John Wayne and director John Ford forged a screen partnership that produced a body of work almost unparalleled in Hollywood history. If either of them had never made any other films they would both still be lauded for having produced some of the most famous and popular movies ever made, the majority of them firmly ensconced within the Western genre.

Strictly speaking, Wayne appeared in a number of late silent films directed by John Ford, including “Hangman’s House”, “Four Sons” and “Mother Machree”, but he is only credited as being an extra. Wayne also had a speaking part in a small role as a navy cadet in Ford’s 1920 early talkie “Salute”, but he goes uncredited in the cast list.

For Wayne, it all began, of course, with “Stagecoach” in 1939, the actor having spent the intervening years after the box-office failure of “The Big Trail” in 1930 churning out a series of low-budget cowboy and adventure serials and five-reelers for studios such as Columbia, Warner Brothers, Lone Star and Republic.

Ford, however, had been on a roll ever since the success of the silent Western epic “The Iron Horse” in 1924, the box-office winner making the director almost a household name from then on.

By the time Ford and Wayne teamed up on “Stagecoach”, the director already had one Best Director Academy Award under his belt with “The Informer”, released in 1935, and would go on to win another record-breaking three Best Director Oscars with “The Grapes of Wrath”, “How Green Was My Valley” and “The Quiet Man”.

In all they collaborated on thirteen full-length feature films from 1939 to 1963, Wayne also making a short cameo appearance in the Civil War sequence for “How the West Was Won”, the only part of the film directed by Ford.

Rather than review the films chronologically, we thought we’d list them by order of preference as we have done for previous other articles featuring John Wayne films by director.

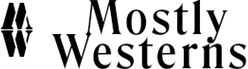

How the West Was Won (1962)

How the West Was Won (1962)

Wayne only appears for about two minutes in a film that runs for approximately 2 hours and 40 minutes this in epic Cinerama Western.

With a cast that also included a preponderance of the great and the good of the Hollywood actors of the time such as James Stewart, Henry Fonda, Gregory Peck, Carroll Baker and Debbie Reynolds, “How the West Was Won” is, in box-office terms, the most successful film Duke ever appeared in.

On a budget of just over fourteen -million-dollars, the film took a whopping fifty-million in rentals worldwide which, allowing for inflation, equates to about four-hundred-and-fifty million in today’s money.

Wayne plays General Sherman with co-star Henry Morgan as General Ulysses S. Grant.

As a lot of Duke fans know, this wasn’t the first time Wayne had played the famed Union general. He appeared in a cameo role a few years before in a two-part episode of the “Wagon Train” TV series, also directed by Ford, and was credited in the cast list as Michael Morris.

Wayne’s screen time in “How the West Was Won” is taken up convincing General Grant that he shouldn’t resign his command once the battle of Shiloh is over. While all this is going on, George Peppard as a Union soldier and Russ Tamblyn as a Rebel deserter watch from the sidelines. Tamblyn then attempts to shoot Grant, forcing Peppard to kill his new friend with a bayonet. Hannibal Smith gutting Tom Thumb. Now that’s something you don’t get to see every day.

John Ford manages to sneak in a couple of his stock company members, Andy Devine and Ken Curtis, into the film as well as a graveside conversing-with-the-dead scene reminiscent of other Ford movies such as “Young Mr. Lincoln” and “My Darling Clementine”. There’s never really enough room for subtlety in these huge overblown Hollywood extravaganzas but Ford acquits himself very well, as does Wayne in his all-too-short cameo.

Trivia note: JW donated a brief shot of Mexican soldiers from “The Alamo” for inclusion in “How the West Was Won”.

