Director John Sturges began his career in 1946, helming a number of popular film noirs in the early years with titles such as “Shadowed” and “The Sign of the Ram”.

Despite his eventual recognition as a director of Westerns, he didn’t actually dip his toe into the genre until 1949 with “The Walking Hills”, although it was a modern-day oater as opposed to a traditional example of the form.

This wouldn’t be the only time the director took on a modern day Western.

“Bad Day at Black Rock”, released in 1955, is one of his most accomplished pieces of work, a so-called ‘neo-Western’ set in 1945 and therefore a no-brainer when it came to including it in this article.

Sturges’s first ‘real’ Western was “Escape from Fort Bravo”, released in 1953, after which he turned out a series of classic cowboy films in the 1950s culminating in the Western he is probably best known for, “The Magnificent Seven (1960)”.

I’ve reviewed a number of his films for Mostly Westerns over the years so I thought it was about time to do a proper round-up of his cowboy films, which means that some of the reviews may be familiar to you already, whilst the films I’ve viewed recently are described in rather more detail than usual.

The films are considered chronologically and split across four articles. I may return to the subject again later on down the line and evaluate the films in terms of preference rather than chronologically.

In the meantime, I hope you enjoy part one which takes a look at “The Walking Hills”, “Escape from Fort Bravo” and “Bad Day at Black Rock”

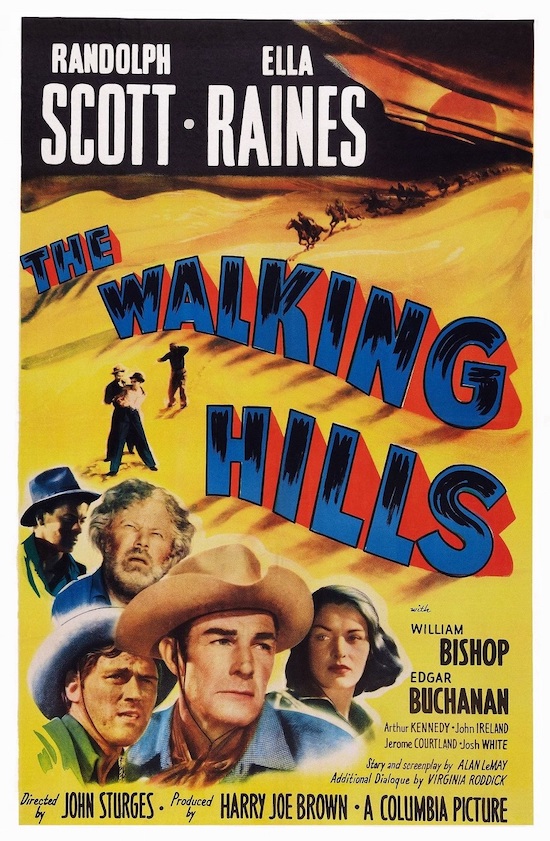

The Walking Hills (1949) Columbia Pictures, Dir: John Sturges, B&W, 78m

Cast: Randolph Scott, Ella Raines, Edgar Buchanan, William Bishop, Arthur Kennedy, John Ireland

“The Walking Hills” is at most a modern-day Western but the presence of Randolph Scott helps reinforce the notion it’s actually a Western in disguise.

The fact that the story and screenplay are credited to Alan Le May, who wrote the book on which the John Ford classic “The Searchers” was based also helps as well. The action is also set in a border town and you really can’t get more of a cowboy vibe than that.

Dave Wilson (William Bishop), archetypal stranger in the town of Mexicali on the Mexican side of the border, wanders into the back room of a cantina and is encouraged by horse breeder Jim Carey (no, not that one), played by Randolph Scott, to join in a poker game.

He is followed in quick succession by a man named Frazee (John Ireland), who has been hired to keep a close eye on Wilson.

One of the other card players, Old Willy (Edgar Buchanan) is regaling everyone about the story of five wagons that disappeared on the border a hundred years ago. The wagons were carrying a large shipment of gold worth five million dollars.

A younger man, Johnny (Jerome Courtland), who pays more attention to a calendar pinup (supposedly of Marilyn Monroe according to some sources but difficult to verify), casually mentions his horse nearly caught its hoof on an old wagon wheel in the very hills Willy was saying the wagons had disappeared in.

Cue a montage of furtive glances with Frazee ordering the cleaner, Bibbs not to leave the room.

Before you can say “Holy Treasure of the Sierra Madre”, the motley group of card players, including a drifter by the name of Chalk (Arthur Kennedy), resident cantina guitar player Josh (Josh White) and Carey’s hired Indian hand Cleve, are fully equipped with horses, food and water and on the trail of the missing gold.

The clue to their first hurdle is in the name the walking hills, the name given to the sand dunes that continuously shift and change shape in the desert wind, thus making it difficult for Johnny to relocate the wagon wheels he’d described earlier.

To make matters worse, a woman by the name of Chris (Ella Raines), has followed the group into the desert and cuts herself in the action as well, her actions revealing the thin veneer of trust between the group that begins to fracture in the heat.

Chris and Davy Wilson converse out of earshot of the rest of the group, it becoming apparent they have been involved romantically, Chris telling Davy, or Shep as she knows him, followed him to give warning that if Jim finds out about their relationship he might not take too kindly to having been cheated on.

We then have a flashback sequence in which it is revealed Shep and Chris, who are both rodeo riders, get into a rodeo of their own whilst out on the circuit, Chris leaving Jim in the process.

Back in the hills, other complications arise. First off Shep realises someone in the group has been signalling with a mirror to some unknown person back on the trail.

Finding a mirror which he suspects belongs to Chris, he puts in his and is then immediately fingered as the mirror man himself, and now viewed with suspicion by those who also saw the flashing communication.

Not too long afterwards, Cleve admits to Jim that he used to smuggle Chinese immigrant workers across the border through the hills and he now suspects Frazee is a government man on his trail.

Cleve is wrong though. Frazee is actually trailing Shep who confesses to Chris he never turned up to run away with her on account of having accidentally killed a man he caught cheating at cards.

He went on the lam and the dead man’s father hired Frazee to track Shep down.

Now, this is where it gets real complicated. Frazee is the mirror man, only he’s not using a mirror, he’s using a heliograph to stay in communication with a posse hired by the dead man’s father who have been following the group into the desert, ready to take back the murderer, Shep, for a quick trial and necktie party.

Frazee tries to bury the heliograph but Johnny catches him, Frazee shooting and wounding Johnny in the ensuing fight.

Jim takes an executive decision after the wounded Johnny tells him he’d rather die than go to prison, telling Cleve to hide the horses away from the camp in case anyone tries to sell Johnny down the river.

When Jim questions Frazee about who in the group he’s after, Frazee, who’s not letting on the identity of his quarry, instead tells him he’s stalling the posse on account of still wanting in on his cut of the five million in gold.

The discussion is interrupted when Willy thinks he’s hit paydirt, the rest of them joining to dig out a wagon from the and. Unfortunately, they don’t find any gold, so the search continues for the rest of the wagon train.

All of this is overshadowed by the imminent arrival of a sand storm.

Events then speed up, Frazee and Dave getting it on by trying to chop each other to pieces in a duel of shovels, Jim then saving Dave’s life by taking on Frazee himself, Cleve returning with the horses on account of the gathering storm literally minutes after Johnny dies from his injuries and then everyone deciding to get the hell out of Dodge in the face of the tempest headed their way.

In a fit of madness, Chalk shoots Frazee and tries to run off the horses, Jim eventually gunning him down then riding off on the last horse to get the rest of the scattered herd.

