Sergio Leone only directed eight films in his short but impressive career.

His first two movies were examples of the popular sword and sandal Italian movies of the late 1950s / early 1960s, Leone credited as an assistant director on “The Last Days of Pompei”, released in 1959, and then as director for “The Colossus of Rhodes”, released in 1961.

His filmography also lists him as having worked on the Hollywood biblical epics “Ben-Hur” and “Sodom and Gomorrah”.

It is for his game-changing Westerns, however, that Leone will forever be remembered, so go sling on your poncho, get that pistol that always shoots more than six bullets, light up your cheroot and hit the trail with us as we take a look in part one at the Dollar trilogy.

This trio of films bestowed worldwide fame on Leone and in the process turned Clint Eastwood into a bona fide Hollywood superstar.

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

Just like Wayne, Clint Eastwood languished in Poverty Row, only in the 1950s it was called television.

Playing the second lead character, Rowdy Yates, in “Rawhide”, he had a respectable following but no one ever figured he’d become one of the biggest Hollywood stars of all time.

“A Fistful of Dollars” changed all that of course and the rest, as they say, is history.

I’ve already remarked in a previous article about how cinema audiences were stunned when “A Fistful of Dollars” was released only to see that nice Rowdy Yates turning up as a “monosyllabic psychopath with no name who shoots first and doesn’t bother asking questions afterwards’.

Actually, he does have a name. He’s called Joe but The Man With No Name has more of a ring to it. “A Fistful of Dollars” wasn’t released in the UK until 1967 despite having been released in Italy in 1964.

This delay was in part due to Japanese director Akira Kurosawa suing Leone for stealing the story from Kurosawa’s samurai movie “Yojimbo”, released in 1961.

Kurosawa walked away with a lot of money, and Leone ended up getting A Fistful of Nothing for directing the film, although he more than made up for that with the two films that followed.

The story involves stranger Joe riding into a town controlled by two factions, the Baxter’s and the Rojo’s.

He plays one gang off against the other, the Rojo’s eventually eliminating the Baxter’s, and Joe doing the same to the Rojo’s. In between all of this, there’s a subplot involving a kidnapped woman and her young son whom Joe rescues and returns to their rightful family, indicating that the unforgiving killer actually has a soft spot.

Just to show he’s also vulnerable, Joe gets the excrement kicked out of him by the Rojo’s, accompanied as usual by a cacophony of unfiltered chuckling and chortling on behalf of the permanently amused gang members.

Watching it again I’m still struck, as I was when I first saw the film, by Sergio Leone’s cartoonish approach to the Western.

It’s halfway between parody and pastiche, with dying cowboys twisting like tops and throwing their arms into the air like children might do when pretending to be shot.

This notion of play-acting is reinforced by the complete absence of blood in the gunfight scenes. One character even suggests that it’s like ‘playing cowboys and Indians’, a line that I’m assuming is supposed to be ironic.

The film also throws in the standard cliché of Mexicans forever laughing uncontrollably whenever they drink, shoot or maim. It’s like a laughing gas canister has exploded in their midst and they just can’t control themselves.

Until The Man With No Name turns up of course and wipes the smile from their faces, and then they laugh no more.

I should mention here the innovative sound of Ennio Morricone’s soundtrack, or Dan Savio as he was known in the original credits for the film. Leone was called Bob Robertson and the magnificently over-the-top villain, Gian Maria Volonte, was known as John Wells, a name I notice he was still associated with on the 1968 vinyl soundtrack release.

“A Fistful of Dollars” is an extremely entertaining and ground-breaking film and Westerns were never really the same after this – I’ll leave you to consider if that was good, bad or just plain ugly.

After all these years I’m still undecided myself, but on the positive side, it made a star out of Clint Eastwood, an actor who showed he was a worthy successor to the likes of John Wayne, Alan Ladd, Randolph Scott and James Stewart when it came to the Western. The only difference between them and Eastwood is that he spoke less and shot more people.

For those who might not be aware, the story for “Yojimbo” was used again in 1996 as the basis for the Bruce Willis gangster film, “Last Man Standing”, directed by Walter Hill.

Although it didn’t do that well at the box office it’s a good film, and Kurosawa, along with scriptwriter Ryuzo Kikushima, finally got the credit they deserved.

