The Very Best of Clint Eastwood’s Western Movies

This is the 2nd part of the best Clint Eastwood western movies. Catch up with part one.

Joe Kidd (1972)

After the disappointment of Hang ‘Em High and Two Mules for Sister Sara, in which Clint struggled to elevate his Hollywood cowboy persona to the heights he scaled with Sergio Leone in the Dollar trilogy, he thankfully – and finally – made amends with Joe Kidd, directed by veteran Western filmmaker John Sturges.

I’m thinking that Clint finally realised that his acting style was best suited to the “less is more” approach when it came to this movie, something that was aided and abetted with a great script from Elmore Leonard.

Also, in contrast to the occasionally overwrought thespian talents of co-stars such as Robert Duvall and John Saxon, Eastwood brings a much more relaxed and laconic air to his performance, something that was sadly missing from his previous two Western efforts.

Joe Kidd is an out-of-work bounty hunter turned town drunk who finds himself embroiled in a dispute between land-grabbing Frank Harlan, played by Duvall, and a Mexican revolutionary, Luis Chama, played by Saxon.

Harlan puts together a posse to hunt Chama down and offers Kidd a job, which he declines. Then he finds out Chama has attacked his ranch – although how Joe Kidd manages to keep a ranch going with all that boozing is never explained.

He subsequently throws in his lot with Harlan and the fuse is then set for a showdown between all parties concerned.

I remember that when I saw this film back in 1972 an acquaintance told me how delighted he was to see that this was the first Western to correctly show how a bullet can leave a rifle and hit its target before making a sound.

How he knew this I never found out. Sometimes it’s best not to ask.

Anyway, the scene he referred to features a long-range telescopic rifle shootout between one of Harlan’s men and Kidd, with Kidd winning the day on account of he’s the best shot.

He also manages to get the upper hand on another Harlan acolyte, played by Don Stroud, the thug Clint has to hunt down in Coogan’s Bluff.

At the end of that film, he feels sorry for Stroud and offers him a smoke. This time round Clint must have run out of cigarettes and just offers poor old Don a broken neck instead.

At the end of the movie, Clint gets to ram a locomotive through the wall of a saloon, then polishes off what’s left of Harlan’s men in deadly quick-fire Man With No Name style.

He then puts paid to Harlan’s real estate development plans by plugging him as well before handing Chama over to the sheriff, prior to which he punches the sheriff for an earlier infraction of etiquette.

To really rub salt into the wound, he then rides off into the sunset with Chama’s girlfriend.

As I believe the saying goes, “Now that’s what I’m talking’ about”.

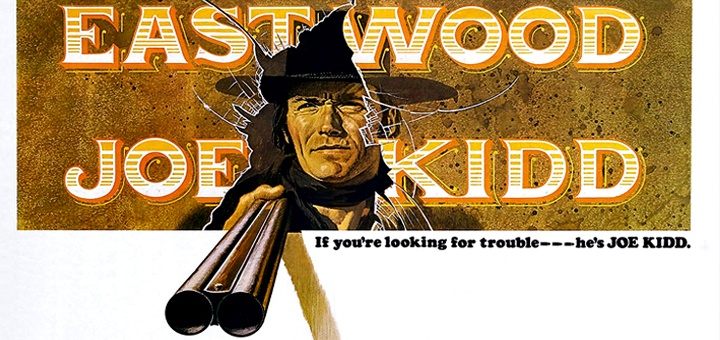

High Plains Drifter (1973)

High Plains Drifter (1973)

Clint finally gets to direct himself in a Western and the result is – well, it’s interesting, to say the least.

He’s just called the Stranger, which is an obvious nod to The Man With No Name.

I’m noticing a pattern in his Westerns whereby Clint always likes to shoot a trio of bad guys just to get things started and this time is no exception.

Within a few minutes of riding into the town of Lago, he offs three gunmen, then starts playing with the moral compass of his character by raping a young woman who was obviously trying to ingratiate herself with him.

I doubt if that kind of behaviour would go down too well in this day and age but, as I’ve had to repeatedly impress upon my faithful readership, it was different times, my friends, different times.

It seems that the townsfolk colluded with a bunch of outlaws in the murder of the previous sheriff, then double-crossed the killers who at some point are going to come back and exact their revenge.

Into the middle of this rides the Stranger, someone the duplicitous denizens of Lago think they can put their trust in, albeit one who tends to kill and rape as and when the mood takes him.

Geoffrey Lewis, an actor with the iciest killer blue eyes to ever grace the screen, makes his first appearance in an Eastwood film as outlaw Stacey Bridges.

Lewis went on to appear in at least another half dozen of Clint’s movies, making him one of the first members of the actor / directors stock acting company.

Paul Brinegar, who played Wishbone in Rawhide, is also along for the ride. That’s what I like about Clint. He never forgets his friends.

Just as in the Dollar trilogy, one party double-crosses the other, Clint implying he’s going to help protect the town from the killer outlaws.

He suggests they start preparing to defend themselves and also to paint the town red, which they eventually do. The Stranger then hightails it out of town and leaves the weak-willed inhabitants of Lago at the mercy of Bridges and the outlaws.

There’s a hint of the supernatural in the story that doesn’t really work for me. The suggestion is that the Stranger has come to avenge the dead sheriff, who was whipped to death by the outlaws whilst the townspeople looked on.