Once the storm dies down Jim, Dave and Chris meet up with Willy, Josh and Bibbs, Cleve having perished. The storm has uncovered the wagons completely but Willy tells Jim there isn’t any gold. Dave decides to give himself up, Chris joining him with best wishes from Jim as Dave he goes to surrender to the waiting posse.

There’s a slight twist at the end when Jim gets Willy to confess that there really was gold in them thar wagons, even if it was only ten thousand dollars.

This is a neat little B movie with a sterling cast that riffs heavily on “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre”, released the year before, without losing its own identity in the process.

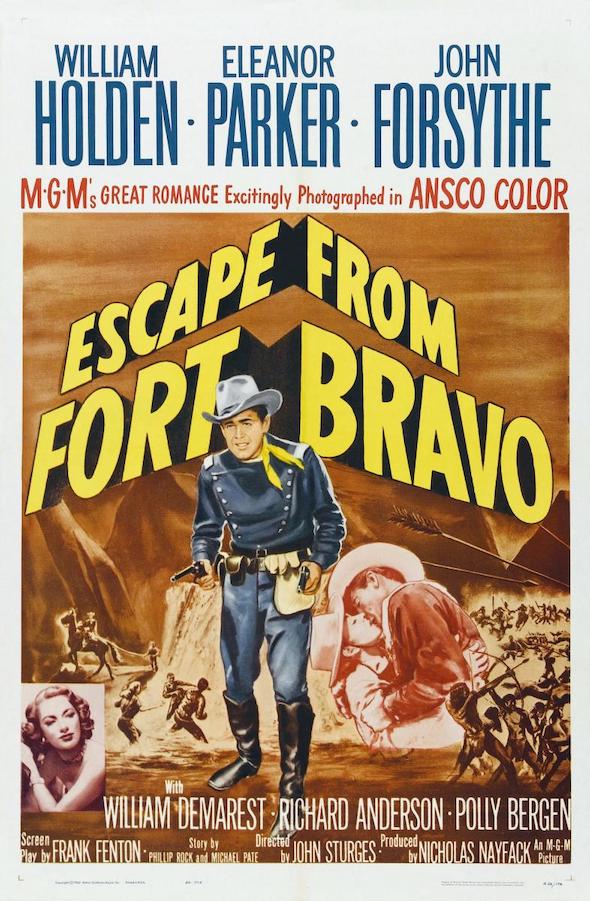

Escape from Fort Bravo (1953) MGM, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 98m

Cast: William Holden, Eleanor Parker, John Forsythe, William Demarest, William Campbell, Polly Bergen

“Escape from Fort Bravo” is one in a number of Westerns that have dealt with the incarceration of defeated Confederate soldiers by the Union army, other examples of this Western sub-genre stretching from “Two Flags West” in 1950 right through to “Major Dundee” in 1965.

In this relatively little-known John Sturges opus, William Holden is at his belligerent best as Union martinet Captain Roper, tasked with overseeing a prison camp host to rebel soldiers who are anxious to escape and get back to fighting on behalf of the South.

Into the mix comes the beautiful Carla Forester, who on first sight appears to have arrived at the fort as a wedding guest but in reality is there to help her former beau, Confederate captain John Marsh, played by John Forsythe, to escape.

To complicate matters both Carla and Captain Roper fall for each other, which makes things a bit awkward when he finds out she’s in on the jailbreak.

Roper tracks the escapees down with the intention of bringing them all back to the fort for punishment.

This is where the fun really starts because as they make their way through hostile injun territory the group is set upon by a bunch of Apache warriors who don’t give a damn which side is Union or Confederate. They just want to kill everyone.

The main set-piece of the film has Roper, his fellow soldiers and prisoners boxed in behind a ridge from which neither they nor the Apaches can see each other.

The Apaches decide the only way to flush their victims out is to estimate where the group is, then shoot their arrows into the air, picking off the least-known members of the cast first before hitting pay-dirt with Forsythe.

Naturally, the cavalry comes to the rescue just in the nick of time to save the good guys which is par for the course in this kind of film.

I used to get really excited as a kid when a cowboy film had cavalry and Indians in it and this was definitely one of the best.

If you haven’t seen it then I thoroughly recommend it, even though it’s nearly as old as I am.

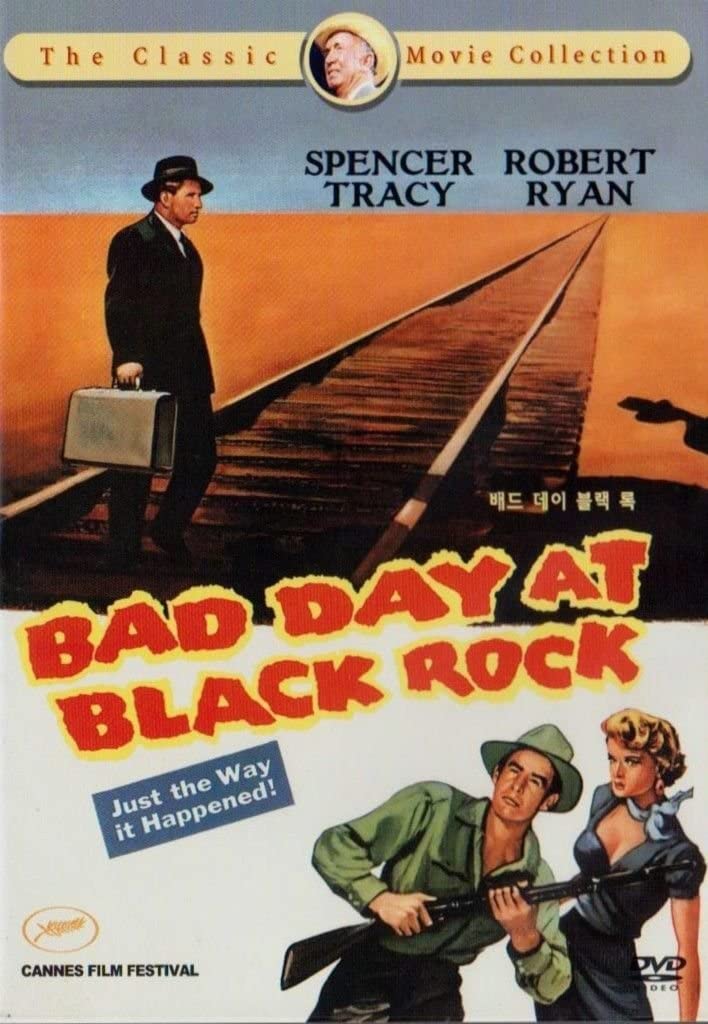

Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) MGM, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 81m

Cast: Spencer Tracy, Robert Ryan, Walter Brennan, Ann Francis, Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine

A stranger arrives in the town of Black Rock, only he’s not riding a horse, he’s travelling on a Southern Pacific streamliner passenger train, and he’s dressed in black.

The townsfolk are immediately alarmed as the train was not scheduled to stop at their town, a misbegotten collection of buildings located in the back end of nowhere.

In fact, according to the suspiciously nervous station clerk Mister Hastings (Russell Collins), the train had not stopped there in four years. The stranger, a one-armed man by the name of John Macreedy (Spencer Tracy) asks if there’s a cab to Adobe Flat.

When told ‘no’ he walks to the nearest hotel, his presence followed with interest by practically everyone in town including Doc Velie (Walter Brennan), Liz Worth (Anne Francis), Hector David (Lee Marvin) and Coley Trimble (Ernest Borgnine).