For a Few Dollars More (1965)

In the second of the Dollar trilogy, Eastwood returned as The Man With No Name, playing a poncho-wearing silent killer with an unlit cigarillo clenched between his teeth. In other words, just like the character he played in “A Fistful of Dollars”, although for some reason he now goes by the name Monco, not Joe.

Other than that it’s business as usual. This time though, Eastwood is joined by veteran Hollywood Western actor Lee Van Cleef, playing a pipe-smoking bounty hunter, Colonel Douglas Mortimer, who competes with Eastwood in the killing stakes. As “A Fistful of Dollars” did with Clint, this film finally propelled Van Cleef into much-deserved popularity and stardom and boy, did he make the most of it!

The real star of the movie, however, is Gian Maria Volonte, reprising his psycho Mexican bandit performance as Ramon Rojo from the previous Dollar film.

Here he plays El Indio and, if possible, is even nastier than he was in the first film, smoking dope to calm his nerves whilst reminiscing on the time he raped a young woman who subsequently killed herself.

The scene in which he forces a man to listen whilst his wife and young child are murdered to the accompaniment of a stolen timepiece (musical chimes courtesy of Ennio Morricone), before shooting the unfortunate husband dead, is genuinely chilling to watch.

You’re just aching for the moment for Indio to get his just deserts, which he finally does at the end of Clint’s gun.

One standout moment in the film is when Van Cleef strikes a match on Klaus Kinski’s bearded cheek, Kinski playing a hunchbacked gang member called Wild. In response to this outrage, he sweats and twitches like a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs (that was the least offensive metaphor I could find).

If twitching and sweating were an Olympic sport, then Kinski would take win gold every single time. Despite this obvious talent, Van Cleef eventually shoots him anyway.

Apart from Gian Maria Volonte, a couple of other familiar faces from the previous film also turn up, including Maria Brega and Josef Eggar. What also turns up is another example of “let’s beat the living daylights out of Clint Eastwood” to yet another soundtrack of uproarious laughter.

The final gunfight sequence, in which Mortimer gets to avenge his sister, the girl Indio had raped, looks like a rehearsal for the closing scene in the final part of the trilogy. Speaking of which….

The Good the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

This is it. This is the one. As Quentin Tarantino maintains, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” is ‘cinematically perfect’.

I wholeheartedly agree.

Not for me the sombre aesthetic of “Once Upon a Time in the West” or the ‘amoral non-engagement’ – I know, I have no idea what that means either – of “Duck, You Sucker!”.

Sergio Leone’s final entry in the Dollar trilogy is, without doubt, the best Western he ever made. It runs just short of three hours and I could watch it multiple times and never get bored. It’s got a great cast and is also blessed with the best soundtrack Ennio Morricone ever wrote, bar none.

The opening sequence pre-echoes the beginning of Leone’s “Once Upon a Time in the West”, with Al Mulock, the actor who also plays one of the ill-fated trio in the later film, facing into the camera as he and two other killers close in on the bandit Tuco, played by Eli Wallach.

Tuco blasts all three of them then jumps through a glass window, his image freeze-framed along with the description as “Ugly”. Lee Van Cleef as bounty hunter Angel Eyes turns up next, and we know he’s going to be “Bad” after he shoots someone in the face through a pillow four times.

It’s a whole seventeen minutes before Clint, as Blondie, finally graces the screen, and within sixty seconds he’s already killed three men. And he’s supposed to be the “Good” one?

Although there’s an attempt to restrain the annoying constant laughter of the villains that on occasion blights the earlier films in the trilogy, Eli Wallach takes it upon himself to deliver lots of out of context giggling in a shamefully scene-stealing role as Tuco.

Van Cleef is not as benign as bounty hunter Mortimer was in “For a Few Dollars More”, but Clint’s character displays a bit more compassion than usual. We see him stroking a kitten, helping a dying Union colonel by blowing up a bridge just as the colonel passes away, and giving away his coat to a dying soldier.

In this last example, Blondie exchanges the coat for the poncho he wore as Joe and Manco.

Another familiar face is Mario Braga, the guy who gets crushed by a huge wooden barrel in “A Fistful of Dollars”, stabbed in the back by psycho bandit leader Indio in the second film and here having his head smashed on a rock before being run over by a train. He and Sergio must have been really good friends.

Although the story is set against the background of the American Civil War, the main theme of “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” is that of the previous Dollar entries, in which the characters basically keep double-crossing each other over and over and over again until only the good, or in this case the good and the ugly, are left still standing.