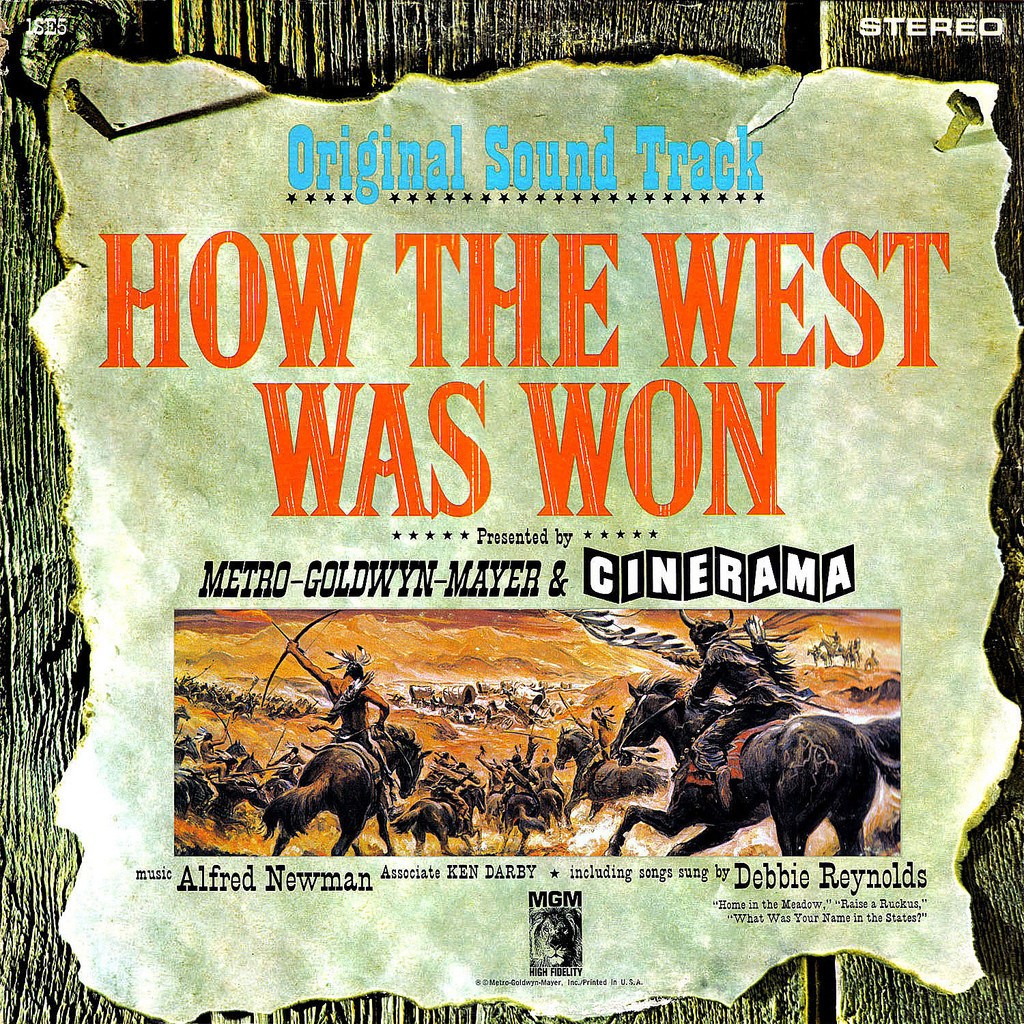

The Wings of Eagles (1957)

This isn’t really a war film per se, more of a bio-pic about the Navy aviator turned screenwriter turned Naval commander, Frank ‘Spig’ Wead.

This isn’t really a war film per se, more of a bio-pic about the Navy aviator turned screenwriter turned Naval commander, Frank ‘Spig’ Wead.

He and Ford had worked together on “Air Mail” in 1932 and “They Were Expendable” in 1946. Wead also wrote screenplays for quite a few other wars and air-based melodramas such as “Ceiling Zero”, “Test Pilot” and “Dive Bomber”. At some point Ford must have decided Spig’s life story was eventful enough to turn into a film and this is the result.

