon train that brought the people who then built the new town of Frontier and who also happens to be the father of JWs character, John Dawson.

Milt wisely turns the job down, then unwisely decides to tell the local villain, Ace Holmes (Warner Richmond), to keep the noise down anyway.

Milt doesn’t even get to make it out of Ace’s saloon before he succumbs to a serious case of lead poisoning, administered in the back by a murderin’ varmint of dubious parentage.

Meanwhile, Milt’s son is leading a wagon train of more settlers to Frontier.

On the way, they’re attacked by a group of outlaws looking for food. When the leader of the gang, Kit (Al Bridge), realizes that John Dawson is the lead scout for the wagon train, he offers to pay for the food instead, on account of John having helped him out when Kit was wounded some years before.

When the wagons finally hit town John finds out he’s now an orphan so takes on the role of sheriff in order to get the gutter trash that done killed his pa.

He then confronts Ace in the saloon, both of them treated to a couple of closeups more in keeping with a Sergio Leone film, with John looking like he’s out for trouble, and Ace sure looking like he’s going to oblige. John tells Ace to close his saloon by six, otherwise, he’s destined for the hoosegow.

Instead of shooting him in the back like he did John’s pa, dastardly Al sets the new sheriff up by luring him to meet a stranger who offers to give up the name of his pa’s killer.

Realising he’s been tricked, John gets the drop on one of the gang who was threatening to drygulch him, then sends him on his horse towards the killers lying in wait.

They then shoot their own man, echoing a similar scene from the much later “Rio Bravo”, demonstrating yet again how much directors like Howard Hawks weren’t afraid to recycle ideas from older films.

John then confronts Ace once more in the saloon and gets thumped over the head for his troubles. Just as Ace is about to finish him off, that nice outlaw guy Kit turns up and saves the day.

In what turns out to be quite a spectacular climax, the opposing forces shoot it out with each other and end up burning down most of the town in the process.

Apart from a couple of funereal dirges interpolated into the action in the style of the Singing Riders from “Westward Ho”, and an inconsequential leading lady played by Muriel Evans, I’d say there’s definitely more action to be had than in previous JW Westerns, which augured well for his move to Republic.

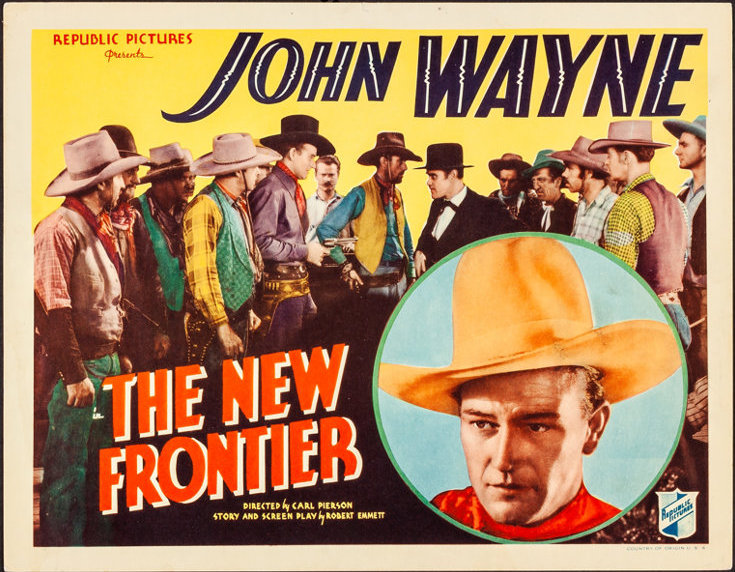

Blue Steel (1934) Lone Star, Dir: Robert N. Bradbury, b/w, 54m

Cast: John Wayne, Eleanor Hunt, George Hayes, Edward Peil, Yakima Canutt, Lafe McKee

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that a few of the early Westerns John Wayne appeared in with Gabby Hayes make it onto this list, seeing as they co-starred in fifteen films altogether.

This one, released in May 1934, is the third film in a screen partnership that ran for just over a decade.

Someone’s goofed.

George “Gabby” Hayes has been made the sheriff.

On top of that, the Gabby persona is now really starting to kick in – big time. His mouth seems to be permanently chewing down on the old tobacco and his pronunciation is now almost pure FG – that’s frontier gibberish to any of you newcomers out there.

And he’s now, at the grand old age of forty-nine, officially an “old-timer”.

The film starts with a creepy looking newlywed on his honeymoon appearing in reception to tell the clerk that he “can’t find it”.

The audience is left to surmise that he’s talking about the water closet but, just to raise the double entendre bar slightly higher, it looks suspiciously as though the sheriff and the desk clerk share a room together.

Duke, here playing an undercover Marshall by the name of John Carruthers, has snuck into the hotel while no one’s looking and taken up residence in what looks like a closet with a very small bed in it just off the reception area.

Hearing a noise, he awakes and witnesses a thief stealing four thousand dollars from the hotel safe, the robber leaving behind a broken spur as a clue.

Moments later, Sheriff Jake Withers espies John through a hole in the floor of his room in front of the safe and draws the wrong conclusion, declaring “By jiminy – it’s the polky dot”, which is Gabby talk for “The Polka Dot Bandit”, and it soon becomes clear John is not exactly on the level.

This is because “Blue Steel” is yet another of those ‘let’s send a letter to the government to get someone down here to sort out this constant banditry / land-grabbing / rustling / etc. – oh hang on a minute he’s already here and goshdarn don’t he look like that John Wayne feller.’

As another review of this points out, there’s a tendency in these low-budget cowboys films to have characters spout aloud on their plans without checking that no one’s listening.