It would take another article just to go through the plot but in essence, the three main protagonists are all looking for a cache of money, two-hundred-thousand dollars to be exact, which has been buried in a cemetery called Sad Hill.

You could argue it’s an update of “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre”, only somewhat more violent in the retelling.

I watched the restored extended version that was released on DVD a few years back but to be honest most of the extra sequences don’t really bring much to the table.

The one exception is the sequence in which Tuco takes Blondie to a monastery – Blondie needs to recuperate after Tuco has forced him to trek through the desert without water – and it turns out that Father Ramirez, the head priest, is actually Tuco’s brother.

Apparently, Leone used demo versions of Morricone’s music to choreograph the two sequences at the end of the film, the first in which Tuco frantically runs around Sad Hill cemetery to the strains of The Ecstasy of Gold.

The second scene, in which Blondie, Angel and Tuco face off in a gunfight with the winner taking the money, is accompanied by a Morricone composition called The Trio.

Along with those two compositions, as well as the iconic title track and the unbearably sad Story of a Soldier, I’m surprised no one has yet put on a showing of the film with a live orchestra.

I’d be first in line if that ever happened. In the meantime, I’m just happy to have had the opportunity to see Ennio Morricone in concert twice in the last ten years or so. The man was a bona fide genius, as was Sergio Leone, and “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” is their finest collaboration.

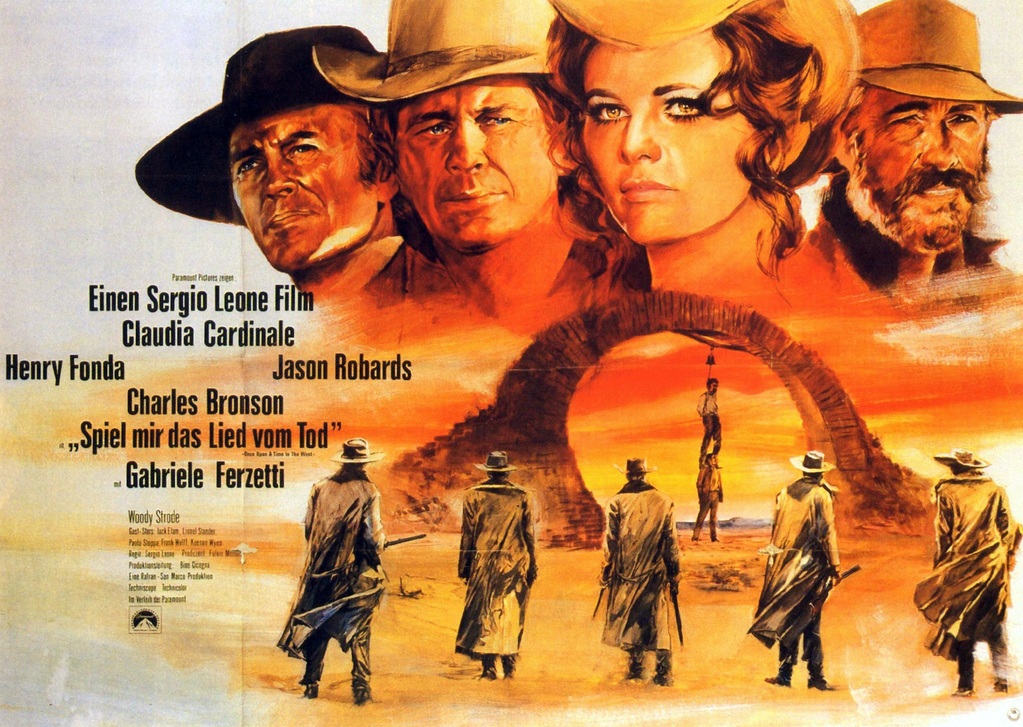

Once Upon A Time in the West (1968)

Sergio Leone finally got the opportunity to make a Western in the country that so inspired his love of the genre with “Once Upon A Time in the West”, released in June 1969.

It’s rightly celebrated for the opening ten-minute sequence in which three gunmen, played by Woody Strode, Jack Elam and Al Mulock wait for a train to arrive in order to kill Charles Bronson, who plays the mysterious Man With A Harmonica, the scene itself an extended riff on a similar setup from “High Noon” in which Sheb Wooley, Lee Van Cleef and Robert J. Wilke wait for the arrival of Frank Miller.

