When it comes to songs being sung over the credits of any John Wayne Western then the number one spot goes to the Sons of the Pioneers singing the theme to The Searchers.

After that maybe El Dorado and True Grit (great music, not so hot lyrics) tying for second place. Johnny Horton singing North to Alaska isn’t too bad either, although the film doesn’t really deserve a good theme tune of any kind.

I’m sure you John Wayne theme music fans will come up with a few more suggestions on the subject.

Chisum (1970)

Anyway, I liked the opening credits and graphics to this film, even if the title song is a bit cheesy and I like the way the credits finally settle on the iconic image of Chisum surveying all he owns from a hilltop astride his horse. I feel this is definitely where director Andrew McLaglen’s aptitude for capturing the landscape of the West pays off in spades. To my mind the cinematography is one of the best thing about the whole film.

The story comes across as being a bit convoluted and in some ways unnecessarily over-complex. Rammed into the middle of a plot in which villainous Forrest Tucker starts to take over the whole town, we have the story of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid thrown in for good measure.

Kevin Costner managed just fine using the first part of the story in Open Range and I think Chisum would have worked better if it had left out the Billy the Kid stuff, particularly as Sam Peckinpah delivered a more thoughtful appraisal of the Pat Garrett / Billy the Kid story a few years later.

I have written elsewhere that Andrew McLaglen mentioned he was filming Chisum while Peckinpah was making Pat Garrett but the release dates of the two films don’t match so it’s quite possible Andrew was talking about one of his later films instead, Cahill US Marshall maybe.

There doesn’t appear to be any suggestion of romance for Duke / Chisum in this film like there was in his previous Western, The Undefeated, so it’s obvious Wayne has finally been put out to pasture female-relationship wise – although I’d best take another look at Rooster Cogburn before calling quits on Duke’s on-screen love life.

He’s now definitely more the benign uncle to his niece rather than the farmyard rooster of yore, which is probably why Wayne’s performance is one of his most bad-tempered and uncompromising to date – True Grit notwithstanding.

The film is also a bit slower then I remembered and the song that suddenly erupts on the soundtrack in the middle of the film – Settling Down, sung by Merle Haggard doing his best Glen Campbell impression – just doesn’t work, coming across as an attempt to mirror the use of Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (not sure that really worked either if I’m honest).

Having said all of this I still maintain it’s the best of the Wayne / McLaglen Westerns – the climactic fist-fight between Duke and Forrest Tucker is everything you would want in a John Wayne cowboy film so on the whole a very respectable late career Duke Western that delivers the goods.

It should be pointed out that it was on this film Wayne agreed to record an album of poems written by one of his co-stars, John Mitchum (brother of Robert). The result, released in 1973, was called America, Why I Love Her. Now, whilst I don’t want to give the impression I’m not exactly a fan of the album, I would like to say how grateful I feel that Duke decided to recite rather than sing the poems – it did go on to win a Grammy after all so credit where credit’s due. So, all together now:

‘You ask me why I love her? Well, give me time and I’ll explain.

Have you ever seen a Kansas sunset or an Arizona rain?

Have you drifted on a bayou down Louisiana way?

Have you watched the cold fog drifting over San Francisco Bay?’

I can honestly say that brings a tear to my eye – in more ways than one.