The hotel manager Pete Wirth (John Ericson) doesn’t exactly give Macreedy a warm welcome, informing the newcomer the place is full.

Ignoring Wirth he decrees he’d like a bath, insinuating his way into one of the rooms. Hector follows the stranger up to his room, telling Wirth he’s going to “crowd him a little. See if he’s got any iron in his blood”.

When Macreedy returns to his room after his bath Hector is sat on the bed waiting for him. They engage in a terse exchange in which the one-armed man decides it’s better to go and move to another room.

He then informs Wirth he’s staying at the hotel for the next twenty-four hours and goes looking to hire a car in order to drive to Adobe Flat.

As he leaves the hotel a car pulls up with a dead deer strapped on the bonnet and out of the vehicle gets Trimble and Reno Smith (Robert Ryan). The two men then join the group of townspeople gathered in the hotel.

Hector tells Smith that the stranger ‘pushes too easy’ at which point Doc pipes up, wanting to know why everyone seems so all riled up about Macreedy’s presence in Black Rock.

Smith tells Doc to leave it be then instructs Hastings to telegram a private detective in Los Angeles and ask that he dig up anything he can on a John J. Macreedy. They all then watch in consternation as Macreedy moseys on down the street to the local jail.

There he meets Sheriff Tim Horn (Dean Jagger) who appears to still be two sheets to the wind after ‘celebrating’ a bit too much with Doc the night before.

Macreedy asks if Horn knows of a man living out at Adobe Flat by the of Komoke. Horn reaches for the nearest whisky bottle and then refuses to answer any more questions.

Smith attempts to ingratiate himself with Macreedy, apologising for the suspicious reception he’s received. Macready tells him he’s looking for a man called Komoko.

Smith admits he knew the man, a Japanese farmer who was shipped off to a relocation camp when WWII started.

Their conversation is interrupted when Liz turns up in a jeep which Macreedy promptly hires from her then drives off to Adobe Flat.

Smith is not too impressed with Liz lending her jeep out to a stranger, especially a stranger asking u wanted questions about Komoko.

Word comes back from Los Angeles that there is no record or information available on Macreedy.

The simmering resentment at the strangers’ presence in Black Rock comes to the surface, Smith eventually forcing everyone to realise that they need to do something about Macreedy, the ‘something’ being of a terminal nature.

Meanwhile, Macreedy arrives at Adobe Flat to find only the burnt out shell of what was presumably Komoko’s house. On returning to the town he is followed by Trimble who crashes into the back of Macreedy’s jeep and runs him off the road.

Back at Black Rock Macreedy visits Liz in order to rent out her jeep again but this time she refuses to give him the keys, but not before he informs her of his suspicion that something bad has happened out at Adobe Flat.

He and Smith then have a frank and open exchange of views, Smith finding out that Macreedy lost his arm in the war.

He then asks why he’s looking for a “lousy Jap farmer”, his racism towards the Japanese finally coming to the fore. Macreedy in turn demands to know what happened to Komoko, Smith rattling off a story about a gang of kids burning down Komoko’s ranch after he’d been sent off to be resettled after the outbreak of WWII but Macreedy is having none of it.

Having noticed wildflowers growing out by Komoko’s house he suggests that the abandoned land looks more like a graveyard, implicitly telling Smith he knows Komoko is probably buried in an unmarked grave out at Adobe Flat.

After Macreedy fails in his efforts to call the State Police, Doc tells him the townsfolk are looking to kill him and he needs to stop snooping around. “It’s a little too late for that”, Macreedy replies, so Doc offers to lend him a hearse to get out of town.

As they try to get the vehicle to start Trimble appears and rips the wiring out from beneath the hood, effectively trapping the stranger in town.

Macreedy writes out a message for Hastings to send to the State Police then repairs to the local hostelry where he encounters Trimble who goads him into a fight.

To the surprise of everyone in the diner, and especially Trimble, it transpires Macreedy is proficient in karate, chopping the bully in the neck with his good arm and eventually knocking him out. He then accuses Smith of having killed Komoko and tells him he’s going to “go down hard” for what he did.

Gathering once more at the hotel Macreedy finds out that Hastings never had any intention of sending his telegram. When the sheriff finally gets up some courage to warn Hastings he broke the law by revealing the contents of the message to Smith he is relieved of his duties, Smith pinning the sheriff’s badge on Hector instead.

Left alone with Doc and Pete Wirth, Macreedy finally lets on that he came looking for Komoko to give him the badge awarded to his son who died trying to save Macreedy’s life, figuring it was the least he could do to “give him one day out of my life”

Doc confesses that Smith leased Adobe Flat to Komoko knowing the farmer would need water in order to be able to plant crops. Smith knew there was no water but when Komoko dug a well and discovered water for himself it made Smith “pretty sore”.

He didn’t like Japs anyway”, Pete Wirth chimes in, finally admitting that he, along with Smith, Hector and Trimble, got “patriotic drunk” after the attack on Pearl Harbour and rode out to Komoko’s ranch. Smith set fire to the house and shot Komoko when he tried to evade the flames.

Realising the jig is up Pete rings his sister to help get Macreedy out of town. Before that can be accomplished Pete and Doc take Hector out of action with Doc swiping him across the head with the end of a fire hose. Macreedy leaves the hotel and jumps into Liz’s waiting jeep but she’s not helping him escape, she’s delivering him into the hands of Smith instead.

She jumps out of the jeep which is suddenly illuminated by the headlights from Smith’s car, Smith firing at Macreedy from the dark. Smith then double-crosses Liz, shooting her in cold blood in order to set Macreedy up for her murder. Smith is unable to draw a bead on the one-armed man so he tries to outflank him in order to get a better shot.

In the meantime, Macreedy finds an empty bottle and fills it with fuel from the jeep.

Smith emerges from the rocks, Macreedy launches the handmade Molotov cocktail and Smith gets a taste of what he gave to Komoko, although he still lives. When Macreedy gets back to Black Rock he finds that ex-sheriff Tim Horn has helped round up Hector and Trimble.

The police – finally – arrive and take the miscreants into custody. As Macreedy waits for the streamliner to arrive and take him away from Black Rock, Doc asks if he can have the medal won by Komoko’s son to help rebuild the town. Macreedy hands it over and rides out of town.

This is one hell of a film with one hell of a cast with Sturges masterfully applying the use of Cinemascope to accentuate the sense of isolation of the town of Black Rock. I recommend it to all Western fans who have yet to see it.

Thank you for reading part one of our article on the Western films of John Sturges. Our second part will include reviews of “Backlash”, “Gunfight at the OK Corral” and “The Law and Jake Wade”.

You may also be interested in The Ranown Films of Randolph Scott or maybe

the Western Movies of Sergio Leone. Staying in the 1950s what about these western movies.

The Many Western Movies of John Sturges Part 2

Welcome to the second of our four-part article on the Western films of John Sturges.

Backlash (1956) Universal – International, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 84m

Cast: Richard Widmark, Donna Reed, William Campbell, John McIntire, Barton MacLane, Harry Morgan

With a script by Borden Chase, “Backlash” features a number of noirish elements that wouldn’t be out of place in some of the earlier films of John Sturges.

The film begins with a woman, Karyl Orton (Donna Reed), riding through Gila Valley and chancing upon a stranger, Jim Slater (Richard Widmark) whom she assumes is digging for gold in the valley.

Another stranger suddenly appears on a ridge and tries to shoot Slater, who thinks Orton has set him up. Slater beats hell for leather and rides out into the open in order to flush his would-be killer out.

He gets the upper hand and kills his assailant, only to discover he’s just shot a deputy sheriff.