It has been suggested that Leone originally wanted the three gunmen, who all die at the hands of Bronson, to be played by Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach and Lee Van Cleef, the protagonists from “The Good the Bad and the Ugly”, but apparently Eastwood passed. A shame really. It would have made the film even more memorable.

The other celebrated aspect of the film is the unexpected casting of Henry Fonda as a child-killing outlaw by the name of Frank. The incongruity of an actor known for playing morally righteous characters such as Abraham Lincoln and Mister Roberts as a murderous swine bereft of any redeeming qualities whatsoever turns audience expectations well and truly on their head.

Fonda even gets to kick away the crutches from under a crippled railroad magnate, although what with the guy being a rich fat-cat with his own private train and too much money to spend he probably had it coming.

The cast is a mix of contemporary Hollywood faces such as Charles Bronson as the Man With a Harmonica and Jason Robards as the outlaw Cheyenne, along with non-American character actors familiar from other Leone films.

And then there’s Claudia Cardinale, who looks so astoundingly beautiful in the role of lady of the night Jill McBain that words fail us.

The story consists of your basic land-grabbing scenario with a few gunfights and a tale of revenge thrown in to keep the action moving.

To be honest it’s difficult to follow the convoluted plot on occasion, mainly down to the number of versions of the film with different running times that have been issued over the years.

However, there are some great set-pieces in the film, especially the sequence early on when Claudia arrives at the town of Sweetwater by train to find her intended husband is not there to meet her, unaware he has been murdered by Frank.

She walks into the station office at which point the camera rises above the building to the strains of Ennio Morricone’s magnificent theme music, the strings swelling in volume as the town of Sweetwater is revealed in all its glory.

As with “The Good the Bad and the Ugly”, Morricone pre-recorded some of the soundtrack against which Leone then choreographed the live action during principal photography.

Leone overtly borrows from other Westerns like a kid given free rein in a candy shop, referencing classics such as “The Searchers”, “Shane” and “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” along the way.

It looks fantastic on the big screen and, along with the casting against type of Henry Fonda, the wonderful score by the always-reliable Ennio Morricone and the sheer gall of Leone in shooting some of the movie in the hallowed John Ford country of Monument Valley, this is a film we have no problem in recommending to all fans of the Western.

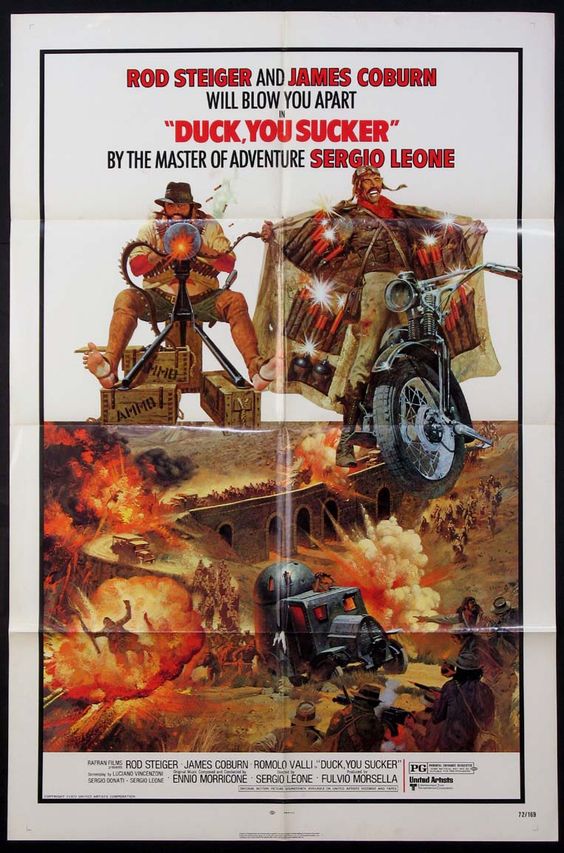

Duck, You Sucker!

More of a so-called ‘Zapata’ Western, a sub-genre of the spaghetti Western form in which the story revolves around a Mexican revolutionary figure and their relationship with a white American character, “Duck, You Sucker!” (aka “A Fistful of Dynamite” / “Once Upon A Time… The Revolution”), released in October 1971, would be Sergio Leone’s last cinematic foray into the form that made his name, as well as – sadly – his penultimate film.

