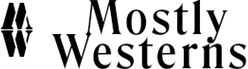

One-Eyed Jacks (1961)

To label “One-Eyed Jacks” as a troubled production would be an understatement.

This article includes affiliate links. If you choose to purchase any of the products we’ve discussed in this article, we may receive a small commission at no extra cost

A number of writers, including Sam Peckinpah, worked on the script which was based on the novel “The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones” by author Charles Neider, a fictional representation of the story of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

The star of the film, Marlon Brando, took on the role of producer and hired Stanley Kubrick to direct only to replace him at the eleventh hour and take on directing duties himself.

Brando’s original cut supposedly came in at over five hours before the movie was taken away from him by Paramount Studios. The film eventually came in millions of dollars over budget and over schedule and made a loss at the box office.

Yet. This film looks absolutely ravishing and it’s a crime that most people these days will never get the chance to see it where it belongs which of course is up there on the big screen.

Cinematographer Charles Lang was Oscar nominated for his work, capturing the landscape in and around the Monterey Peninsula in lush VistaVision colour, this being the last Hollywood film to use that particular format.

Brando was quite astute when it came to casting, peppering the supporting roles with veteran Western actors such as Ben Johnson, Slim Pickens, Katy Jurado, Hank Worden and John Dierkes.

Karl Malden is at his sadistic best as Dad Longworth, Brando’s former partner-in-crime turned sheriff which is lucky seeing as Brando indulges his own penchant for getting a damned good sado-masochistic thrashing (see “On the Waterfront’, “The Wild Ones” and “The Chase”) when Dad ties him to a horse rail and gets it on with a whip.

Brando is also still in thrall to the Method which means it’s a good idea to maybe turn on the subtitles if you happen to have this film on DVD.

Nevertheless, “One-Eyed Jacks” is an interesting and visually spectacular take on the Pat Garrett / Billy the Kid story that has stood the test of time very well.

It’s also the only film Marlon Brando ever directed which makes it a curio in itself. Peckinpah apparently used some of the material from the script he wrote for Brando in his own film version of the story, “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid”, which he directed in 1973.

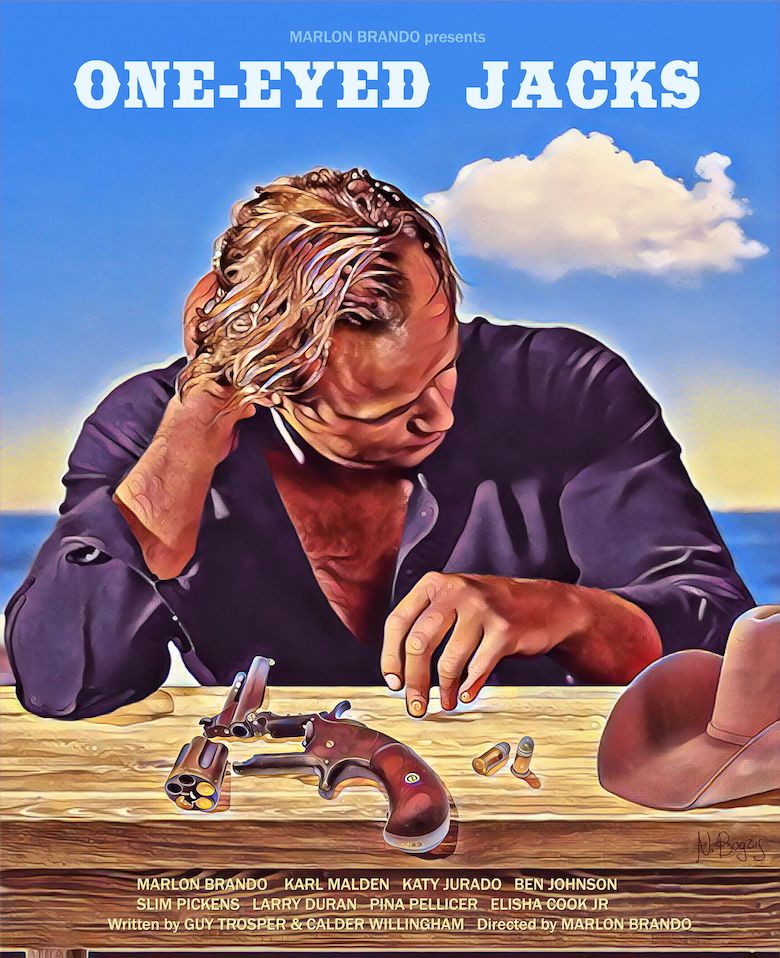

Hombre (1967)

It was only after taking another look at “Hombre” that I belatedly appreciated how much it resembles “Stagecoach” in terms of both narrative and characters.