Slater and Orton take the dead deputy back to Silver City whereupon the sheriff (Edward Platt) also accuses him of digging for gold but it turns out he was looking for the grave of his father.

Apparently, Slater’s dad was one of a group of five men who died at the hands of the Apaches, and Slater thinks there was a sixth person who got away when he could have helped save the group, opting instead to keep the gold the group was looking for all to himself.

The sheriff warns Slater that the dead deputy had two brothers, Jeff (Robert J. Wilke) and Tony Welker (Harry Morgan), and they won’t look too kindly on Slater for having killed their kin.

The sheriff runs Karyl out of town and tells Slater to skedaddle as well seeing as he doesn’t want any shooting in his town. Slater leaves Silver City before the Welker boys arrive,

making his way to the nearest military fort where he is advised to go and talk to Sergeant George Lake (Barton MacLane) who lead the detail that discovered the dead men in Gila Valley.

On the way to seek out Lake, Slater runs into an Apache war tribe out on the kill. By sheer coincidence, a stagecoach comes running down the trail bearing just one passenger, the aforementioned Ms. Orton.

Everyone makes a run for the nearest trading post where it transpires Sergeant Lake and his men are holed up under siege from even more Apache warriors.

Slater learns that Lake could only identify three of the bodies found in Gila Valley, one of whom had a missing hand, after which Karyl confesses her husband was also one of those looking for the gold, claiming that some of it now belongs to her.

Lake and Slater sneak out at dark to try and stampede the Apache horses, the idea being to give everyone else the chance to escape on the stagecoach.

Slater gives Karyl an unwanted smacker by way of saying goodbye. In return, she gives him an unwanted slap on the kisser. Fair deal all round.

The two men succeed in their task but Slater is fatally wounded as they try to make their escape.

Before he dies he tells Slater that the man who ran out on the five dead men in the valley rode a horse with a Texas brand on it belonging to a certain Major Carson down Texas way. Meanwhile, the Welker brothers are hot on Slater’s heels.

They arrive in the town of Tucson and helpfully overhear Karyl mentioning Slater in conversation whereupon they start to interrogate her as to his whereabouts.

Slater suddenly arrives in Tucson at the same time and chances upon Karyl in the company of the Welkers.

She gives up Slater to the Welkers, forcing Slater to kill Jeff, wound Tony and get a bullet in his shoulder for his efforts.

This time it’s his turn to do the slapping, whacking Karyl for setting him up. A contrite Karyl finds Slater camping outside town and tends to his wound, digging a bullet out of his shoulder.

She then tells Slater she wants to do a deal with him to find the gold after which they embrace in a passionate kiss.

Slater tells her about the sixth man who rode a horse with a Texas brand, Karyl swearing she is going to help him track the mysterious sixth man down.

When Slater passes out from a pain killer administered by Karyl, she discovers a letter from his father to a friend in which he lets on he’s found s fortune in gold in Gila Valley and for the recipient to let his son know to come and look him up sometime, confirming Donna’s suspicions that Slater was looking for the gold all the time.

Making their way to see Major Carson they encounter two of Carson’s men, one of them a bona fide psycho by the name of Johnny Cool (William Campbell).

When they meet Carson they realise the identity of the man with one hand Sergeant Lake buried is Carson’s son.

Carson tells them about a man who owns a big ranch nearby called Jim Bonniwell (John McIntire) who claimed to have struck a fortune of sixty-thousand dollars in Gila Valley, a man Slater now starts to suspect is Karyl’s missing husband but whom she thinks might actually be Slater’s father.

Carson and Bonniwell are engaged in a range war, Carson offering Slater a job as a hired gun, which he rejects, riding off alone to finally find out who Bonniwell actually is, informing Karyl that “There are things a man has to know and has to do, and it’s best he does them on his own”

Johnny Cool turns out to be a traitor, riding off to inform Bonniwell that Carson intends to make his play the following day.

Into the local saloon walks Slater and immediately gets into a fight with Cool, not realising the man with him is Bonniwell.

After Cool and his boss leave the saloon Slater asks where he can find Bonniwell, his question interpreted the wrong way by sheriff Olson who puts Slater under arrest.

Karyl rides away from Carson’s ranch in search of Bonniwell but encounters Tony Welker instead, who insists she finishes having the drink his dead brother was trying to force on her when Slater shot him.

Harry then faces off to Johnny Cool who has taken an interest in Donna, Cool proving to be faster on the draw. Bonniwell then turns up in town, confusing the sheriff who was under the impression Carson was going to arrive in town first.

Bonniwell guns down the sheriff and then wanders in to the jailhouse to discover Slater behind bars. It is at this point we finally find out that Bonniwell is Slater’s father.

Bonniwell lets on the sixty-thousand was actually from a bank robbery, not buried gold.

Karyl’s husband had tried to ride off with the dough along with the other men in the group but Bonniwell let them walk into a trap with the Apaches then rode off with the money himself.

The inevitable face-off between Cool and Slater finally takes place, Slater proving to his father that he was good with a gun.

The son then faces off against his father, determined to warn Carson and his men before they can be slaughtered by Bonniwell’s men laying wait for them in town.

Bonniwell approaches his son intent on killing him when one of Carson’s men finishes him off. Slater and Karyl walk away to start a new life together.

As mentioned earlier “Backlash” is a noir-flavoured Western that keeps the audience guessing throughout as to the motives of the main characters.

For example, the female protagonist Karyl Orton is a femme fatale who one moment happily gives up Slater to a couple of killers but then in the end walks off arm-in-arm with him. It’s a film that keeps you guessing right up to the end which makes it watchable right up until the final scene.

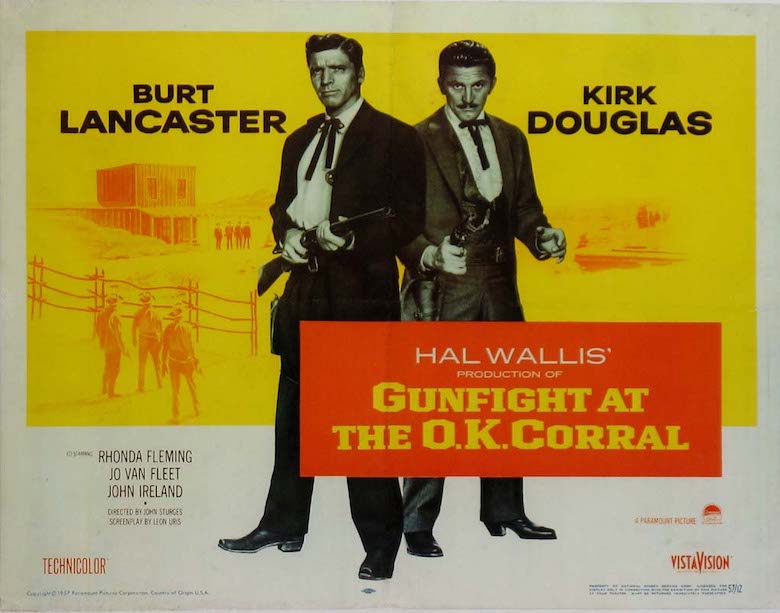

Gunfight at the OK Corral (1957) Paramount, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 122m

Cast: Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Rhonda Fleming, Jo Van Fleet, John Ireland, Lyle Bettger

Released in May 1957, “Gunfight at the OK Corral”, is yet another in a long line of attempts by Hollywood to recount the story of the famous encounter between the Earps and the Clantons in the town of Tombstone in October 1881.

In this version, the two central characters of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday are played by Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas respectively.