In this case, love interest Betty Mason (Eleanor Hunt), overhears villains Malgrove (Edward Pell) and Danti (Yakima Canutt) spilling the beans on their dirty plan to buy out the homesteaders and trick them out of a fortune in gold that the owners are unaware lays right beneath the surface.

John and the sheriff inevitably join forces and for some reason decide to go shopping whereupon the old-timer finds himself a box of “dyneemite” – holy Walter Brennan. Eventually good triumphs over bad and the villains get their comeuppance.

This time round though, there’s no horse chase ending with JW handing out a whupping before turning the bad guy over to the law, nor a prolonged shootout in which Duke is then morally obliged to gun the main villain down like the mangy dog he is. No.

This time they just blow the whole gang to smithereens in a canyon. Not exactly subtle, but it makes a nice change from the aforementioned options.

Although the film brings nothing new in terms of plot or characterization, the spectacular scenery captured in the location shots at Big Pine help to elevate “Blue Steel” in comparison to some of the other tired entries in the Lone Star series of JW films.

It’s almost as though someone has made an attempt to improve the look and feel of the film, and the movie is better for it, introducing a whole new element to the series.

Winds of the Wasteland (1936) Republic, Dir: Mack V. Wright, b/w, 55m

Cast: John Wayne, Phyllis Fraser, Lew Kelly, Douglas Cosgrove, Lane Chandler, Sam Flint

Just like “The Lonely Trail”, the film John Wayne starred in for Republic prior to this, “Winds of the Wasteland”, released in June 1936 and the eighth oater JW appeared in for the studio, this also takes its cue from the history of the Old West, in this case, the demise of the Pony Express, which ceased running in 1861.

JW plays ex-Pony Express rider John Blair who, along with his fellow out-of-work companion Larry Adams (Lane Chandler), decides to set up their own stage line business.

Off they ride to Buchanan City in order to procure themselves a stagecoach to tether to the four horses the two friends received in redundancy pay from their previous job.

They approach the owner of the local stagecoach service, Cal Drake (Douglas Cosgrove), who persuades them instead to invest in one of his franchises, which runs to a place called Crescent City.

And it’s only going to cost Blair and Adams a paltry three-thousand dollars, one-thousand in cash and two extra payments of one-thousand dollars once the boys have got their stage business up and running.

Knowing a bargain when they see one, the hapless partners sign a deal with Drake, hand over their payoff money and travel down to Crescent City, only to discover they’ve been sold a pup on account of the place being a ghost town.

Instead of riding straight back to Buchanan City and forcing the swindler to give them back their money at the point of a gun, they decide to stay on and make a go of it.

They meet the only two residents left in the town of Crescent City, Rocky O’Brien (Luke Kelly), and Doc Forsythe,( Sam Flint).

Rocky informs John that a mail contract worth twenty-five thousand dollars is up for grabs to run between Buchanan City and Sacramento, the contract being awarded to whoever drives the fastest stagecoach between the two towns.

The tone of the film is defined by the light-hearted background music that would be more at home on the soundtrack to a Laurel and Hardy comedy as opposed to a Western, leaving the audience in no doubt that it’s not exactly a film to be taken too seriously. T

his comedic aspect is compounded when they find a skunk in the old stagecoach at Crescent City that Drake sold to them, everyone concerned running a mile to get away from it as quickly as possible.

Duke even gets to crack a joke, commenting when confronted by one of Drake’s bad guys on arriving back at Buchanan City that “I didn’t know school let out so early”.

At this point, entering literally from stage right on a stagecoach, who should turn up but Doc Forsythe’s attractive daughter Barbara (Phyllis Fraser), who is suitably underwhelmed when she then hops on John and Larry’s stagecoach to see her father in Crescent City and catches sight of the abandoned town.

To make matters worse for villain Drake, John chances upon a telegraph crew who have fallen ill after drinking poisoned water. After saving their lives the grateful boss of the crew offers to run the telegraph lines through Crescent City as opposed to Buchanan, which then puts the duo at odds with Drake.

Seemingly falling for one of Drake’s schemes again, John and Larry agree to deliver some gold bullion to Sacramento, Drake intending to have his men hold up the stage and shoot John in the process.

John plays along with the charade and then outwits his potential killers, delivering the gold successfully and then holding Drake to his promise to cancel the first installment of one-thousand dollars he had agreed to pay for the stage franchise to Crescent City.

The climax to the film is the much-anticipated stagecoach race to Sacramento, the only entries being John versus Drake. The villain pulls out all the stops in order to win but in the end our hero gets the upper hand, the mail contract and of course the girl.

The race itself is genuinely exciting, even though we all know who is going to win. Duke also gets to leap onto the horses at one point just like he does in “Stagecoach” a few years later, then gunning down a couple of Drakes cronies, including stuntman Yakima Canutt, who would double as an Apache chasing Wayne once again in the later Ford classic.

A very good entry in Wayne’s early career at Republic.

Hell Town (aka Born to the West) (1937) Paramount, Dir: Charles Barton, b/w, 55m

Cast: John Wayne, Marsha Hunt, John Mack Brown, John Patterson, Monty Blue, Lucien Littlefield

Released in June 1936, the opening of the film features a spectacular looking landscape with lots of cattle being driven through the wilderness accompanied on the soundtrack by a song that comes across like an earlier version of the theme to “Red River”.

Based on a Zane Gray novel, Duke plays a card-practicing character with the rather strange name of Dare Rudd who, along with his partner, Dink Hooley (Syd Salor), stumble across a bunch of rustlers trying to steal a large herd of cattle.