There are seven assorted travellers in both films with Fredric March, as corrupt Indian agent Alex Favor, closely resembling corrupt banker Gatewood, as played by Berton Churchill in “Stagecoach” whilst Martin Balsam takes on Andy Devine’s role as good guy stagecoach driver Henry Mendez.

In the Ford movie the Apaches posed a threat outside of the vehicle, whilst in “Hombre” the Apache actually rides inside the stagecoach in the guise of the main character John Russell, as played by Paul Newman.

This state of affairs doesn’t last too long though, Favor insisting that Russell sit on top of the coach in order not to offend the female passengers.

The twist in “Hombre” is that Russell is actually a white man raised by the Apaches. Having lived with them he has the requisite skills to help the other travellers when trouble comes their way, even though they hold him in disdain.

Based upon the novel by Elmore Leonard, Newman stoically imbues Russell with all of the characteristics that set him apart from most of his fellow passengers, his dialogue reduced to the barest minimum.

Newman’s taciturn portrayal of Russell is in direct contrast to the likes of the aforementioned Fredric March, David Canary as a bigoted thug and Richard Boone as the splendidly named Cicero Grimes, all of whom make the most of their screen time to impress.

It’s also a bit of a surprise to see Diane Cilento, Australian actress and former wife of Sean Connery, playing the lead female role of Jesse, a fiery and independent former manager of the boarding house inherited by Russell.

The actress more than holds her own onscreen opposite the Hollywood stalwarts in the cast.

Despite his antipathy toward his fellow travellers, Russell comes good in the end in a “needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” confrontation with Grimes, the villain meeting his maker but Russell martyring himself in the process.

“Hombre” is considered to be a revisionist Western as opposed to a standard cowboy shoot-em-up, coming across more as a rumination on the subject of racism instead, although it does deliver the action when required.

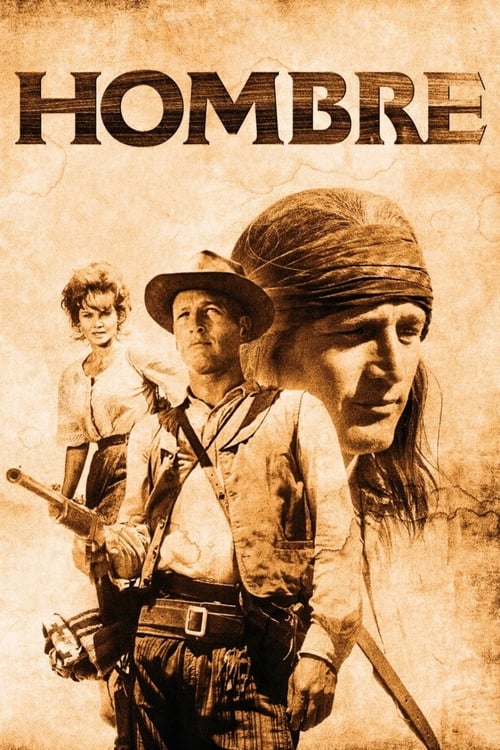

The Glory Guys (1965)

Scripted by Sam Peckinpah, “The Glory Guys” appears to be business as usual when it comes to the maverick filmmaker seeing as directing chores went to someone else instead, in this case, Arnold Laven.

It’s basically a not-too-subtle fictional version of Custer’s last stand, with Andrew Duggan playing a typically arrogant martinet, General McCabe.

Lead actor Tom Tryon as Captain Harrod has nothing but disdain for McCabe due to the latter’s callous attitude towards his own men, a previous encounter with the Sioux resulting in the death of a large number of cavalry soldiers after the General set them up as a decoy.

In the meantime, it’s Harrod’s job to get the new recruits into shape for another bout with the Sioux, recruits that he is well aware McCabe views as expendable.

Into the middle of this stumbles cavalry scout Flow, played by Harve Presnell. He and Harrod end up in a fistfight after finding they’re both vying for the attention of glamourous widow Lou Woddard, played by Senta Berger.

It’s at this point that the comedic aspect of the story comes to the fore, the farcical nature of their knockabout fight making for an uneasy mix with the overall serious tone of the film.