The movie starts with an extended slapstick sequence in which Spig crashes his plane into an admiral’s garden party, this being the most upbeat section of the film before things start to get really serious. He ends up crippled after accidentally falling down the stairs, his pal “Jughead” Carson, played by Dan Dailey, inventing a new type of therapy in which he miraculously cures Spig’s broken neck by strumming a banjo and singing “I’m gonna move that toe”.

Maureen O’Hara’s role as Wayne’s wife is a bit thankless, required to come out of the shadows every now and then for most of the film to indicate the on-off nature of her relationship with Wayne, her character just kind of disappearing before the end of the film.

Portraying a man who is physically weak is quite a departure for Duke. It’s also notable that as his character ages the makeup starts to come off until we see something that doesn’t happen very often in a JW film – he takes his wig off as well.

There’s quite an entertaining sequence in which Spig meets the famous Hollywood director John Dodge, with Ward Bond lording it up as a thinly disguised portrayal of Ford himself. We know he’s supposed to be John Ford because he has a portrait of Harry Carey Senior on his office wall and a big model of a stagecoach on the table.

About three-quarters of the way into the film Spig hears on the radio about the attack on Pearl Harbor, so he drops the scriptwriting and somehow ends up seeing action in the Pacific. Spig drops the scriptwriting and somehow ends up seeing action in the Pacific.

The ending is quite poignant, with Spig invalided out of the navy due to ill health. The final scene in which an old-looking Wayne is hoisted across the water from his battleship to a cruiser that will take him home almost brings tears to your eyes.

Not exactly a classic film for either Wayne or Ford but as a rumination on ageing and mortality it’s worth taking a look at.

Donovan’s Reef (1963)

By the time they made their last film together, both actor and director had worked with each other for nearly two-and-a-half decades. It’s therefore inevitable that the occasional lesser effort will surface every now and then, and “Donovan’s Reef” falls into that category.

By the time they made their last film together, both actor and director had worked with each other for nearly two-and-a-half decades. It’s therefore inevitable that the occasional lesser effort will surface every now and then, and “Donovan’s Reef” falls into that category.

The story is rather slim, to say the least with Wayne as “Guns” Donovan and Lee Marvin as “Boots” Gilhooley honouring a long-held tradition of kicking the stuffing out of each other on the occasion of their shared birthday.

It’s not an unwatchable film by any means and the fact that the year before Wayne and Ford partnered on the classic Western “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” indicates that, given a good story and decent budget, late Wayne / Ford films could compete with the best that Hollywood had to offer at the time.

It’s just that, with “Donovan’s Reef”, Wayne appears to be going through the motions in a part that he could have played with his eyes closed. Add to this he was by then about twenty-two years older than his love interest opposite number, Elizabeth Allen, and the cracks are starting to show.

Having said that, Dorothy Lamour, who plays Lee Marvin’s on-off girlfriend, was at least ten years older than Marvin at the time, so the film should be applauded for being an exercise in equal opportunity when it comes to inappropriately aged elder partners

“Donovan’s Reef” was shot mainly on location in Hawaii, and Ford took the opportunity to sail his beloved yacht “Araner” over from California to guest star in the film. There’s one laugh-out loud moment when Elizabeth Allen as a snooty Bostonian company board member sits in the back of a jeep as it races down the road.

The jeep hits a bump that sends her up in the air whilst the vehicle continues on its way, unceremoniously dumping her – or more accurately her stand-in – on her backside in the middle of the street. There’s also an amusing reference to contemporary culture in which a group of small children breaks out into an impromptu demonstration of the twist dance craze of the time, but it’s not enough to push the film in the direction of classic status.