Sacrificing historical accuracy for good old-fashioned dramatic license, the film effectively builds up the tension over a fairly long running time of two hours and twenty minutes before the screen eventually explodes into action.

Before we get to that point the audience is presented with Lancaster and Douglas competing with each other for acting honours, Douglas choosing to play Holliday as highly-strung and constantly agitated whilst Lancaster settles for cool reserve, something that Henry Fonda aimed for in the earlier John Ford classic, “My Darling Clementine”, both the film and Fonda the bar against which all other Wyatt Earp movies should be measured.

It’s Douglas who dominates though, even if he doesn’t go the whole hog and cop it at the end in the OK corral gunfight like Victor Mature did in Ford’s version.

There’s a stellar supporting cast at work here as well including the Queen of Technicolor herself, Rhonda Fleming, playing the love interest of Earp, as well as an interesting collection of cowboy regulars such as John Ireland, Jack Elam, Lee Van Cleef and a very young-looking Dennis Hopper as the doomed Billy Clanton.

One can also find lurking in the background other familiar faces including DeForest Kelley as Morgan Earp, Earl Holliman and Kenneth Tobey.

Dimitri Tiomkin provides a stirring soundtrack whilst Frankie Laine warbles the theme tune. Combine all of the above and you have the ingredients for a classic Hollywood Western, which the director and cast deliver with aplomb.

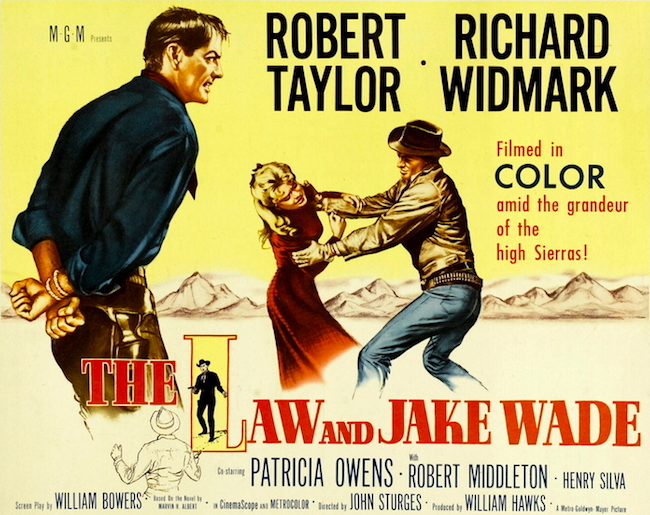

The Law and Jake Wade (1958) MGM, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 88m

Cast: Robert Taylor, Richard Widmark, Patricia Owens, Robert Middleton, Henry Silva, DeForest Kelley.

“The Law and Jake Wade”, released in June 1958, features Robert Taylor as Jake, Richard Widmark playing bad guy Clint Hollister with shades of Tommy Udo from “Kiss of Death” whilst the inevitable love interest role goes Patricia Owens as Jake’s lady Peggy.

In the beginning, Jake turns up to rescue his friend Clint from jail in return for Clint having done the same for him earlier on, which is obviously a big mistake seeing as Clint then smacks the sheriff over the head for serving him runny eggs and guns down three men before riding out of town.

Before a parting of the ways Clint asks Jake about the twenty-thousand dollars they’d stolen a while back, Jake confessing he’d buried the money then left it where it was in an effort to try and leave the bad times behind and turn over a new leaf.

And what a new leaf it is. Jake rides into his home town, enters the marshal’s office, then takes off his coat to reveal he’s actually the marshal.

Things turn dark when Clint turns up with his fellow psychotic followers in tow, including Robert Middleton as Ortero, Henry Silva as the somewhat vicious Rennie and DeForest Kelley playing the seriously deranged Wexler.

After kidnapping Peggy the gang force Jake to take them to where he buried the money from their earlier heist.

Unfortunately for all concerned, the local Comanche contingency has declared war on all white people within a hundred mile radius – again – resulting in Jake and his trigger happy captors finding themselves in a whole lot of trouble.

The film takes a noirish turn as one by one the baddies succumb to death by arrow as the Comanche infiltrate the town at night.

After Wexler and Rennie are dispatched to the happy hunting grounds, leaving the gang now whittled down to Clint and Ortero, Jake is forced to reveal where the loot is buried.

Jake gets the drop on Clint, having thrown a gun into the saddlebag along with the money. Ensuring that Peggy is going to be protected by Ortero who turns out not to be as psychotic as the others, Jake provides Clint with a gun and they finally have out the confrontation that’s been promised from the very beginning.

Seeing as Robert Taylor has top billing he gets to gun down Widmark like the dirty dog that he is.

Whilst not exactly a classic Western in the vein of “Shane” or “The Searchers” it’s still a highly entertaining shoot-em up with a convincing performance in particular by Widmark who dominates the film throughout.

Partly shot on location in the High Sierra, Sturges and cinemaphotographer Robert Surtees take full advantage of the spectacular landscape, capturing the wilderness in all its glory in wide-screen Cinemascope.

The Many Western Movies of John Sturges Part 3

Welcome to the third of our four-part article on the Western films of John Sturges.

Last Train From Gun Hill (1959) Paramount, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 90m

Cast: Kirk Douglas, Anthony Quinn, Carolyn Jones, Earl Holliman, Brad Dexter, Brian Hutton

The minute the film starts you just know the soundtrack is by Dimitri Tiomkin, sounding very much like an early version of his wonderful score for The Alamo.

A Native American woman, Catherine (Ziva Rodann), and her son Petey are out driving in their buggy in the countryside when they ride past two strangers, Rick Belden (Earl Holliman) and Lee Smithers (Brian Hutton).

The men, who have been drinking, follow behind on horseback. Belden makes a not very subtle pass at the mother whom he refers to as “Squaw Missy”. She hits him across the face with her horsewhip and rides off, Rick now all fired up and looking for revenge.

During the chase the buggy overturns, giving the two men the opportunity to have their way with the woman, whilst the young boy, Petey, rides off to find his father, Marshal Matt Morgan (Kirk Douglas) in the town of Pawley.

Morgan discovers that his wife has been raped and murdered and that one of the killers has left their horse at the scene, the saddle adorned with the initials CB.

A still drunken Rick cools off in a saloon in the town of Gun Hill when in walks Beero (Brad Dexter), informing him that his father, Craig Belden (Anthony Quinn) has been looking for him and wants to know where his favourite saddle is, the one with the initials CB on it.

It soon becomes apparent that daddy is not someone to be trifled with, the relationship between him and his son dysfunctional to say the least. He lays down the law, telling Craig “I want that saddle and the man who stole it”

Back in the town of Pawley, Morgan reveals that he knows the saddle belongs to Craig Belden, and having worked with Belden before is convinced he’s not the killer, but he’s going to Gun Hill to see his old friend anyway.

Catherine’s father exhorts Morgan to find the man who murdered his daughter and to “Kill him. Kill him slow. The Indian way”, to which the Marshal replies, “I’ll kill him…my own way”

On the train to Gun Hill, Morgan ends up in conversation with Craig Belden’s girlfriend Linda (Carolyn Jones), who recognises her boyfriend’s saddle. When the train arrives Linda is met by Beero, who is about to confront Morgan about the saddle hung over his shoulder.

Morgan instinctively knows Beero works for Belden and tells him to inform his boss he’s coming to see him.

Morgan meets up with Craig at his ranch and initially rekindles their old friendship, the Marshal realising that his friend wasn’t the man who killed his wife.

