I recently wrote an article listing my 10 Best John Wayne Westerns I saw as a child. The reaction was very positive but quite a few people lamented the omission of John Wayne classics such as Red River, McLintock and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, to name a few.

This is, therefore, an attempt to round up those JW cowboy movies – in chronological order – that didn’t make that first list, starting with the Westerns he starred in back in the late 1930s and the 1940s. I’m going to concentrate on what I consider to be the better known of the Wayne Westerns from this period, so you won’t find films such as The Spoilers or Tall in the Saddle in this list, although I may go back to consider them at some point.

Stagecoach (1939)

How could I have not included Stagecoach in my first article on Wayne’s Westerns? Simple really. It was made about 14 years before I was born but having spent so much of my life watching, writing and researching John Ford and cowboy films in particular I feel it’s a part of the fabric of my life.

It has everything you would want in a Western – John Wayne, Apaches on the warpath, a drunk doctor (who still manages to deliver a baby without dropping it), a gunfight, a lady of the night, a card sharp, charging cavalry, a stagecoach even – and to top it off, Monument Valley in all its glory.

I could write an article purely on the magic that is Monument Valley but maybe I’ll leave that for another time. Suffice to say that Stagecoach is up there in the pantheon of Westerns along with Shane, The Searchers, Red River, High Noon and The Wild Bunch – and the bonus is that not only did it finally make Wayne a star but it helped elevate the Western back to its deserved status as a major Hollywood genre.

1939 wasn’t exactly starved of classic Western fare – there was Dodge City, Jesse James and even Ford’s own Drums Along the Mohawk to contend with – but Stagecoach is top of the list for that year.

Bearing in mind John Ford is known mainly for his Western movies this was the first time he had directed in this genre since the silent days – the last Western he made previously to Stagecoach was Three Bad Men back in 1926. It’s fair to say that he set the bar for the cowboy films that followed and Wayne was an essential ingredient of major ‘A’ status Westerns from then on.

Although he was second on the bill to Claire Trevor, who plays a prostitute with a heart of gold, the film revolves mainly around his character, the Ringo Kid, and his determination to avenge the death of his brother at the hands of the Plummer gang. You could argue that the whole story of the stagecoach chase and ultimate rescue by the cavalry is a mere anti-climax to the final shootout between Ringo and his brother’s killers.

It’s almost two films rolled into one and Ford keeps the action moving almost from the minute the stagecoach leaves for Lordsburg. Wayne is still in his innocent cowboy phase – good with a gun but naïve and inexperienced when it comes to the female sex. On the other hand no one watches a Wayne film for the romantic content – The Quiet Man an exception – but to watch him in action and Stagecoach has more than enough of that to please even the most casual viewer.

Everything else you could say about this film has already been written and said. When it comes to Westerns, Ford and Wayne are the gift that just keeps on giving, and after Stagecoach it only got better.

Angel and the Badman (1947)

I must admit this is one of those rare things; a John Wayne film I’d not seen before – and you can include North to Alaska and practically all of the 1930s Republic films in that bag as well.

I thought I’d review it in this roundup as quite a few people appear to like the film so I thought I’d finally get around to checking it out myself. It starts quite well with the opening credits showing a chase sequence filmed against the backdrop of Monument Valley.

The score is by Richard Hageman who composed and arranged the soundtracks for Stagecoach and Fort Apache, so it’s fairly obvious we’re in Ford country – until we find out it’s written and directed by James Edward Grant, the man who eventually became Wayne’s go-to writer in the following years.

Not that I’m saying that counts against the film – after all Grant wrote or co-wrote The Comancheros and Donovan’s Reef, but then he was also involved in Big Jim McLain and The Barbarian and the Geisha – and I truly believe that if it wasn’t for Grant’s script then The Alamo would have been hailed as a truly great film.

It’s a great John Wayne film, no doubt about it, but in my opinion, the screenplay lets The Alamo down quite badly. Anyway, I digress.