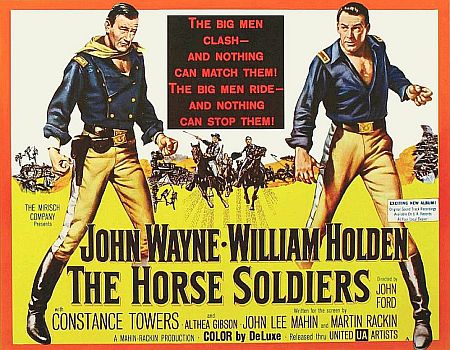

The Horse Soldiers (1959)

“The Horse Soldiers”, a big screen Civil War saga released January 10th 1960, boasted two of the most popular stars of the time, John Wayne (naturally), and William Holden, JW working with director John Ford for the first time since their collaboration on the classic Western “The Searchers”.

“The Horse Soldiers”, a big screen Civil War saga released January 10th 1960, boasted two of the most popular stars of the time, John Wayne (naturally), and William Holden, JW working with director John Ford for the first time since their collaboration on the classic Western “The Searchers”.

The movie also features a number of Ford stock company actors including Ken Curtis, Anna Lee and Hank Worden as Deacon Clump, the latter seemingly rehearsing his part as Parson for his next Wayne movie “The Alamo”. Strother Martin also pops up as a Reb deserter in the first of six appearances he made in JW films.

The story, apparently based on a real incident, involves Wayne, as Col. John Marlowe, taking a brigade of Union soldiers deep into Johnny Reb territory in order to carry out an attack on a town that supplies the Confederate army at Vicksburg.

It’s a mission impossible operation with no guarantee of getting back in one piece and Holden, playing regimental surgeon Major Hank Kendall, is at loggerheads with Marlowe almost from the moment they meet, setting the story up for them to eventually start punching each other senseless.

Easy on the eye Constance Towers, as Southern Belle Hannah Hunter, eavesdrops on Marlowe discussing the plans for his brigade.

Easy on the eye Constance Towers, as Southern Belle Hannah Hunter, eavesdrops on Marlowe discussing the plans for his brigade.

When she is discovered by Holden, Marlowe is forced to take Ms. Hunter and her black maid Lukey, played by tennis champion Althea Gibson, along for the ride. Hunter is not that enamoured of Marlowe at first but of course eventually falls for JWs rough mix of wit, charm and charisma, even though he’s operating in ornery and cantankerous mode for most of the film.

It takes almost exactly one hour before the movie finally springs into action but after that, it’s practically non-stop all the way to the end. A band of Confederate soldiers attempts to retake the town from Marlowe and his men which in turn initiates a bloodbath with the Rebs decimated in the main street.

After the battle, Marlowe gets drunk and tells Ms. Hunter that his wife died in a botched operation which explains why he doesn’t like the medical profession.

One of the main problems with the movie is that the chemistry between Wayne and Holden never really comes to life. They do end up squaring off at each other at some point in the film but their encounter doesn’t possess the pugilistic essence of Wayne’s fisticuffs with other actors such as Forrest Tucker in “Chisum” or Victor McLaglen in “The Quiet Man” for example.

As the much-anticipated fistfight is about to kick off their encounter is interrupted by an attack from a group of Confederate cadets, some of them still children, who are bivouacked in a nearby military academy.

Based upon a true incident from the Civil War, it’s one of the best sequences in the film, and an example of how John Ford smuggles relatively unknown American historical events into his work, informing as well as attempting to entertain the audience.

The action and battle sequences are well-staged as you might expect from a Ford film but the climax is basically just a case of the Union soldiers riding across a bridge then blowing it up before the Confederate army catches up with them.

One of the reasons “The Horse Soldiers” ends so abruptly has been put down to the fact that one of the stuntmen was killed during production of the film. After that incident, it has been recorded by a number of writers on Ford that he lost enthusiasm for the whole thing, as the end result would appear to attest to.

It’s the kind of film that grows on you with repeated viewings and it does seem to improve with age. Ford was an authority on the Civil War and Civil War and in “The Horse Soldiers” he highlights, as he does so many times in his films, the notion of Southern manners and nobility versus the perceived lack of grace of those fighting for the Union, so for that alone it’s long due a reappraisal.