Initially conceived as a low-budget production with Leone as producer and starring Jason Robards and Eli Wallach in the lead roles, the final version ended up with Leone directing instead and the main protagonists played instead by James Coburn as IRA explosives expert John Mallory and Rod Steiger as Mexican bandido Juan Miranda.

The film, which runs for over two-and-a-half hours in its restored form, takes place during the revolution-torn era of Mexico in 1913. The sequence at the beginning establishes Juan Miranda as a character-based along the lines of Tuco from “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”, a morally ambivalent figure torn between love for his family and his disdain for the rich, the latter epitomized by a coachload of the upper crust and pious travelers who fall foul of Juan and his gang.

After a lengthy prologue in which the coach is held up and then stolen by the peasant gang, John Mallory arrives on a motorbike, his presence announced via a series of explosions that precede his appearance through a cloud of dust.

From then on Juan and John are intertwined throughout the rest of the film, each one taking turns to put one over on the other. Juan shoots the tire on John’s bike. John then warns Juan to ‘duck you sucker’ before blowing up the coach.

John jumps on a passing train to escape being pulled into Juan’s plans to rob the National Bank of Mesa Verde. Juan then tricks John into blowing up a church that kills the man who hired him to work at his silver mine.

The non-stop one-upmanship between the two of them is played out against the background of what appears to be a Mexico in a perpetual state of revolution, with each side turning out to be just as bad as the other.

The main villain of the piece is Colonel Gunther Reza, a psychopathic Army commander played by Antoine Saint-John, who spends most of the film trying to outdo Clint Eastwood’s combined body count from all three of Sergio Leone’s Dollar trilogy films and succeeds by a factor of about ten to one.

Eventually, Juan is forced to face up to the reality of a conflict that takes his family from him, though not before he finally gets to rob the Mesa Verde bank.

Naturally, things don’t go as planned, John tricking Juan and his gang into releasing hundreds of political prisoners held in the vaults, as opposed to the copious amounts of gold and silver the bandidos were hoping to liberate instead.

One of the set pieces of the film, reminiscent of the exploding bridge scene in “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”, takes place between Reza and his men and the remnants of the peasant revolutionary forces.

John and Juan defeat Reza and the Federales by firing on them and forcing the soldiers to take cover beneath a stone bridge which John has wired with explosives, blowing most of the enemy to kingdom come.

The film ends in another spectacular confrontation featuring a train crash between the opposing sides in which John dies at the hands of Reza, Juan machine-gunning his nemesis to death and then watching helplessly as John uniquely organizes his own funeral by blowing himself up.

“Duck, You Sucker!” finds Leone in seriously political mode, the opening credits quoting Mao Tse Tung’s message that ‘the revolution is an act of violence”, a message that the director reinforces whenever he can throughout the film.

The occasional light and humorous moments that Leone would insert on occasion to lighten the mood in his Dollar Trilogy are few and far between here.

One that does stick in the mind, however, is when Steiger flexes his hands to indicate stress, a gesture he apparently picked up after watching Leone offset. The film is also noteworthy in that most of the non-American actors deliver their dialogue in English which in turn means that the audience is less distracted than usual when watching a movie in which everyone apart from the main characters is obviously dubbed.

After a slow start, there’s plenty of action to help move the story along and of course, it is blessed with yet another wonderful score by the maestro himself, Ennio Morricone.

Steiger is impressive in a role originally slated for Eli Wallach, stealing the film in the process. James Coburn, on the other hand, is weighed down by having to play an Irishman, his accent on a par with his attempt to sound like an Australian in “The Great Escape”.

Not the most popular Leone Western at the box-office, “Duck, You Sucker!” is still worth viewing if you’ve yet to see it. If you can get hold of the restored version, which was released on DVD a few years back under the title “A Fistful of Dynamite”.