Duke is in easy-going and congenial mode here as the injured outlaw Quirt Evans, nursed back to health by a Quaker family, and in particular by their daughter, played by Gail Russell, who can’t help falling for Wayne. It occurred to me as I watched it that the film has quite a lot in common with the Harrison Ford movie, Witness, which has almost the same plot. Wayne / Ford, Quaker / Amish, Gail Russell / Kelly McGillis, it’s all there if you look for it.

There’s even a shootout at the end of both films, along with the presence of a young boy in the midst of the action, although in Angel and the Badman, the kid is the younger brother of the Quaker girl, whereas in Witness he’s the son of Kelly McGillis.

And unless I blinked and missed it I don’t remember any scene in which Gail Russell washes her half-naked body while John Wayne watches from the doorway. Damn the Hays Code, that’s all I can say.

I was pleasantly surprised by the appearance of Harry Carey Senior as Marshall Wistful McLintock – what a great name – who occasionally drops into the film to remind Wayne he’s a wanted man.

Carey is still sporting the same gesture of scratching his face with his thumb that he employed countless times in the many silent films he made with John Ford as Cheyenne Harry. He also gets to save the day at the end of the film, gunning down the evil Bruce Cabot and his companion before they get the draw on Duke.

On the basis of Harry Carey’s presence in this film I think I might be inclined to check out The Shepherd of the Hills as well at a later point.

I have to say I quite liked this film, irrespective of James Edward Grant’s involvement, and Wayne’s pleasant and almost jovial performance is a delight to watch. I don’t, however, consider it to be a major entry on Wayne’s acting CV but nevertheless, it’s a likeable little film in its own right.

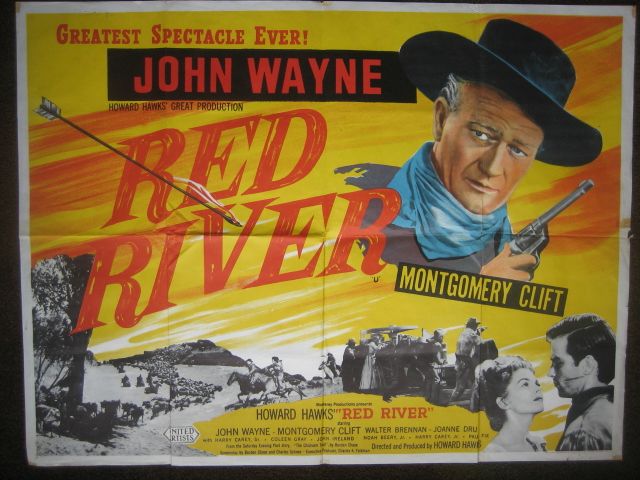

Red River (1948)

1948 was a good year for John Wayne and Westerns with audiences treated to the release in quick succession of Red River, Fort Apache and 3 Godfathers – one Howard Hawks and two John Ford’s in 12 months.

I don’t think it ever got any better than that. If there is such a thing as a towering Duke performance, then Red River has it in spades. Dimitri Tiomkin’s thunderous marching theme (which as all you Wayne fans know serves as the melody for My Rifle, Pony and Me in Rio Bravo – and when is someone going to release the original recording of the Red River soundtrack?) immediately announces that we are in the company of a classic Western from the very first frame, and both Hawks and Wayne deliver the goods accordingly.

In Wayne’s first Western for Hawks, he plays the determined and stubborn Texas cattleman Tom Dunson, a character more in tune with the complexities of Ethan Edwards and Tom Doniphon than the straightforward and uncomplicated cowboys he had played previously.

This is the period in Wayne’s career when he starts to show real range in his acting abilities, famously prompting Ford to declare after seeing Red River that ‘I didn’t know the son-of-a-bitch could act’.

As the film progresses Dunson gets meaner and more unlikeable, and it’s a credit to Wayne that he was confident enough in his acting abilities to play such an aggressive and unpleasant individual as Dunson at this point in his career.