He tells Craig the only lead he has on the murderers is that Petey told him whoever killed Catherine had lashed the man’s face open with her whip.

Craig suddenly realises that Matt is actually looking for his son Rick. It’s obvious to Matt by his friend’s sudden change in demeanour that Rick killed the Marshal’s wife.

The conversation ends with Matt telling his former friend that he’ll leave on the last train from Gun Hill and that he’ll have two men with him, one of them “with a cut cheek”.

When he goes to serve two warrants for his wife’s killers to the local law officer Sheriff Bartlett (Walter Sande), Matt is forced to face the fact that Craig Belden owns the town of Gun Hill and everybody in it, including Bartlett.

Meanwhile, Craig finally confronts his son and Lee about the murder of Catherine, running Lee off of his ranch and then telling Rick he knows he murdered Morgan’s wife.

Rick rides off to town to confront and kill Morgan but his father tells him to wait until he himself arrives in Gun Hill, ordering Beero and another ranch hand, Skagg (Bing Russell) to stay close to Rick and protect him.

Morgan gets both a drink and free advice from the bartender to leave Gun Hill while he still can. In the saloon, he meets up again with Linda. She tells him if he’s looking for Craig Belden he ought to try a gin mill across the street.

Morgan follows up on her lead and encounters Rick, knocking him out and taking him prisoner. He then shoots his way out of the saloon, killing Skagg and a couple of others in the process. He confronts the sheriff in the main street and requests he takes Rick into custody.

Bartlett refuses, forcing Morgan to hole up with Rick in the nearest hotel and wait for the last train out of town leaving in another six hours.

Craig and his men saddle up and ride off to Gun Hill, learning on the way that Morgan has arrested Rick.

Within minutes of reaching town Craig lays siege to the hotel room where Morgan has Rick handcuffed to the bed. Taking a break from the gunfight Craig repairs to the main saloon and bumps into Linda.

She tells him they are no longer an item after she spent ten days in hospital from a beating he gave her, the result of him having paid too much heed to the lies Rick had told his father about her.

Despite her anger towards Craig she agrees to go and try to bargain with Morgan for Rick’s life, emphasising to the Marshal that she’s also trying to save his life as well.

Morgan doesn’t go for it but he does ask Linda if she could help get him a shotgun. Linda declines, goes back to the saloon, encounters Lee and asks him what happened back at Pawley.

When he tells her what he and Rick did to Morgan’s wife she walks off in disgust, at the same time catching sight of a shotgun behind the saloon bar.

In sheer desperation Craig tries to bargain with Morgan, taking along some backup to try and get a shot at the marshal but Morgan is too quick, shooting a couple of Craig’s men.

Rather than kill Craig for his treachery Morgan lets him off the hook, seeing as his old friend saved his life once.

Linda then turns up with the shotgun and hands it over to Morgan. Minutes later Lee sets the hotel on fire whilst Linda is betrayed by two of the townsfolk who inform Craig she sneaked a shotgun to Morgan.

Morgan leads Rick out of the burning hotel with the shotgun placed under the killer’s chin, threatening to blow his head off if Craig gets in his way.

He and Rick then slowly ride out of town standing on a buckboard, Craig, his cronies and the townsfolk walking helplessly behind as the sound of a whistle in the distance heralds the imminent arrival of the last train of the day.

Everything appears to be going Morgan’s way when the loose cannon that is Lee turns up the station and draws on the marshal.

Morgan blows him away with the shotgun but not before Lee has got off a shot, accidentally killing Rick in the process.

A grief-stricken Craig calls out Morgan, forcing him to draw. The marshal is faster, mortally wounding Craig who, before he dies, tells his old friend to raise Petey good.

Shades of “High Noon” hover over the film throughout, although this time everyone is waiting for a train to leave town rather than arrive.

Kirk is as granite-jawed as ever and Anthony Quinn is Anthony Quinn as usual. Earl Holliman is suitably sleazy as rapist killer Rick, as is his sidekick Lee, played by Brian Hutton, or Brian G.

Hutton as he became known a few years later when he turned to directing and helmed a number of action movies including “Where Eagles Dare” and “Kelly’s Heroes”.

Sturges shows with this film that he was at the top of his game when it came to handling mounting tension and suspense in any given situation, whether it be the build-up to the showdown in “Gunfight at the OK Corral” or the final prison breakout from Stalag Luft III in “The Great Escape”.

And he still hadn’t made his most famous film yet, which we now consider as follows…

The Magnificent 7 (1960) United Artists, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 128m

Cast: Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Horst Buchholz, Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughan, Brad Dexter, James Coburn, Eli Wallach

It’s not worth going through the plot of “The Magnificent 7” as the assumption is that anybody reading this article will already know the story, but if you haven’t seen it yet, then stream / steal / beg / borrow the film from the nearest available outlet and sit down for two hours and eight minutes of pure unadulterated cowboy action, helped of course by the famous soundtrack composed by Elmer Bernstein.

“The Magnificent Seven” is, without doubt, one of the most popular cowboy films ever made.

As everyone knows, it’s a remake of Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai”, transplanted from medieval Japan to bandit-ridden Mexico.

Yul Brynner is ostensibly the main star but the film also belongs of course to the likes of Steve McQueen, James Coburn and Charles Bronson who, along with Robert Vaughan, Brad Dexter (the one nobody ever remembers) and Horst Buchholz collectively make this one of the best casts ever assembled for a Western.

Eli Wallach plays the dastardly Mexican bandit leader, Calvera, in an early rehearsal for his role as Tuco in “The Good the Bad and the Ugly” a few years later.

Legend has it that McQueen wanted the part of hired gun Vin so badly he faked a car accident in order to get out of his contractual commitment to the TV show “Wanted Dead or Alive” and the rest, as they say, is history.

He also famously spent a lot of time trying to upstage his co-star Brynner whenever the opportunity arose, prompting Brynner to caution him that every time he tried it on all he, Brynner, had to do was take off his hat to reveal his bald head and all eyes in the audience would be on him and not McQueen.

The soundtrack by Elmer Bernstein is practically the eighth member of the Mag 7, something Bernstein pointed out himself when he appeared in concert in London back in 2002.

He told the audience that the rough cut of the film was a bit slow, pointing specifically to one scene in which the seven meander past a big tree on their horses as if out for a Sunday afternoon picnic.

Bernstein decided the film needed a score that would inject some energy and urgency into scenes such as this and came up with what is now probably the best-known Western soundtrack of all time.

The final gunfight between the seven and Calvera’s band is probably the most memorable sequence in the film but the one that stays with a lot of people is the face-off between the luckless Robert J. Wilke and James Coburn, who turns out to be an expert knife-thrower.

Another case of instantaneous death Hollywood-style but Coburn is so imperturbable in that scene he gives Steve McQueen a real run for his money in the “who’s the coolest dude?” stakes.

When it comes to good old-fashioned shoot-em-ups it doesn’t get any better than this. The best of John Sturges by a mile.

Sergeants 3 (1962) United Artists, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 112m

Cast: Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford, Joey Bishop, Henry Silva

Apart from “Fast Company”, which he directed in 1953, John Sturges is not necessarily known for his work within the comedy genre, so it’s a bit of a mystery as to why he was hired to helm “Sergeant’s Three”.

This is the second movie to feature all the original members of the fabled Ratpack celebrities and, with a script by W.R. Burnett as well as cinematography by Winton Hoch of ‘She Wore A Yellow Ribbon” fame, this film should have been so much more entertaining than the end result turned out to be.