The supporting cast includes Slim Pickens and a pre-stardom James Caan sporting a dodgy ‘Oirish’ accent, yet still winning himself a Golden Globe for New Star of the Year in 1965.

Whilst it would be a push to consider “The Glory Guys” a classic Hollywood Western it does have its moments and it’s worth sticking around for the final battle sequence at the end.

Will Penny (1967)

Written and directed by Tom Gries, “Will Penny” heralds the beginning of Hollywood’s attempt to depict a more authentic version of the West than had previously been depicted on the big screen.

Charlton Heston as Penny is outstanding in the role, portraying the reserved and aging illiterate loner as someone who has left domesticity too late in order to wander the range.

Any Western with a cast list that includes Slim Pickens, Bruce Dern and Ben Johnson is always worth a close look anyway. Lee Major also makes quite an impression as Penny’s younger friend Blue in what was only his third outing on the big screen.

The dialogue is as accurate as it can be to the time the story is set, in this case, Montana in the 1880s. Homilies such as Penny informing the resident trail bully that he’s a weak man who’s likely to “get his plough cleaned” and refusing to take the man on (initially) with the suggestion that “fighting don’t get the work done” are peppered throughout.

Due to the kind act of giving his winter job to a younger man who needs to visit his dying father, Penny finds himself cast adrift with Blue and Dutchy (Anthony Zerbe) who head off to find work for the winter.

Before too long they encounter the deranged Preacher Quilt, played at his deranged best by British actor Donald Pleasance.

In the ensuing confrontation in which both parties claim a dead elk, one of Quilt’s sons is killed in the crossfire which brings down a whole world of hell and damnation on Will and his companions.

To make it even worse one of the surviving siblings of the dead man is played by Bruce Dern at his psychotic best.

After Duchy has to be taken to a local doctor for a wound sustained during the gunfight with Quilt, Penny is hired by rancher Alex (Ben Johnson) to spend the winter guarding the boundaries of his Flat Iron spread.

When Penny arrives at the cabin where he is to spend the winter he encounters a young woman and her son, Catherine (Joan Hackett) and Button (Jon Gries) whom Penny had met previously when looking for a doctor to treat Dutchy, squatting in the cabin.

Deciding to give Catherine and the boy a break and let them stay until winter is over Penny is then bushwhacked by Quilt and the rest of his family.

He is stabbed in the shoulder, stripped of most of his clothing and left to die in the cold. Somehow he manages to crawl back to the shack where Catherine administers his wounds, the two eventually growing close as the cold winter nights set in.

Penny also strikes up a close relationship with Button, but just as things start to turn sentimental with everyone settling into family mode at Christmas in bursts Quilt and his family, the preacher intent on exacting revenge for the killing of his boy.

Just as it looks as though things are going to take a real nasty turn, Blue and Dutchy appear in the nick of time and help Penny to take on the Quilt gang, killing them all in the process.

The film then quite bravely defies audience expectations with Will Penny declaring that he’s left it too late to settle down, riding off at the end with Blue and Dutchy instead of embracing domesticity with Catherine and Button.

A real surprise ending to a film that over the years is now recognised as a classic Western in its own right and one of the best performances Charlton Heston ever gave.

Trivia note: Tom Gries wrote and directed an episode of the TV show “The Westerner” a few years before entitled “Going Home” which served as the template for “Will Penny”.

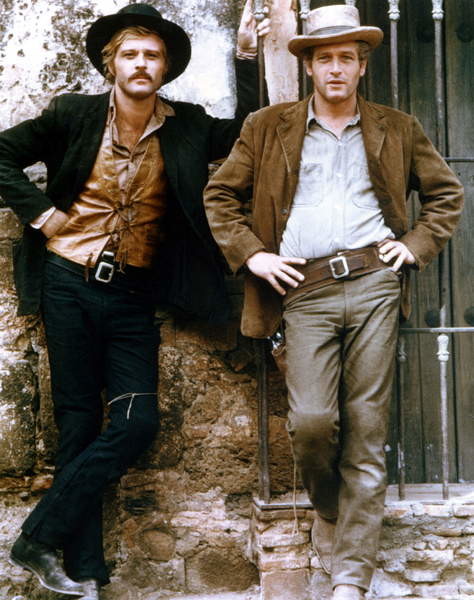

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Directed by George Roy Hill and released at the tail end of the 1960s, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” is a curious mix of action-packed episodes of derring-do and death interspersed with anachronistic contemporary dialogue and a musical interlude that to this day still divides fans and critics alike.