The footage for this sequence is apparently taken from an earlier silent version of the film, and it’s a bit confusing to say the least, what with Dare and his companion accidentally siding with the rustlers before being apprehended by Tom Fillmore (Johnny Mack Brown), who turns out to be Dare’s cousin.

Seemingly bereft of any kind of family loyalty, Dare starts making eyes at cousin Tom’s gal, Judy (Marsha Hunt), despite knowing Tom is sweet on her.

The real villains of the piece, however, turn out to be Bart Hammond (Monte Blue), and rustler Lynn Hardy, (John Patterson), who attempt to relieve cousin Tom of his ready-for-market cattle, the herd that Hardy had failed to steal at the beginning of the film.

After rescuing Judy when her horse is spooked by a rattler, cousin Tom rewards Dare by giving him the job of herding his cattle, displacing Hardy as Tom’s original trail boss who had intended to steal the cattle at a later date, what with him being in cahoots with bad Bart Hammond.

Hardy lets on to Hammond’s gang of rustlers that they can steal the cattle but Dare has already figured out there’s villainy afoot and tricks the rustlers into thinking the good guys are asleep, driving the varmints off before they’re able to snaffle the herd.

Unfortunately, Dare ain’t as smart as he thinks he is. After safely delivering the cattle and picking up a whole bunch of money ear-marked for cousin Tom, he gets taken in a card game by the “best poker player west of the Mississippi”, and starts to lose the cash big-time.

The sap known as cousin Tom tells Judy he gave Dare the job of herding and selling his cattle in the full knowledge that Dare would show his true colours, which he does by gambling with Tom’s money.

Judy persuades Tom to give Dare another chance so he rides off to fetch his cousin to find him losing ten thousand dollars at poker. Tom steps in, gets most of the money back then foils Hammond’s plans when he realises Dare has been the victim of a rigged game.

This ostensibly makes cousin Tom the real good guy and Dare a bit of a hapless loser. Tom’s reward for this is to be shot before he, Dare and Dink hightail it out of town with the bad guys in pursuit.

Dink rides off to get help from the good guys who have already left town after which Hammond and the other galoots get their just deserts in a shootout at the end.

Cousin Tom, who must have huge self-esteem issues, not only engineers a love match between Dare and Judy, he also offers his wayward cousin a partnership in his company.

Duke was on loan-out to Paramount from Republic on this one and it really shows in terms of Paramount’s more ambitious production values coming to the fore, particularly as regards both the script and the soundtrack, the latter featuring a pleasant instrumental rendering of “Don’t Bury Me on the Lone Prairie “. It also makes quite a refreshing change to see JW playing a bit of a rascal for once as opposed to the morally upright straight talking hero we’ve all come to know and love, and it quite suits him to be honest.

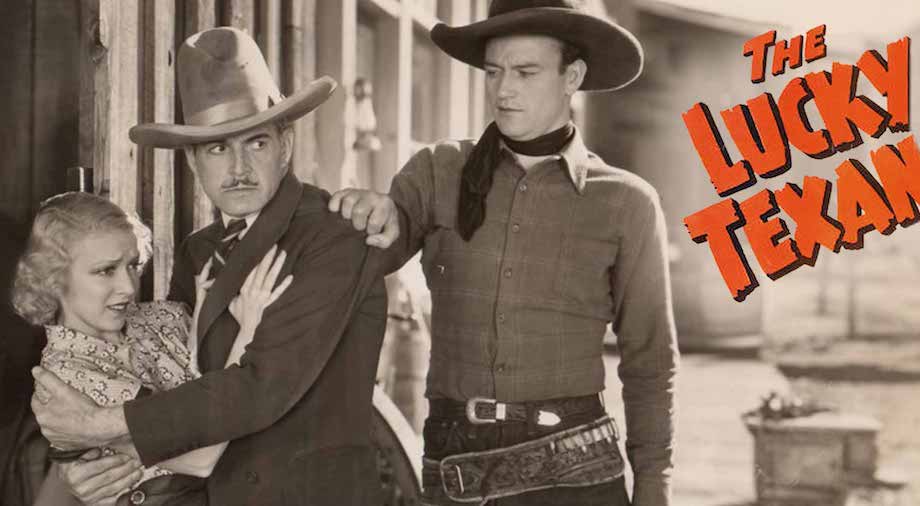

The Lucky Texan (1934) Lone Star, Dir: Robert N. Bradbury, b/w, 54m

Cast: John Wayne, Barbara Sheldon, Lloyd Whitlock, George ‘Gabby’ Hayes, Yakima Canutt, Eddie Parker

A Lone Star production with Wayne and Gabby Hayes partnered together for the eighth time, “The Lucky Texan” has Duke, as Jerry Mason, John Wayne, arriving back in town after college.

He and Gabby (Grandy Benson) discover their shared creek is full of gold and mistakenly reveal their find to a crooked assayer who goes solely by the one word name of Harris (Lloyd Whitlock).

Harris immediately starts figuring out how to take the gold away from Jerry, or “Gabby” Wayne as he should have been called, on account of him telling Harris about the strike without checking first if the essayer was on the square. Which he obviously isn’t.

Naturally, the two partners get swindled, Harris first getting Grandy, or Stupid as he ought to be known, to signing over the deeds to his ranch.

On top of that, not only does Harris short-change Grandy when paying for the gold, he also realises the older man is the gift that just keeps on giving, having previously tried to drive the old galoot out of the cattle business after rustling his herd.