A number of film writers have pointed out the similarity between the story to that of the mutiny on the Bounty, with Wayne as Captain Bligh and Montgomery Clift, Dunson’s adopted son who eventually takes control of the cattle drive, as Mr. Christian.

Although I think there’s an element of truth in that the film stands on its own two feet as a classic Western in its own right. The only false note for me is the ending, in which a murderous Wayne goes gunning for Clift. In the climax of the film, they engage in a vicious fistfight which is then abruptly terminated by the intervention of Joanne Dru, playing Clift’s love interest.

It just feels to me as though no one could come up with a more convincing ending – apparently, the original ending had to be changed as it bore too close a resemblance to a previous Hawks film, The Outlaw – but I have to admit in the scheme of things it doesn’t hurt the overall impact of the film in general and Wayne’s magnificent performance in particular.

Red River is notable for the first time that both Harry Carey Senior and Junior appeared in the same film, although they don’t share any scenes. It’s also famous for some of the off-screen shenanigans of Joanne Dru and John Ireland, who plays the gunfighter Cherry Valance.

Apparently, Hawks himself was quite smitten with Miss Dru and didn’t take too kindly to her preference for Ireland (Dru and Ireland eventually tied the knot and remained happily married for all of 8 years). The upshot of this is that Ireland’s character disappears about halfway through the film, only to turn up briefly at the end to be beaten to the draw by Wayne. I guess that’s what you get for messing around with the Sheriff’s gal.

Fort Apache (1948)

The journalist-turned-director Peter Bogdanovich once wrote that if you viewed the films of John Ford in terms of chronological narrative ie start with Drums Along the Mohawk which is set during the American war of Independence then move on to the Civil War with The Horse Soldiers and the settling of the West with Wagonmaster etc, you would be presented with a fairly comprehensive lesson on the history of America.

Based on that premise, if you want to know what happened to General Custer, look no further than Fort Apache. Wayne’s first Western with Ford since Stagecoach nearly a decade before, and the first in the director’s unofficial cavalry trilogy, the film tells the story of a strait-laced career officer, Lt Col Owen Thursday, played by Henry Fonda, who takes command of the outpost where Wayne, as Captain Kirby Yorke, is also stationed.

Fonda’s character leads his men to a glorious but meaningless death a la Custer at the end of the film, leaving Wayne, who has missed out on the action due to insubordination, to deliver the eulogy for the dead men.

Although Fonda is ostensibly the main star of the film this is where Wayne takes up the baton as Ford’s leading man from now on, Fonda appearing only once more in a Ford film with the troubled production Mister Roberts in 1955. Wayne’s final speech, and his best moment in the film, praises the actions of Thursday and his men, calling to mind the line from the later The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance that, when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

The story of Kirby Yorke doesn’t finish here though. Wayne reprises the role in Ford’s Rio Grande a few years later, accompanied by some of the same actors from this film. Fort Apache is the first time Wayne works with Victor McLaglen, here playing Sergeant Mulcahey, after which he then appears as Sergeant Quincannon in both She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande.

However, the role of Sergeant Quincannon in Fort Apache is played by Dick Foran – keep up at the back there. Ford stock company perennials Ward Bond and Hank Worden also feature in Fort Apache, making this and the other two entries in the trilogy a real family affair. We also get another lesson in how not to act from John Agar. How that man ever got the equivalent of an American equity card is totally beyond me.

3 Godfathers

This is a real gem of a movie and a great ensemble piece for Wayne, Harry Carey Jr, and Pedro Armendariz. It’s also the third version of the story, which should basically be subtitled The Three Wise Men Go West.

Ford had made a silent version back in 1919 called Marked Men, with Harry Carey Senior playing the role reprised by Wayne in this version. There was also an earlier sound version released in 1936 but this is probably the definitive version. Wayne, here playing a character called Robert Marmaduke Sangster Hightower, and along with his two bandit compatriots, stumble upon a dying woman about to give birth while they’re on the run from a local posse.