Apart from the pairing of Paul Newman and Robert Redford as Butch and the Kid, plus a memorable soundtrack by the late great Burt Bacharach, the main thing the film has going for it is a wonderfully funny screenplay by William Goldman which makes the viewing of the film a pleasure from start to finish even after all these years.

A short film of the exploits of Butch and his gang plays over the credits, foreshadowing some of the events played out later, after which the audience is informed that “Most of what follows is true”.

The movie remains in sepia tone as Butch cases a local bank and Sundance engages in a card game during which he is accused of cheating before the film finally bursts into full colour.

When Butch arrives at the Hole in the Wall gangs hideout with the Kid he finds his leadership challenged by a very large gang member known as Harvey (Ted Cassidy), a situation Butch de-escalates with a well-aimed kick to Harvey’s cojones.

Taking up Harvey’s suggestion that they rob the Pacific Flyer train the gang do just that, Butch and the Kid celebrating by getting drunk whilst being given a glimpse of the future with the advent of the bicycle.

Butch turns up at the cabin of teacher Etta Place, the girlfriend of the Kid, with Butch, Etta and the bike getting their own sequence in a rendition of “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head”.

After an attempt to rob the Pacific Flyer again is interrupted by the arrival of a posse of railroad men turn up and start killing the gang, Butch and the Kid ride off and double back into town but the posse stays on their trail.

In an attempt to try and go straight Butch and the Kid make a call on an old friend, Sheriff Ray Bledsoe (Jeff Corey) who informs them that they will eventually die bloody and all they can choose is where.

The chase continues and eventually the two outlaws find themselves in a dilemma – either surrender or jump from a cliff into a raging river.

It’s at this point that Sundance reveals that he can’t swim to which a laughing Butch informs him that “the fall will probably kill ya!”.

They then make their way back to Etta’s cabin where she informs them that E.P Harriman of the Union Pacific Railroad has hired a team of professional manhunters lead by a certain Joe Lefors to track down and kill them.

The three of them take off for Bolivia which is a cue for another musical interlude filmed in sepia as they make their way south.

Sundance is not too impressed when they finally arrive at their destination, Butch telling Etta he’ll feel better once he’s robbed a couple of banks.

With the help of Etta the two men learn enough Spanish to successfully start liberating money from the local banks, shown in a montage against which another musical interlude courtesy of Mr. Bacharach plays in the background.

Celebrating their return to a successful life of crime Butch suddenly spots Joe Lefors, recognising him by his distinctive straw hat.

They therefore decide to go straight, signing up with foreman Percy Garris (Strother Martin in a short cameo) as payroll guards.

On their very first outing Garris is shot by Mexican bandits, Butch then being forced to shoot them in turn to retrieve the stolen money. Surveying the corpses of the dead bandits Sundance states “Well, we’ve gone straight. What do we try now?”

Having already declared that she would not hang around and watch them die Etta leaves for home whilst Butch and Sundance stay on in Bolivia.

Riding into a small town the infamous “Yanquis Bandidos” are recognised and within moments the local law sends for backup from the Federales.

The two outlaws are forced to take cover in a cantina, belatedly realising they’ve left their ammunition outside. Butch runs out to retrieve more bullets whilst Sundance covers for him but both end up wounded, Butch taking a bullet in the back and Sundance suffering multiple wounds as they retreat back to the cantina.

Not realising that they are now surrounded the two men discuss the possibility of making a run for Australia once they extricate themselves from the mess they’re in, Butch telling his companion he’ll finally get the opportunity to learn how to swim.

They then make one final break for freedom, only to walk into a wall of gunfire that ends their Bolivian adventure once and for all.

Reviews were mixed when “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” was first released but it still went on to become the biggest box-office hit of the year.

Bacharach, Goldman and cinematographer Conrad Hall won Oscars and the popular screen partnership of Newman and Redford went on to reunite with director George Roy Hill on the “The Sting”, released in 1973.

Trivia notes: Keep your eyes peeled for a very young Sam Elliott as card player # 2 in the early card playing sequence, Sam going on of course to eventually marry actress Katherine Ross. Also, the film is credited with being the inspiration for the popular TV Western series “Alias Smith and Jones” which aired on American TV in January 1971.