In the meantime, the sheriff’s son, Al Miller (Eddy Parker), who owes mucho dinera to Harris, watches enviously as Grandy compounds his idiotic ways by standing outside the local bank and counting the money he’s made from the gold right in front of Junior’s eyes.

Just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse, Grandy then gets framed for murdering the local banker, only it was Al what really did it when he stole the money Grandy handed over to the murdered man.

There’s an interesting camera technique used by cinematographer Archie Stout that features a couple of times in the film. Whenever JW jumps on his horse and starts galloping away, the camera suddenly tracks either to the left or the right and the scene instantly changes to show he’s arrived at his destination.

I’d like to think it’s an early version of the jump-cut, a visual device championed by French Wave directors such as Jean Luc Godard in the 1950s.

Bearing in mind how cheap these early Wayne movies cost to make though, I’m guessing it’s more of a cost-cutting exercise to save on film. Still, an intriguing thought for all you film studies students out there.

Harris and his sidekick Joe Cole (Yakima Canutt), figure Grandy has bought the farm after they try and wipe him out, but the old man is only wounded.

Grandy tells his faithful dog, Friday, to go and fetch Jerry, which the dog dutifully does. When I then heard Gabby / Grandy tell JW / Jerry to “open up that trunk and get out my makeup kit”, words I thought I’d never actually hear Gabby Hayes ever utter, Jerry produces a full length dress for his friend.

It’s good to know that in the new world of diversity and gender fluidity we now found ourselves living that 1930s Hollywood acknowledged the existence of transgender people in the days of the Old West.

Then it turns out that Grandy used to be an actor. That’s what he reckons anyway.

Somehow or other Jerry is then framed for killing his sidekick and ends up on trial for murder.

Grandy, now dressed as a woman, attends the trial and engages in conversation with Harris and Cole, the men who did actually try to kill him. the men who actually did try to kill him.

Grandy then suggests that the sheriff doesn’t let anyone leave the courtroom as he / she knows who tried to kill the man that Jerry has been framed for murdering.

When Grandy reveals himself as the dead man the two villains leave through the window, thus eluding the sheriff who expected them to leave via the front door.

There then ensues a horse chase with Yakima Canutt doubling as Wayne and ending up chasing himself.

The chase morphs from equine to motorised as Harris and Cole abandon their steeds and try and make a getaway on a small petrol-fuelled railway cart. Grandy joins the chase in a jalopy and, whilst Jerry and Cole duke it out, he engages in fisticuffs with Harris, albeit still half-dressed as a woman.

Oh, and there’s a girl in it as well, and she and Jerry get married.

I really liked this one. It’s a shame there weren’t too many more of JWs 1930 Westerns in the same vein.

Time For A Break

Time for a coffee…

Welcome to part two of our two-part article on what we consider the ten best John Wayne pre-stardom Westerns.

West of the Divide (1934) Lone Star, Dir: Robert N. Bradbury, b/w, 54m

Cast: John Wayne, Virginia Faire Brown, George Hayes, Lloyd Whitlock, Yakima Canutt, Lafe McKee

Although I wasn’t expecting too much from yet another of Duke’s early period oaters, I have to say that on occasion something comes along that really makes you sit up and take notice.

“West of the Divide” is one of those films because I can’t even begin to describe how amazed I was to stumble across a relatively unknown JW death scene that I had not been aware of before. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

George Hayes, playing alongside Duke for, I think, the third time, definitely appears to have been working on his screen persona in between John Wayne movies.

You can see in this film that there’s a real sense that the actor is starting to make his mark.

The constant chewing of tobacco and the perpetual gurning of his unshaven face along with the occasional incomprehensibility of his speech indicate the imminent birth of the one who would forever be known as “Gabby” Hayes. And it all started here.

Duke, playing a character called Ted Hayden, and his trusty sidekick Dusty, played by Hayes, are reclining in the countryside a spell when a stranger appears from out of nowhere muttering that he’s drunk poisoned water.

After the man dies, Duke Ted a wanted poster on the body of the dead guy, who turns out to be a hired gun called Gatt Gans.

Dusty points out that Gans and Hayden look awfully alike so Ted decides to impersonate Gans, who it turns out has been hired by the villain of the piece, a Mr. Gentry, to help run off an old man and his daughter from their ranch.

It then becomes clear why Wayne is dressed in black on account of him taking on the guise of a killer. Not only that but Gatt Gans is actually played by none other than Wayne himself, meaning that we can add yet another film to the list of those movies in which JW cops it.

At some point in the proceedings, Ted finds out that Gentry was the one who shot his pa and also left Ted for dead as well.

On top of that, the AK (annoying kid) who’s actually not that too annoying, probably a maximum of four on an AK scale of one to ten, turns out to be Ted’s little brother. What with Duke playing a ‘villain’, he’s apt to get a little ornery every now and then, telling his little brother’s guardian ‘You ever whip that kid again I’ll break every bone in your carcass.’

This is before he finds out the kid is family. Imagine what he would have done to the guy if he already knew.

There’s a ridiculous fistfight at the end between Duke and the villainous Gentry. Why JW didn’t just plug him on account of Gentry making his play first is beyond me.

I guess the fight is basically padding to make the film hit the fifty-four minute mark. In the meantime, Gabby / Dusty disappears from the film for almost a good twenty minutes – he was probably trying to master the art of frontier gibberish for the next film – then turns up just in time for the denouement.

There’s a nice stunt at the end in which Duke, being doubled by his stand-in, Yak Canutt, who plays yet another bad guy in the film, rides up to a cabin and throws himself through a window from his horse.

There’s yet another bout of fisticuffs between Duke and Gentry, Gentry then running from the cabin only to be met by a hail of bullets from the group of bozos that constituted his gang.