The script by W.R Burnett, who generally worked on more serious fare such as “Little Caesar” and “High Sierra”, is a thinly-disguised remake of “Gunga Din” with Sammy Davis taking on the role of the outsider played in the earlier version by Sam Jaffe.

The plot revolves around a fanatic Sioux warrior by the name of Mountain Hawk who urges his followers, known as the Ghost Dancers, to go to war with the white man. Into the mix wander the three sergeants of the title, Mike (Frank Sinatra), Chip (Dean Martin) and Larry (Peter Lawford).

Mike and Chip spend most of their spare time attempting to dissuade Larry from marrying his sweetheart Amelia, after which he would then leave the military. They’re sergeants three in the style of the Musketeers – all for one and one for all (or “All or Nothing at All” if you’re a Sinatra fan)

When Mountain Hawk and his war party invade the town of Medicine Bend, Mike and the boys wipe out most of them in the first half hour of the film, thus making the Ghost Dancers a fairly short-lived movement.

To be honest it’s all a bit slow and too languid to call it an action film. The film plays heavily on the stereotype persona of Dean Martin as a man of the drink whilst Sammy goes missing for vast tracts of the running time, required to do a little dancing and trumpet playing before getting skewered on the pointed end of a spear in the climactic showdown with Mountain Hawk.

In the final analysis, it’s a curiously detached exercise in which some sequences die out like a blank squib.

One sequence in which Sammy’s sick mule is revived with a mixture of herbs and whisky fades into nothing, an anti-climax at best. It’s as though the film is caught between having to satisfy the audience with plenty of action yet at the same time cater to rat pack fans looking for a laugh.

In the end, neither wins out and it’s no wonder the movie has been dubbed ‘the lost Sinatra film’.

At the end, Mike orders that Larry, who is about to leave the army and ride off with his sweetheart, be arrested for desertion, a final joke that also turns up in the later remake of “The Front Page”, which was directed by Billy Wilder. I can’t help thinking that Wilder might have been a better choice to direct “Sergeant’s Three”.

We’ll be wrapping up our consideration on John Sturges and his Westerns next time with a look at “The Hallelujah Trail”, “ “Hour of the Gun” and “Joe Kidd”.

The Many Western Movies of John Sturges Part 4

Welcome to the final part of our epic 4 part article on the Western films of John Sturges

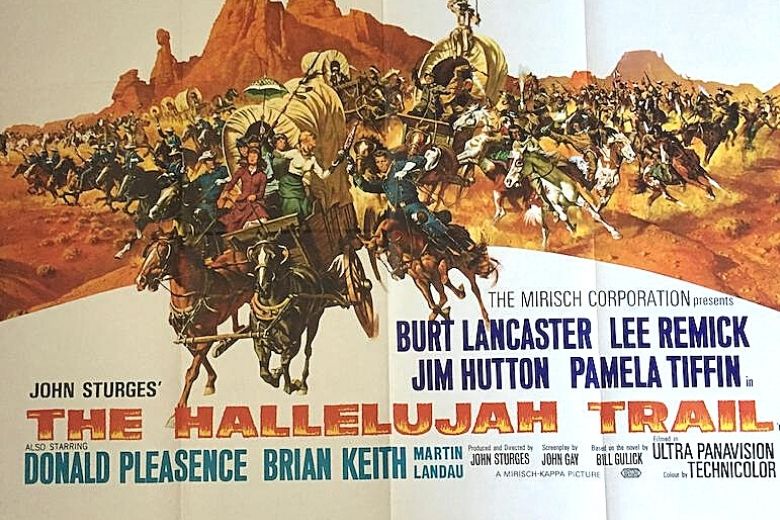

The Hallelujah Trail (1965) United Artists, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 165m

Cast: Burt Lancaster, Lee Remick, Jim Hutton, Pamela Tiffin, Donald Pleasance, Brian Keith

Variously described at the time of its release as a “two and a half hour episode of ‘F Troop’” and ‘an amiable but lumbering Western satire”, it has to be said that, in the intervening years, time has not been too kind to “The Hallelujah Trail”.

My main memory of the film, having seen it when it was first released on the big screen, is one of a highly enjoyable comedy Western with lots of laughs and a great soundtrack by Elmer Bernstein. In the cold light of day, however, it’s still got a great soundtrack but not much else.

I actually watched it all the way through again for the purpose of this article but only scratched down a couple of pages of notes which means this review will not be going into as much detail as usual.

Filmed in Ultra-Panavision and marketed under the Cinerama banner, making “The Hallelujah Trail” one of a dwindling number of ‘event’ movies Hollywood was so fond of back in the day, the story is set in the year 1867 and tells of a time when Denver City ran out of sippin’ whiskey.

The film is accompanied by a voice-over narration provided by actor John Dehner that serves to inform the audience of the movements of specific groups of people – the Sioux, the cavalry, the citizens of Denver, the teamsters – who are involved in solving the problem of how to get their hands on the whiskey being shipped to the town.

Winter is going to be closing in soon so the goods need to be delivered as quickly as possible. The aforementioned factions, however, have their own plans.

The Sioux want it for themselves naturally, because, as we all know, Native Americans were apparently only ever interested in one thing, and that was to consume as much ‘firewater’ as they could get their hands on.

The Irish teamsters are intent on getting their hands on the cargo as well because they’re, well, you know, Irish, and of course, the Irish do love their whiskey. Into the mix arrives a feminist temperance movement who want to stop men enjoying themselves because they’re women and of course, that’s what they do.

Finally, the military is there to keep order and to make sure the consignment of whiskey reaches its proper destination and does not fall into the wrong hands.

The only time the film came close to reminding me of why I thought it was so entertaining back in 1965 was the scene near the beginning when the townsfolk seek advice from their local oracle, a man coincidentally referred to as Oracle, and played with relish by British actor Donald Pleasance.

He is plied with what remains of the dwindling supply of whiskey left in Denver City in order that he can foresee something everyone knew all along, which is to order a consignment of hooch before winter comes.

Burt Lancaster plays the put-upon commander Colonel Thaddeus Gearheart as if he’s appearing in a serious film as opposed to a comedy.

So does Brian Keith as Frank Wallingham, the man who arranges for the delivery of the whiskey, whilst everyone else plays it for laughs.

Everyone else includes Lee Remick as temperance leader Cora Massingale, Jim Hutton as Captain Paul Slater, Pamela Tiffin as Louise, the love interest of Slater and daughter to Gearheart, and Martin Landau and Robert J. Wilke as Sioux warriors Walks-Stooped-Over and Chief 5 Barrels respectively.

Apart from the aforementioned soundtrack the only other saving grace of “The Hallelujah Trail” is the spectacular stunt sequence towards the end where the Sioux lose control of the wagons loaded with booze, after which, somehow or other, the whiskey disappears beneath a load of quicksand.

The end result is that Wallingham and Oracle await the reappearance of the lost whiskey as the quicksand slowly gives up the barrels one by one whilst in the final scene Gearheart and Cora plight their troth along with Slater and Louise in a double wedding.

I guess it’s too much to expect that what was so entertaining to the mind of a fourteen-year-old boy back in the mid-1960s would still be as amusing nearly sixty years later but, to me anyway, “The Hallelujah Trail” just doesn’t hit the funny bone anymore.

I assume, seeing as John Sturges also produced the film, that he knew at the time what he was doing, particularly after his overwhelming success a few years before with the superlative WWII movie “The Great Escape”, but success eluded him this time around, “The Hallelujah Trail” flopping big time at the box office.

When you consider the lukewarm reception of “Sergeants 3” a few years before one can only conclude that John Sturges was not that adept when it came to comedy and leave it at that.