This time we get Duke in affable mood, one of Ford’s ‘good bad men’ in the mould of the Ringo Kid and modeled on Harry Carey Senior’s Cheyenne Harry character from Ford’s silent period. It’s safe to say we’re not in Searchers or Liberty Valance territory here. In fact, it’s almost a continuation of the character Wayne played the year previously in Angel and the Badman, Duke’s career at this point in time obviously going through its baby-holding period.

Carey Senior died a year before the film was released and Ford had put his son, Harry ‘Dobe’ Carey under contract to his Argosy production company. This was Dobe’s first film for Ford, and he’s quietly impressive as the Abilene Kid.

If you want the lowdown on how Ford treated his new young actor during the filming of 3 Godfathers, then look no further than Carey’s highly readable book, Company of Heroes, in which he recounts how Ford made him suffer during the filming of his death scene which took place in Death Valley. Dobe’s wife, Marilyn, told me when I met the couple back in 2007 that there were times when Ford could be quite scary to be around. Read the book and you’ll find out why.

Wayne also acquits himself very well in this film. It’s less of an action film, however, and more an obvious Biblical parable, with the three outlaws giving up the opportunity to escape from the law in order that the child of the dead mother survives.

Duke eventually delivers the baby to safety just in time for Christmas. And just in case the audience still doesn’t get the point he takes the baby to a town called New Jerusalem.

Despite Ford’s somewhat sadistic treatment of Carey Junior, the director pays a poignant tribute to Harry Carey Senior at the beginning of the movie. He filmed a short scene using Cliff Lyons, who eventually ended up working as a stuntman and helped Wayne with the battle sequences in The Alamo, doubling as Dobe’s dad on Carey Senior’s favourite horse, Sonny.

The film is ‘Dedicated to Harry Carey, a bright star in the early Western sky’. I think that’s why out of all the films Dobe appeared in, it was a DVD copy of 3 Godfathers that I asked him to sign for me. Not a genuine Ford masterpiece, and not your typical Wayne cowboy action film, but highly watchable just the same.

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)

If anyone has any doubts about Wayne’s acting ability, his performance as the retiring Colonel should convince otherwise.

Playing a character older than the actor was at the time, Captain Nathan Brittles, Wayne convinces completely as the elderly soldier called upon to perform one last mission – to help negotiate peace between the warring Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes – before heading off to retirement.

This is less an action film and more a rumination on growing old, the scene towards the end of the film when he and Chief Pony That Walks discuss going hunting, fishing and drinking reinforcing the anachronistic nature of the two characters.

For some strange reason, Wayne seemed to think when he was interviewed in 1971 for Playboy that he had been nominated for an Oscar for this film. Unfortunately, that turns out not to be the case but he was definitely robbed in my opinion, delivering a more studied and measured performance here than he did in Sands of Iwo Jima which was released in the same year, for which he did actually receive his first Academy nomination.

There is a bit of a clunky love triangle sub-plot featuring Joanne Dru, Harry Carey Jr and John Agar – yes, him again – that detracts from the main story of Wayne’s impending retirement.

That’s a small price to pay though when matched against Wayne’s bittersweet acting – witness the scene where his troop presents him with a gold watch ‘with a sentiment on the back’ – along with Ford’s peerless direction and the Oscar-winning cinematography of Winston Hoch. Before The Searchers, I don’t think Monument Valley has ever looked so beautiful and Hoch captures the landscape like never before.

Add to that the performance of Victor McLaglen as the Irish sergeant also on the cusp of retiring – I’m guessing he must have re-enlisted for Rio Grande – and you have a perfect example of how Ford and Wayne can deliver the goods when they’re both firing on all cylinders.

Coming to this website soon – The John Wayne Round Up Part II, featuring… well I can’t say – you’ll just have to wait (I can’t wait). Check out the original article of The 10 Best John Wayne Westerns From My Childhood… and beyond.

Make sure to sign up below and never miss any posts.