Duke gets the gal, so no surprise there. On the other hand, when you see for the very first time a rarely mentioned scene in which JW takes off for the pearly gates, you need to cut the film makers some slack every now and then.

Quite a memorable film for obvious reasons, and one I certainly won’t forget for a long time to come.

Santa Fe Stampede (1938) Republic, Dir: George Sherman, b/w, 55m

Cast: John Wayne, Ray Corrigan, Max Terhune, June Martel, William Farnum, Le Roy Mason

Get your hankies out for this one. The bad guys want someone else’s gold mine so bad they even kill a little girl. Land sakes, have they no heart?

The Mesquiteers grubstake their friend Dave (William Farnum) to work a gold mine on their behalf. When they turn up to say ‘hi’ to Dave his kids, Billy and Julie, fire at the Mesqs then come out from behind a rock brandishing a rifle each.

Lucky this wasn’t “El Dorado” or they’d both have gone the way of Johnny Crawford and ended up gut shot, kids or no kids.

Stony and the boys find out that Dave hasn’t got around to filing the claim yet on account of the corrupt mayor of Santa Fe Junction, Byron (LeRoy Mason). Meantime the trigger happy kids scare off a couple of hombres attempting to steal the Mesqs horses.

Our heroes give chase and take one of them, Joe Moffatt, off to jail. The other hombre meets up with Byron and shows him some samples from Dave’s mine which Byron intends to use in order to claim ownership of the mine for himself.

As usual, the town is a nest of corruption with the sheriff and the judge in hock to the mayor. When Stony tries to get Moffatt sent to jail his efforts are side-tracked by

Byron and a false witness. Moffatt goes free and the Mesqs demonstrate their contempt for the lack of justice by trying to beat up everyone within reach for which they end up being fined a hundred dollars each.

Instead of going down the vigilante route and running those dad-blasted hornswagglers out of town on a rail, Rusty urges them to do it legal like and issue a “right of appeal under the constitution”. Sounds kind of boring to me.

Cue a montage of lots of signed petitions and men riding around on horses for no particular reason. Meanwhile, Julie, the little girl with the loaded gun, starts lollygagging and lets on to one of Byron’s gang that she and JW and her daddy are off to lodge a petition of protest with the state governor in order to run the bad guys out of town.

The judge gets an attack of conscience when he realises that Byron is going to try and steal the mine from Dave and also stop Sandy and Dave from taking the petition to the governor, even if it means endangering the little girl.

You know. The one with the gun.

Moffat and another crony kill Dave and his daughter Julie and get the petition back, not realising that Stony has ridden off earlier to file a claim on the mine himself in Dave’s name. The dastardly Byron decides to frame Stony for Dave’s murder, making sure Stony doesn’t live to stand trial.

After filing the claim Stony is arrested by a friendly sheriff for the murder of Dave and the kid. Realising their friend is about to be railroaded the sheriff deputises Tucson and Lullaby and they accompany Stony back to Santa Fe Junction, much to the disappointment of Byron and the boys.

Byron then cooks up an idea to ensure that Stony doesn’t live to stand trial by spreading word around town that he’s going to go on trial elsewhere.

This results in the townsfolk transformed from law-abiding citizens into a mob of torch and pitch-fork wielding thugs straight out of a Universal Horror movie.

Ironically this is the exact thing Stony argued against in the first place. Not so much hung by his own petard as about to get just plain hung.

The judge eventually rediscovers his moral compass, ordering the corrupt telegraph operator to send a telegram asking for help for the beleaguered sheriff who is trying to protect Stony.

What more can I tell you? Billy the kid comes to the rescue, riding off to find Stony’s hapless companions and untying them so that they can then beat up their captors and ride back to town to help their boss.

Meanwhile, Stony starts looking more nervous than Joe Burdette whilst he sweats inside the jailhouse and the town mob grow uglier and uglier.

They eventually set fire to the place with JW still inside but a helpful stick of dynamite thrown into the mix blows out the back of the jail and he escapes, rescuing the unconscious

Nancy, played by June Martel, who hasn’t really figured all that much up until now, and won’t do for much longer seeing as the flick is nearly over.

It’s a bit of a lame ending with Stony confronting the bad guys, ending in the usual fistfight.

Byron gets away and for a moment, bearing in mind the film has broken the taboo of having a child killed for plot purposes, I thought that maybe little Billy might be skulking somewhere in the dark shadows ready to blast the villain with that gun of his, but it is not to be.

Stony punches Byron in the face instead and everyone lives happily ever after.

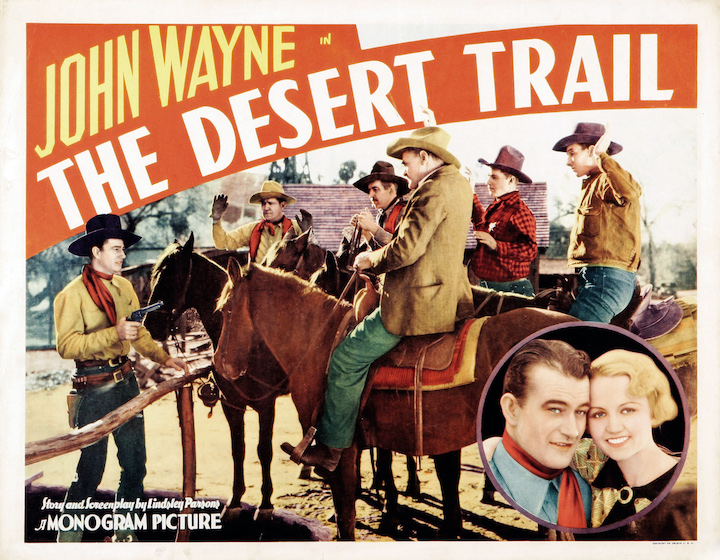

The Desert Trail (1935) Lone Star, Dir: Cullen Lewis, b/w, 54m

Cast: John Wayne, Mary Kornman, Paul Fix, Eddy Chandler, Carmen LaRoux, Lafe McKee

The opening sequence in this film is actually quite entertaining. Wayne, as rodeo rider John Scott, is travelling with his gambling friend, Kansas Charlie (Eddy Chandler), to Rattlesnake Gulch and the next rodeo where JW hopes to earn money roping a bunch of defenseless cows.