The Long Voyage Home (1940)

In the second film that he appeared in for director John Ford, John Wayne plays a fresh-faced Swedish farmer by the name of Olson.

In the second film that he appeared in for director John Ford, John Wayne plays a fresh-faced Swedish farmer by the name of Olson.

It’s the only time that we aware that JW tried using a voice other than his own, attempting a Swedish accent with varying degrees of success. The film boasts an excellent smattering of Ford stock company members, including Barry Fitzgerald, Mildred Natwick, Ward Bond and Arthur Shields, all of whom Wayne went on to work with over a decade later in “The Quiet Man”.

The cast is complemented by British actors Ian Hunter and Wilfrid Lawson, playing respectively a mysteriously broody member of the crew and the ship’s captain.

The film is an ensemble piece based upon a collection of one-act plays by American playwright Eugene O’Neill, and is lauded for the distinctive cinematography of Greg Toland, who is listed on the opening credits next to Ford’s name, utilising a number of deep focus compositions that he would adopt to even greater effect a few years later when working with Orson Welles on “Citizen Kane”.

The plot follows the voyage home to England of a tramp steamer on which various sea-going characters all have their own story to tell.

Some of them come to a sticky end, with Ward Bond copping it early on and Ian Hunter getting shot to pieces by an enemy fighter plane that attacks the ship, which is transporting explosives to England.

In Wayne’s case, he wants to get back to visit his family in Sweden, having sailed the high seas for ten years. Poor young Ole’s efforts to make it home are stymied when he is drugged and shanghaied after his ship finally docks in England.

One of Ole’s older shipmates, Driscoll, played by “Stagecoach” co-star Thomas Mitchell, gets the gang together to help rescue Ole before the ship he’s being held on sails to sea. During the attempt to liberate their sailing companion, Driscoll is knocked unconscious and ends up going down with the ship after it’s torpedoed by a German submarine.

You can tell from this that the film isn’t exactly a barrel of laughs, but if you’ve yet to see it then you’ll appreciate the consummate direction of John Ford and the winsome innocence of Wayne’s character, who finally makes it back to home and hearth in Sweden.

Rio Grande (1950)

This is the film John Ford had to direct for Herbert Yates, the Republic studio head, in order to get Yates to finance “The Quiet Man”.

This is the film John Ford had to direct for Herbert Yates, the Republic studio head, in order to get Yates to finance “The Quiet Man”.

The end result, whilst still a classic Ford / Wayne opus, is probably the weakest of the Ford cavalry trilogy movies. The noble Native American figures that Ford depicted in “Fort Apache” and “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon”, with well-rounded characters and a voice of their own, are here replaced by the nameless ciphers of earlier John Ford films such as “Stagecoach” and “Drums Along the Mohawk”.

In her first movie with Wayne, Maureen O’Hara shines as his estranged wife Kathleen, their marriage having apparently foundered on the basis that her husband fought for the Union during the Civil War whilst Kathleen played the high-falutin’ Southern belle down on the plantation.

To complicate matters further their son, played by Claude Jarman Jr., has been assigned to his father’s outpost. The mother arrives to take her son back home to the land of Dixie, the marital discord that follows serving as a template for the relationship Wayne and O’Hara enjoy in their next film, “The Quiet Man”.

Family dramas aside, “Rio Grande” is nonetheless a good old-fashioned Western action film, even if the political landscape in 1950, the film going into production a couple of weeks before the outbreak of the Korean war, means that certain film writers make the link between the Apache savages and the nasty North Korean adversaries of the time.

The climax of the film has Wayne and his compatriots tracking down a bunch of Apache renegades who have kidnapped a wagonload of children and taken them across the border into Mexico.

Needless to say, our hero wins the day and the frontier is made safe once again, until the next uprising anyway.

Ford shot some of the film in his favourite location, Monument Valley, but unlike “The Searchers” or “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon”, the landscape doesn’t really take on a character of its own.