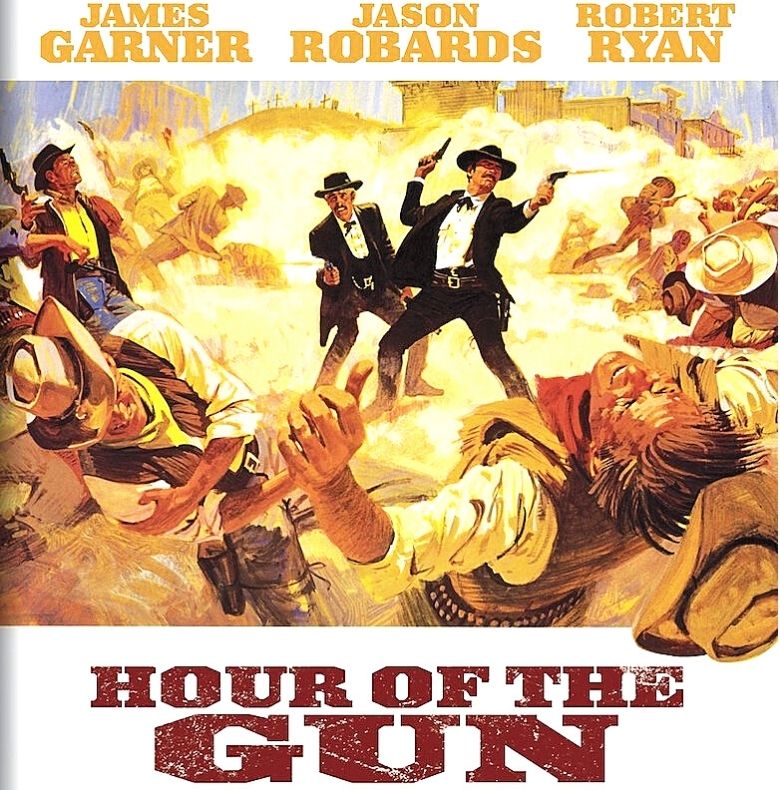

Hour of the Gun (1967) United Artists, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 100m

Cast: James Garner, Jason Robards Jr., Robert Ryan, Albert Salmi, Charles Aidman, Stephen Ihnat

“Hour of the Gun”, a welcome return to Western movie form for Sturges, takes up where his previous film on the subject, “Gunfight at the OK Corral” finished. This time it’s the turn of James Garner and Jason Robards Jr. to star respectively as Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, the story following in the aftermath of the showdown at the OK corral.

The film starts with the famous gunfight as a reminder of what happened, the credits proclaiming ‘This picture is based on fact. This is the way it happened’.

A decade on from the earlier film, Sturges now has the freedom to adopt a more open attitude towards the depiction of violence in the old West, Garner’s interpretation of Earp a sight more callous and menacing in tone than that of Burt Lancaster.

At one point, as they pursue Ike Clanton, played by Robert Ryan, and his gang of killers, Earp declares to Doc that he “doesn’t care about the rules anymore”.

The film then goes on to chart the previously moral and upright Earp’s descent into lawlessness, eventually disregarding due process of law.

This is demonstrated when a ruthless Earp starts tricking his adversaries into shooting first, knowing he’ll always beat them to the draw.

The climax of the film is a tense showdown between Earp and Clanton.

Earp takes off his badge, indicating he’s not going to go for all that ‘hands up and unbuckle your gun belt’ stuff.

Earp shoots Clanton dead – which is factually incorrect thus negating the claim at the beginning of the film – but it brings matters to a satisfactory conclusion as far as the audience is concerned.

Choosing to gloss over the relationships that Earp and Doc indulge in with the opposite sex as depicted in “Gunfight at the OK Corral”, Sturges concentrates instead on both the friendship between the two men, with Robards giving a great portrayal of Doc, as well as the war between Wyatt and the Clanton’s.

In my humble opinion, it scores a pretty high rating in the list of the best Earp / OK corral movies ever made, coming very close to stealing the number two spot from “Tombstone”, which starred Kurt Russell in the role of Wyatt Earp.

Number one goes, as always, to John Ford’s “My Darling Clementine”.

Stating the obvious, “Gunfight at the OK Corral” and “Hour of the Gun” would make a great double bill if you’ve got nothing better to do on a Saturday afternoon. A welcome return to form for Sturges as well in terms of his Westerns after the disappointment of both “Sergeants 3” and “The Hallelujah Trail”.

Joe Kidd (1972) Universal, Dir: John Sturges, Colour, 88m

Cast: Clint Eastwood, Robert Duvall, John Saxon, Don Stroud, Stella Garcia, Gregory Walcott

Clint and director Sturges make a great team in this very entertaining ‘landowner versus the revolutionary peasants’ tale.

Kidd is an out-of-work bounty hunter turned-town-drunk who finds himself embroiled in a dispute between land-grabbing Frank Harlan, played by Robert Duvall, and a Mexican revolutionary, Luis Chama, played by John Saxon.

Harlan puts together a posse to hunt Chama down and offers Kidd a job, which he declines. Then Kidd finds out Chama has attacked his ranch – although how Joe manages to keep a ranch going with all that boozing is never explained.

He subsequently throws in his lot with Harlan and the fuse is then set for a showdown between all parties concerned.

When I saw this film for the first time an acquaintance told me how delighted he was to see that this was the first Western to correctly show how a bullet can leave a rifle and hit the target before making a sound.

How he knew this I never found out. Sometimes it’s best not to ask.

Anyway, the scene in question features a long-range telescopic rifle shootout between one of Harlan’s men and Kidd, with Kidd winning the day on account he’s the best shot.

He also manages to get the upper hand on another Harlan acolyte, played by Don Stroud, the thug Clint has to hunt down in “Coogan’s Bluff”.

At the end of that film, he feels sorry for Stroud and offers him a smoke. This time though, Clint must have run out of cigarettes and just offers poor old Don a broken neck instead.

In the climax to “Joe Kidd”, Clint gets to ram a locomotive through the wall of a saloon, after which he polishes off what’s left of Harlan’s men in deadly quick-fire Man With No Name style.

He then puts paid to Harlan’s real estate development plans by plugging him as well, bestowing upon Robert Duval the distinction of being shot on screen by both Eastwood and John Wayne.

Kidd then hands Chama over to the sheriff, prior to which he punches the sheriff for an earlier infraction of etiquette. To really rub salt into the wound, he then rides off into the sunset with Chama’s girlfriend Helen, played by Stella Garcia.

Clint brings much more of a relaxed and laconic air to his performance in “Joe Kidd”, in contrast to the occasionally overwrought thespian talents of co-stars such as Robert Duvall and John Saxon.

His performance is also aided and abetted with a great script from Elmore Leonard. It’s safe to say that for his last Western Mr. Sturges went put with a bang.

Let’s not forget that John Sturges didn’t just direct Westerns. He was equally adept working within other genres too, as films such as “The Great Escape”, “Ice Station Zebra”, “McQ” and “The Eagle Has Landed” attest to.

However, it is his Westerns that show him at his best, especially the amazing quartet of oaters Sturges directed between 1957 to 1960, “Gunfight at the OK Corral”, “The Law and Jake Wade”, “Last Train from Gun Hill” and “The Magnificent 7”.

If he’d only ever helmed those four movies alone John Sturges would still be rightly celebrated as a master of the Western form.

We may revisit this article at some point in the future in order to rate all of the Westerns directed by John Sturges in order of preference. In the meantime, thanks for reading it and hope you enjoyed our take on the films we covered in the article.