Charlie on the other hand is looking to rope in a bunch of loser gamblers by cheating in every hand.

The wisecracks and quips between the two of them as they vie for the attention of fellow stage passenger Juanita (Carmen Laroux), flow thick and fast, almost as if the resident scriptwriter, in this case, Lindsley Parsons, has been wired up to the mains in order to craft a script that literally crackles with witty wordplay.

Parsons also previously wrote the screenplay for “The Man from Utah”, for which I suggested in my review that things were starting to improve a bit on the Lone Star productions front.

Never mind though, we can’t always be right.

Just as with “The Man from Utah” the film is padded out with stock footage of a real rodeo event and, just as with the previous film also, Wayne stumbles into yet another one that is crooked.

When Charlie tells him he’s going to be cheated out of his winnings the two of them confront the organizer and threaten him at gunpoint unless he pays up. After they skedaddle, a couple of tough hombres, including Paul Fix as Jim (back on the John Wayne Soon-To-Be Stardom Express after a break of two years), try to rob the organizer of the rest of his money.

Aided and abetted by his partner-in-crime Pete, Jim plugs the rodeo guy in the process. Guess what happens next? Yup, that’s right. JW and his side-kick carry the can for the shooting instead.

Despite the cold-blooded murder committed by Jim, the film still steers a comedic path. There’s a certain bedroom farce vibe going on with bad guy Pete turning up at Juanita’s hacienda, having to hide when JW then barges in to try his luck as well.

Charlie then follows suit, his hands manacled after having been wrongly arrested by the sheriff and his posse earlier for the murder of the rodeo organiser.

Pete, who’s been in the closet all the while – not the kind of closet that dare not speak its name but the one located in the living area of the hacienda – emerges from his hiding place and robs JW and Charlie.

They separate for reasons too complicated to go into here, with Charlie disguising himself as a Preacher by turning his short collar back-to-front before he and JW follow Pete to Poker City.

They then bump into Jim as well, unaware that he’s partly responsible for them being on the run.

Pete appears to have a bit of a conscience regarding the killing of the rodeo guy but more importantly than that, he also has a hot sister called Anne (Mary Kornman), who will obviously at some point indulge in a bout of tongue wrestling with the Dukester – but there I go, getting ahead of myself again as usual.

JW and Charlie go off to apprehend Pete and Jim who are intent on robbing the local stagecoach.

The heroes interrupt the villains during the robbery, JW riding off to stop the runaway coach and Charley chasing after Pete and Jim.

He shoots Jim from his horse, Charlie telling him that he was the last person he ever thought would ever get involved in this kind of thing.

Jim replies ‘Pete made me do it and he made me take the stuff. Please don’t tell Anne’. Wimp.

Pete gets JW and Charlie arrested back in town by informing the sheriff they’re wanted for murder in Rattlesnake Gulch. Pantywaist

Jim finally decides to take matters into his own hands and help to exonerate his friends on account of his sister having the hots for Duke.

After Jim helps JW and Charlie break out of jail he gets it in the back from Pete who then goes on to rob the bank before fleeing on horseback.

JW and Charlie follow in hot pursuit, at the same time as being trailed themselves by the sheriff and his posse.

The inevitable shootout occurs, with presumably Yakima Canutt doubling for Wayne as he does that really clever diving from his horse through a cabin window thing, after which the proceedings are wrapped up by what I assume is a death-bed confession to his sister by Jim, who comes out with the usual “Pete made me do it” stuff.

You don’t actually find out if Jim dies but seeing as he shot the rodeo guy he’s going to get strung up anyway so it all ends quite happily.

Out of the early 1930s JW films I’ve reviewed up to this point “Desert Trail” is definitely a notch above what I’ve seen so far.

Wayne and his co-star Eddy Chandler spar with each other really well and I’m hoping it’s a partnership that makes it into the next few Lone Star entries in this series.

Duke comes across as more relaxed and even quite exuberant at times as if he’s finally starting to get into his stride as an actor, not just delivering his lines in a monotone as he did too frequently in the films that came before.

Also, when watching these early JW efforts it’s always worth keeping an eye out to try and catch the first appearance of a mannerism, idiosyncrasy or gesture that contributes to his later acting style.

In this film, I detected for the first time the habit Wayne eventually adopted of stopping in mid-sentence as if to catch his breath before then finishing what he has to say.

Check this one out. You’ll like it. It’s a real delight to watch.