Wayne’s character is called Kirby Yorke as opposed to Kirby York, the part he played in the earlier Ford film, “Fort Apache”. Assuming they are one and the same character then York / Yorke has been promoted from Captain to a Lieutenant Colonel.

Ben Johnson reprises his role as Tyree from “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon”, seemingly demoted from Sergeant to Trooper status in “Rio Grande”. Ford regular Victor McLaglen reappears as Quincannon, not only promoted from Sergeant in “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon” to Sergeant Major, but also having re-enlisted after retiring from the army in the previous film. Confused? You should be.

One aspect of the film worth noting is the wonderful soundtrack by Victor Young, with the theme for “Rio Grande” recycled a year later for “The Quiet Man” as a piece entitled “My Mother”. On top of that, the film features old favourites such as “I’ll Take You Home Again Kathleen” and “The Girl I Left Behind”.

Trivia note: the working title for “Rio Grande” was actually “Rio Bravo”. According to film writer Joseph McBride, who authored the biography “Searching for John Ford”, the title was dropped due to someone making a legal claim on the name, so instead of “Rio Bravo” we got “Rio Grande” instead.

3 Godfathers (1948)

This is a real gem of a movie, and a great ensemble piece for Wayne, Harry Carey Jr. and Pedro Armenderiz. The film, which should basically be subtitled “The Three Wise Men Go West”, had been filmed a number of times previously, first in 1916 under the same title with Harry Carey Senior in the lead role, then again with Carey and Ford himself directing and released as “Marked Men” in 1919.

This is a real gem of a movie, and a great ensemble piece for Wayne, Harry Carey Jr. and Pedro Armenderiz. The film, which should basically be subtitled “The Three Wise Men Go West”, had been filmed a number of times previously, first in 1916 under the same title with Harry Carey Senior in the lead role, then again with Carey and Ford himself directing and released as “Marked Men” in 1919.

The third attempt was released in 1936 but Ford’s 1948 film is the definitive version. Wayne plays outlaw Robert Marmaduke Sangster Hightower who, along with his two bandit compatriots, the Abilene Kid, played by Harry Carey Jr., and Pedro “Pete” Rocafuerte, played by Pedro Armendariz, stumble upon a dying woman about to give birth while they’re on the run from a local posse.

This time we get Duke in affable mood, one of Ford’s ‘good bad men’ in the mould of the Ringo Kid and modelled on Harry Carey Senior’s Cheyenne Harry character from Ford’s silent period. In fact, it’s almost a continuation of the character Wayne played the year previously in “Angel and the Badman”, Duke’s career at this point in time obviously going through his “baby-holding” period.

It’s less of an action film, however, and more an obvious Biblical parable, with the three outlaws giving up the opportunity to escape from the law in order that the child of the dead mother survives.

Duke eventually delivers the baby to safety just in time for Christmas. And in case the audience still doesn’t get the point he takes the baby to a town called New Jerusalem.

Harry Carey Senior died a year before the film was released and Ford put his son, Harry ‘Dobe’ Carey under contract to his Argosy production company. This was Dobe’s first film for Ford, and he’s quietly impressive as the Abilene Kid.

If you want the lowdown on how Ford treated his new young actor during the filming of “3 Godfathers”, then look no further than Carey’s highly readable book, “Company of Heroes”, in which he recounts how Ford made him suffer during the filming of his death scene which took place in Death Valley.

Despite Ford’s somewhat sadistic treatment of Carey Junior, the director pays a poignant tribute to Harry Carey Senior at the beginning of the movie. He filmed a short scene using Cliff Lyons, who eventually ended up working as a stuntman and helped Wayne with the battle sequences in The Alamo, to double as Dobe’s dad on Carey Senior’s favourite horse, Sonny. The film is ‘Dedicated to Harry Carey, a bright star in the early Western sky’.

Not your typical Wayne cowboy action film, but highly watchable just the same.

Let us know below of any thoughts you might have. Check out our second part of the article on the films John Wayne made with director John Ford.