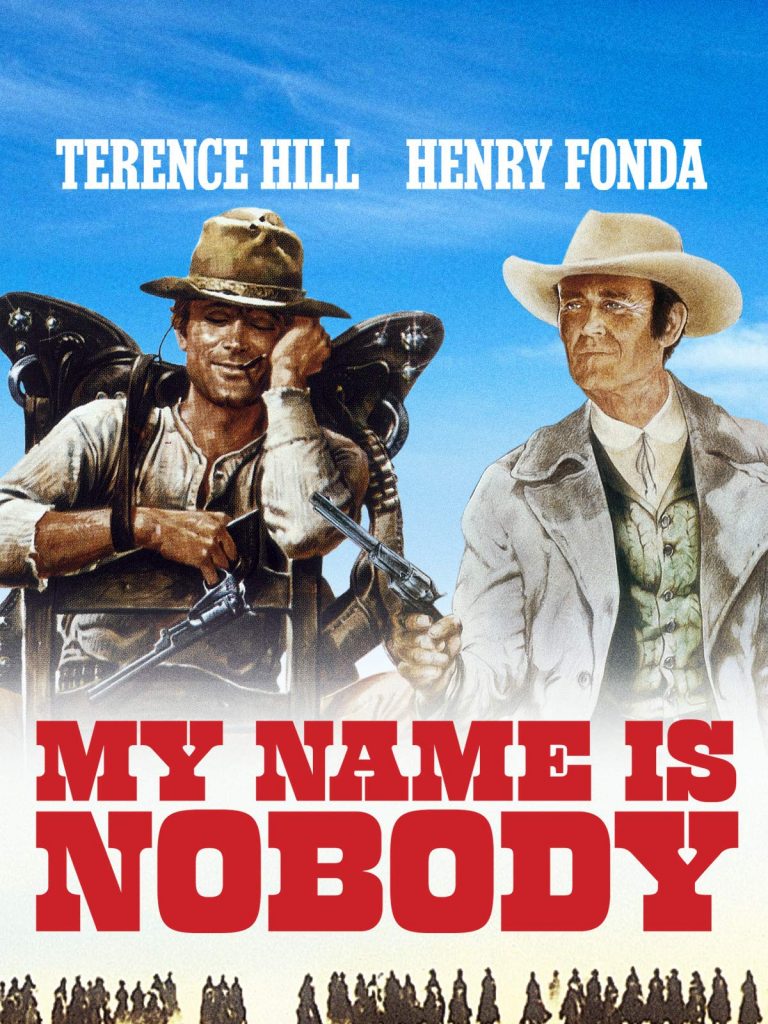

My Name is Nobody (1973)

Direction of “My Name is Nobody” is attributed to Tonino Valerii with Leone receiving a credit for the story based upon his idea.

Leone, however, supposedly contributed a number of scenes by forming a second unit when it became clear the film was running over schedule.

There is some confusion as to which sequences Leone directed himself but there seems to be a consensus it was mainly the scenes shot in Europe.

The bulk of principal photography took place in America which explains why the film features a number of Stateside actors including Henry Fonda, this time playing a ‘good guy’ as gunfighter Jack Beauregard, Geoffrey Lewis as the leader of the Wild Bunch and cameos from Leo Gordon, R.G. Armstrong and Stephen Kanaly.

The film itself is classified as a comedy Western, mainly due to the presence of Italian actor Mario Girotti aka Terence Hill, famous in his home country for a series of comedies he appeared in with Carlo Pedersoli aka Bud Spencer including “My Name is Trinity”, “Two Missionaries” and “Watch Out, We’re Mad!” Whilst not setting the box office alight in America, “My Name is Nobody” did great business in Europe where the Hill / Spencer films enjoyed huge popularity.

Even though not strictly a Sergio Leone film, there are a number of sequences that call to mind his directorial style, in particular, the almost dialogue-free scene at the beginning in which Beauregard guns down three killers who have cornered him in a barbershop.

The film also features yet another hugely enjoyable score courtesy of the maestro Ennio Morricone.

Leone would only get around to making one more movie, the gangster epic “Once Upon A Time in America”, released in 1984, before dying of a heart attack at the age of sixty in 1989.

He was a hugely influential figure for a number of directors, in particular, Quentin Tarantino, whose most recent offering is entitled “Once Upon A Time in Hollywood”. It’s therefore fitting to leave the last word on Leone to Tarantino himself.

This is what he had to say about “Once Upon A Time in the West”:

“I would go even as far as to say that [Leone] is the greatest combination of a complete film stylist, where he creates his own world, and storyteller. Those two are almost never married. To be as great a stylist as he is and create this operatic world, and to do this inside a genre, and to pay attention to the rules of the genre, while breaking the rules all the time — he is delivering you a wonderful Western”