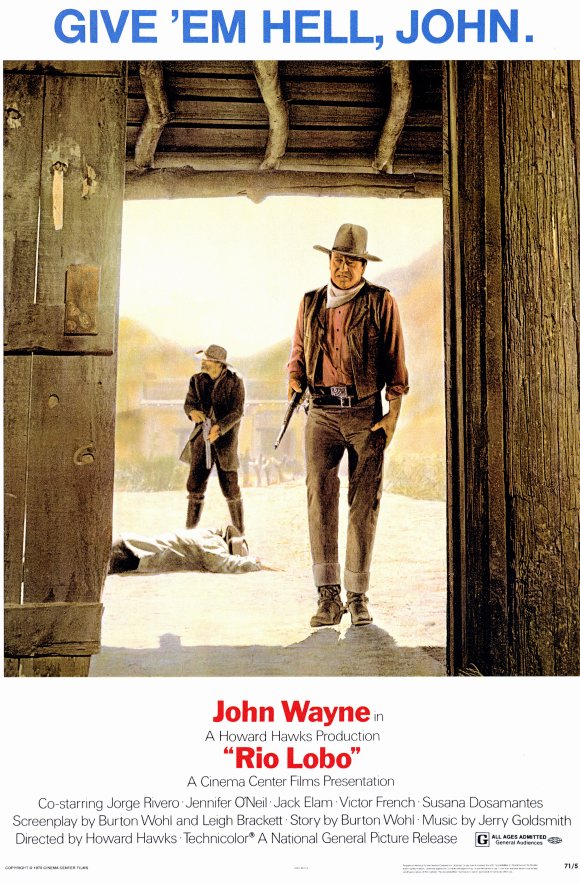

Rio Lobo (1970)

This is not only the last film John Wayne and director Howard Hawks made together, it was also the last film Hawks would ever make, dying seven years later in 1977.

He ran a close second to Ford when it came to making classic Westerns with Wayne, and very nearly outdid Ford with Rio Bravo, which only just slides in behind The Searchers as best Duke Western ever. Red River and El Dorado are not to be sneezed at either. I guess it’s inevitable that late career movies for a director and actor tend not to be as good as their earlier efforts, but Rio Lobo definitely has its moments, even if most of those moments derive from Rio Bravo.

Just like The Undefeated the film starts in Civil War territory, the opening sequence an extended train heist fashioned along the lines of The War Wagon. This time however it’s Wayne and his army companions who are on the losing end, with Duke spending the rest of the film – post-Civil War – hunting down the Union soldier who betrayed the whereabouts of the train, which was carrying gold bullion – what else? – to the Confederate army.

Then along comes Jennifer O’Neill and nearly ruins the whole thing. Her lack of acting talent is such that her inability to convey the characteristics of what has become known as the ‘Hawksian’ woman ends up making Charlene Holt in El Dorado look like Meryl Streep.

Luckily cowboy stalwarts such as Jack Elam, Jim Davis and Hank Worden ride to the rescue and serve to erase O’Neill’s contribution from the collective memory. I even caught sight of the ever reliable Cliff Robertson in there, playing what I think were two separate characters – he must have needed the money.

I note the irony of the presence in the film of David Huddleston, playing the town dentist. A couple of years later he appeared as the mayor of Rock Ridge in Blazing Saddles, a film I personally hold responsible for single-handedly sounding the final death knell for the Hollywood Western.

If there is a God then there should have been a scene in Rio Lobos in which Duke would have punched his lights out but, as the memorable line from The Alamo states, when it comes to the Almighty, his ‘stick don’t float that way’. Apologies to any relatives of the recently deceased Mr Huddleston if you happen to be reading this article right now

The script is actually quite good, which isn’t surprising seeing as it was co-written by Leigh Bracket of The Big Sleep and Rio Bravo fame. Also, carrying on from where Chisum left off, Wayne is left high and dry once more in the female relationship stakes, christened as ‘comfortable’ by one of his lady co-stars as his on-screen love life continues to bite the dust.

The similarities between Rio Lobo and Rio Bravo – and El Dorado for that matter – are too numerous to list here but the most obvious is the exchange of hostages at the end of the film, mirroring that of Dean Martin and Claude Akins in the earlier film.

Add to that the fact Walter Brennan must have left quite a lot of the dynamite hanging around that he used in Rio Bravo and I’d say someone somewhere needs to file a plagiarism suit.

One final thought on Rio Lobo. The most significant aspect of this production isn’t actually the film itself, but the publicity campaign that followed. The poster for the film exhorts our hero to ‘Give Em’ Hell, John’, totally ignoring the fact that Duke plays a character called Cord McNally. I’d say this is the defining moment when Wayne and his onscreen characters finally melded into one in the eye of both the the movie-going audience and the film industry itself.