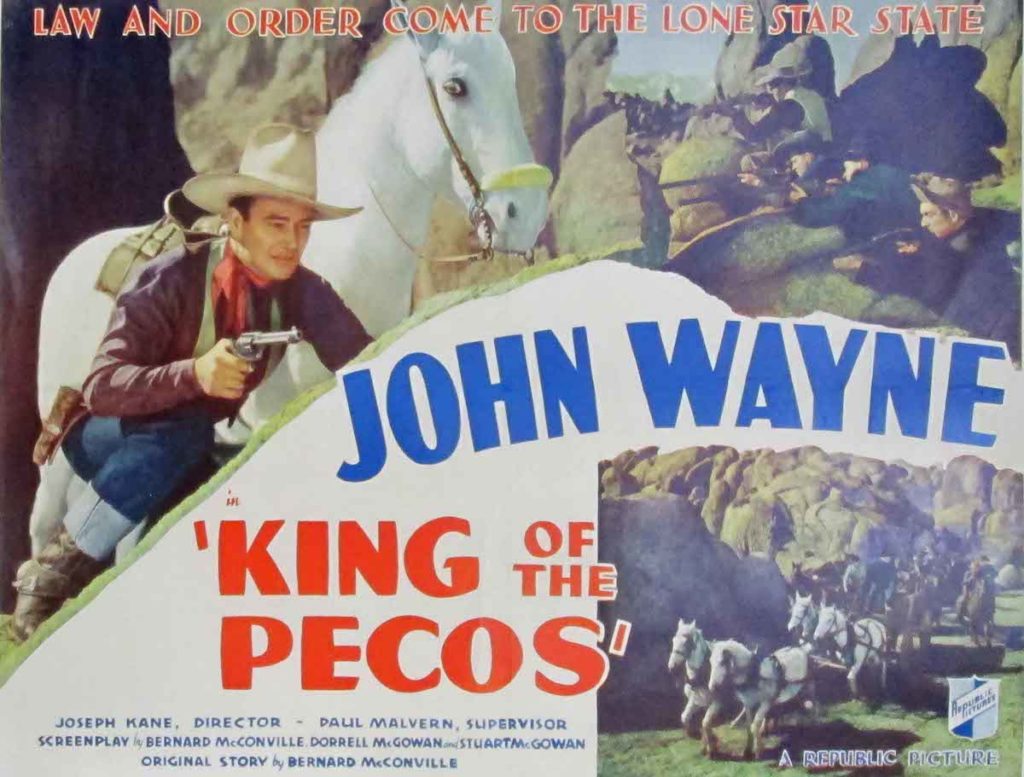

King of the Pecos (1936) Republic, Dir: Joseph Kane, b/w, 55m

Cast: John Wayne, Muriel Evans, Cy Kendall, Jack Clifford, Arthur Aylsworth, Herbert Haywood

Here’s another JW Western in which Yakima Canutt plays the bad guy again, this time a character called Henchman Pete. Don’t those outlaws ever have a surname?

Villain Alexander Stiles (Cy Kendall), has a habit of wandering into new territory and claiming it for his own under a concept known as “right of discovery”.

He soon discovers himself though that the locals don’t exactly appreciate this wanton act of land-grabbing, in particular, Ma and Pa Clayborn, who stand up for their rights and end up on the wrong end of a gun.

In a particularly brutal scene for the time their young son John, who grows up into a strapping young man with a heck of a resemblance to John Wayne, gets punched and whipped to the ground by one of the villains, Henchman Ash (Jack Clifford), for standing up to them.

A quick flashforward to ten years later shows JW practicing his gun skills whilst at the same time revealing he’s been studying law with one intent – to try the case of John Clayborn versus Alexander Stiles. I know who my money’s on.

Travelling on the stagecoach to the town of Exposition, JW hears that Stiles now owns the whole town of Cottonwood and a million acres of land as well.

In fact, in the last ten years, he’s become “the richest cattle king of the Pecos”. And Duke’s on his way to take the fat cat down, either with a law book or a gun. Or both.

Oh, and there’s a pretty girl by the name of Belle (Muriel Evans) on the stage as well, and we all know how that’s going to turn out too.

Within two minutes of hitting Cottonwood, JW finds himself face-to-face with the man responsible for the death of his parents and takes on his first case for a couple of locals who have been swindled by Stiles.

The court case never happens on account of Stiles being powerful enough to railroad the local sheriff and the county judge so JW decides to get his two clients to round up all the people who’ve been swindled seeing as he now has a case against Stiles which he’s going to pursue legally.

For a while anyway.

JW “Perry Mason’s” bad boy Stiles in court and paves the way for the swindled ranchers to get their water rights back.

Being the villain Stiles gets all the best dialogue, issuing the command to one of his minions to “Take the shortcut to Red Rock Canyon”, in order to waylay the crowd on their way to file for water rights.

To cut a long sequence short, JW and the good guys outsmart Stiles and the bad guys and manage to successfully file their claims.

Stiles decides to fire his lawyer who lost the court case on his behalf, and when we say fire we mean fire, on account of the lawyer getting shot full of lead in an out of court settlement.

The upshot of all this legal toing and froing is that the local ranchers are now very rich seeing as they can water and feed their cattle and sell them for twenty dollars per head.

Henchman Pete overhears them loudly agreeing to herd all of the cattle together and drive them to the cattle market in Abilene.

Stiles decides to deprive the animals of all drinking facilities seeing as he owns the town and water rights through which the herd will travel.

Belle’s dad gets a bullet after remonstrating with the Stiles gang when they try and relieve him of his cattle, which for some unexplained reason he’s decided not to sell just yet.

There’s a big shoot-out at the end between the opposing parties with Stiles making a run for it and getting shot in the process. JW catches up with Henchman Ash and settles the score with him in a genuine “High Noon”-type showdown at the end of the film.

The comedy duo of Hank (Arthur Aylsworth) and Josh (Herbert Haywood respectively – one of them is profoundly deaf and can’t hear what his partner has to say – grows a bit tiresome by the end but on a scale of one to ten I’d give this effort an eight.