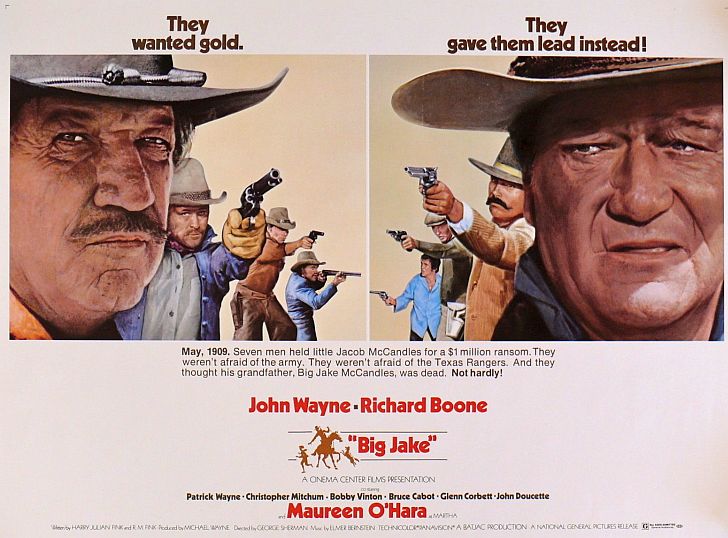

Big Jake (1971)

I confess that I have written elsewhere that a Western must be set somewhere between the end of the Civil War and the late 1890s in order to be considered a proper cowboy film. On reflection that’s not quite correct.

The Wild Bunch is set in 1913 but it still qualifies as a wonderful example of the genre. So, seeing as Big Jake is set in 1909 it’s still very much a Western, and a surprisingly good one in Wayne’s late career period.

First of all though, let’s play a little game.

Imagine you’re going to oversee the production of a John Wayne Western. What components do you need to throw into the mix to make it a classic Duke cowboy film?

First off you hire yourself a director who has worked with Wayne previously. Step forward George Sherman, who directed at least 9 of Duke’s early period Republic films as well as producing The Comancheros. Don’t forget a rousing soundtrack by that old stalwart, Elmer Bernstein.

Gather together a collection of members of both the Ford and Wayne stock acting company looking for what might possibly be their last payday – Bruce Cabot, John Agar (who has the good sense to get himself killed in the first reel), Harry Carey Jr., Glenn Corbett, Jim Davis, Hank Worden, Chuck Roberson, Richard Boone and last but certainly not least Miss Maureen O’Hara in her last onscreen role with Duke.

Don’t forget to surround our hero with members of his family – Patrick and his youngest son Ethan – then pull in a script by the writers of the Dirty Harry film to give it a 70s gratuitous acts of violence Peckinpah vibe for contemporary audiences.

Reference other Westerns made around that time by taking a relatively well-known character actor such as Harry Carey Jr. and cast him against type as a merciless child killer just like they did with Henry Fonda in Once Upon a Time in the West, open the film with a montage of black and white images as used in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, then mirror the opening sequence of The Wild Bunch with a senseless bloodbath just to kick things off in the right gear.

Oh yes, one other thing. Get Duke to say ‘That’ll be the day’ and ‘Let’s go home’ for all those Searchers fans out there and the end result is a bona fide honest-to-goodness classic John Wayne Western that stands comparison with the best of them.

The main plot revolves around Duke trying to rescue his grandson who has been kidnapped by a group of dastardly outlaws lead by Richard Boone.

Maureen O’Hara, cast yet again as Wayne’s estranged wife, hires her husband to help retrieve their kidnapped grandson. Baulking at the offer of help from the Texas Rangers who speed off in their newly acquired jalopies, with Christopher Mitchum playing one of Wayne’s offspring as a low-rent Steve McQueen on a fancy motorbike, Jake catches up with the remnants of the bushwhacked Rangers on his horse then proceeds to hunt down the kidnappers like the mangy dogs that they are.

The moral of the story is that modern progress, in the guise of new-fangled contraptions such as automobiles and motorbikes, can never hope to compete with John Wayne in genuine killing mode.

In short, the old ways are the best. And don’t you forget it, Pilgrim.