It is, without doubt, the best so far of all the films John Wayne appeared in during his exile from stardom after the box-office failure of “The Big Trail” six years before.

Wayne still has a long way to go before he gets to the point where he appears comfortable in his own skin onscreen but the storyline is quite compelling and the locations in Lone Pine are magnificently captured by cinematographer Jack Marta.

One to watch for that small band of Western fans who have yet to see all of the films John Wayne ever made.

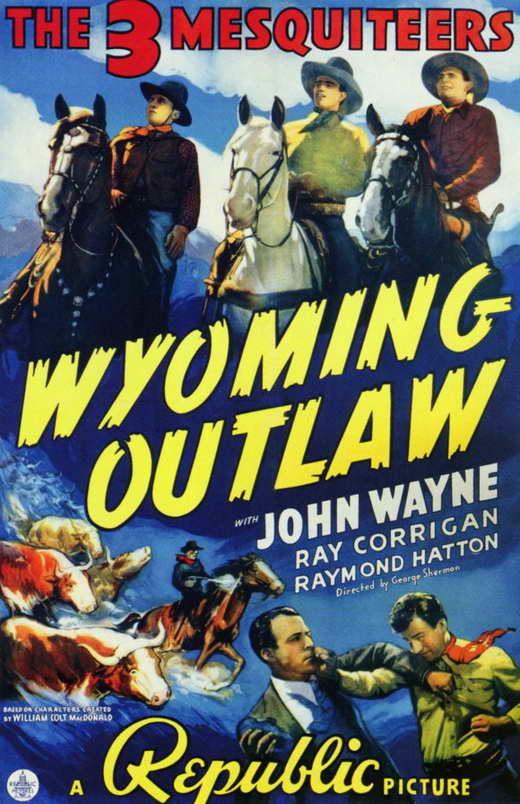

Wyoming Outlaw (1939) Republic, Dir: George Sherman, b/w, 55m

Cast: John Wayne, Ray Corrigan, Raymond Hatton, Charles Middleton, Don “Red” Barry, Pamela Blake

Good news, pardners. Someone at Republic saw the light and dropped Lullaby Joslin, the weird one with the wooden dummy, and replaced him with Raymond Hatton as Rusty Joslin.

Not only that but “Wyoming Outlaw” is a far cry from the previous Mesquiteer vehicles I’ve seen up to this point. The reason for this is a great central performance by Don ‘Red’ Barry’ as a down-on-his-luck farmer, Will Parker, who is forced to steal food in order to sustain his family after the price of wheat drops and forces him into penury.

Seeing as this is a Three Mesqs film you naturally still get the usual punch-ups, misguided intentions and hammy acting as before, but this time around the violence is real and people don’t get to dodge the bullets as before.

It’s as though someone with a sense of reality and social commitment has been let loose on the script and the end result is an entertainingly adult B-Western with not one wooden dummy in sight.

The only issue is that the timeline is skewed again, the story taking place in 1918 and apparently the Mesquiteers and their fellow cow herders were not aware America had entered the First World War.

Hiding from a huge dust storm, Stoney finds a conveniently placed newspaper that provides a little bit of social history for the audience as regards the reason for the storm.

It seems it’s the result of the land being farmed specifically to provide wheat during the conflict in Europe.

Once the war ended the price of wheat fell and most of the farmers were bankrupted, a situation not even the Mesquiteers could sort out.

Chancing upon the daughter of a dirt-poor farming family, Irene Parker (Adele Pierce), the Mesquiteers try and help as best they can but her brother Will ends up in trouble with the law when he insists on hunting protected game to feed his family.

Parker points out that ‘the right to eat should come before the right of game to live’. ‘Sounds like pretty good sense’, agrees Stoney. Not a film for animal rights campaigners then.

Once the story starts rolling the Mesquiteers take a bit of a back seat. They’re depicted more as bystanders in a situation that this time is taken out of their hands as Parker crosses the line into lawlessness and becomes an outlaw on the run.

The main thrust of the film is the animosity between the Parker family and crooked politician Joe Balsinger (LeRoy Mason), a situation created by the father Luke Parker (Charles Middleton) who stood up to Balsinger at one point.

Their enmity is compounded by Balsinger’s designs on Irene, a situation resolved by Stony’s fists. The Mesqs themselves fall foul of Balsinger when they offer to help out the Parker family, intervening when Ma Parker is forced to pay extortion money to Balsinger in the hope that he will give her husband a job.

The Mesqs get her money back which sets them up for a showdown with the politician.

After hot-headed Will is jailed for killing a deer for food, Luke Palmer is beaten up for attempting to testify to Balsinger’s nefarious dealings, forcing Will to break out of jail and visit some violence of his own on the villain of the piece.

He kills a couple of Balsinger’s henchmen during the escape and then hunts Balsinger down. The Mesqs try to do all they can to stop the violence before it gets too much out of hand but Will is determined to make Balsinger pay for his dishonourable behaviour.

Will finally catches up with his nemesis and confronts him, forcing the law to shoot both of them in the ensuing showdown.

This is a very good entry in the series, with co-stars such as Elmo Lincoln, the first Tarzan, and Charles Middleton, of Ming the Merciless fame, along for the ride. Don Barry packs a real punch as the doomed Will Parker and apart from the tacked on happy ending I’d thoroughly recommend this to anyone who professes a liking for all things Wayne.

If anyone would like to put forward their favourite Western from John Wayne’s pre-stardom days then please feel free to let us know in the comments.