Or maybe the Stranger is the ghost of the dead sheriff. I never could figure it out so I reckon that will have to remain a mystery.

Of course, Clint returns and wipes out Bridges and the boys because that’s what Clint does.

In the final scene, he rides past a graveyard where the sheriff was buried and there’s a couple of graves dedicated to Sergio Leone and Don Siegel, which I thought was a nice touch.

It’s quite a stylish film and Clint certainly knows how to handle himself behind as well as in front of the camera, but the ghost stuff kind of left me wishing the narrative had been more straightforward.

Now that Clint was part of the Hollywood hierarchy I’m assuming he had the clout to experiment on occasion. However, I get the feeling with High Plains Drifter that Clint’s still trying to find himself as a director.

It does look good though, and the poster was quite impressive as well.

Unfortunately, I stupidly cut the corners off mine because I thought that made it look even better. A good copy is worth in excess of $400 these days. Oops.

The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

This film was originally supposed to be directed by Philip Kaufman, but Clint Eastwood took over the directing reins soon after production began.

Despite such an inauspicious start, it turned out for the best because Josey Wales is without doubt Eastwood’s best Western to date.

As Wales, Clint is the complete opposite of the character he played in the Dollar trilogy. He’s a farmer, he’s a family man, he loves, he loses, he cries, then before you know it he reverts to type by spitting chewing tobacco juice in all directions, killing, maiming generally causing all kinds of trouble and mayhem, so you get the best of both worlds.

With a great script by Kaufman and Sonia Chemus, based upon Forrest Carter’s novel, Gone to Texas, this has just about everything you need to create a perfect Clint Eastwood Western.

The supporting cast is superb, with actors Bill McKinney as Captain “Redlegs” Terrill, John Vernon, Sondra Locke, Woodrow Parfrey, and John Russell rounding out the complement of Eastwood stock company actors.

There’s also a wonderful performance from Chief Dan George as a randy Cherokee Indian, who nearly steals the whole show from right under everybody’s nose.

There’s a real warmth at the heart of this film that is frankly missing from Clint’s other cowboy movies.

Despite the narrative proving to be a combination of a revenge story, a Civil War epic, along with bounty hunters on the loose, Native Americans on the warpath and killer Comancheros all thrown into the mix, the whole thing is underpinned by the need for domesticity and the establishment of community.

Wales suffers the loss of his wife and son at the hands of the Union Redlegs then spends most of the film, almost as a younger version of Ethan Edwards, turning his back on hearth and home until he realises that the ragbag of individuals he has picked up along the way constitute a newfound family of its own.

Unlike Edwards, he finally embraces the community he himself has protected all along.

There are so many memorable moments in the film it’s hard to know which to choose, but my favourite sequences revolve around the comedic interplay between Eastwood and Dan George.

I like in particular the following exchange between the two of them after they’ve been involved in a gunfight with a bunch of redleg soldiers;

[Dan George] “I guess we ain’t gonna see that Navajo girl again.”

[Eastwood] “I guess not. I kind of liked her. Then it’s always like that.”

[Dan George] “Like what?”

[Eastwood] “After I get to likin’ someone they ain’t around long.”

[Dan George] “I notice that when you get to disliking someone they ain’t around for long either”

In fact, having watched it again, I’d say the script should have been nominated for an Oscar, just as the great score by Jerry “The Wild Bunch” Fielding was.

If I were pushed to produce a list of my favourite Westerns of all time – which I’ll probably do one day soon – this would definitely be near the top.

I mean, Clint even gets to ride off into the sunset at the end. How good is that?

Pale Rider (1985)

Pale Rider (1985)

After the wonderful Josey Wales, Eastwood tries another Twilight Zone Western in the style of High Plains Drifter.

There’s a slightly spooky air to the whole thing, what with Clint seemingly able to disappear into thin air whenever the mood takes him.

It’s almost a “Now you see him, now you don’t, now he’s back and oh, he’s just shot me” kind of thing.

To say the film is also highly reminiscent of Shane is putting it mildly.

For starters, there’s an Alan Ladd / Van Heflin tree-stump bonding exercise featuring Clint and co-star Michael Moriarty, only it’s a boulder instead of a tree.

One of the good guys gets the Elisha Cook Jr. treatment, only instead of being blasted by a single gunfighter, he’s summarily executed by seven gunslingers instead.

Moriarty plays a character called Barret, which is about as close to Van Heflin’s character in Shane, Starrett, as you can get.

On the other hand, there’s no young boy like Brandon DeWilde, just a very pretty young girl on the threshold of womanhood who requests that Clint teach her in the ways of love.

Luckily for Clint he declines, otherwise he’d be meat for the #MeToo movement.

Having said that, as Clint rides away at the end, the young girl runs after him just as the kid did in Shane, her voice echoing back from the mountains in the distance, just like the kid did in Shane, so I can’t help feeling that this film is a post-modern existentialist metaphysical reimagining of the Alan Ladd classic.

It’s quite an eclectic cast, with John “Nathan Burdette / Lawman” Russell as killer Marshal Stockburn, Richard Kiel and ex-Miss Neil Young, Carrie Snodgress.

Clint plays a character called the Preacher (as opposed to the Stranger), but a preacher capable of taking on four varmints on his first appearance by improbably defeating them with a couple of wooden bats, and then at a later point smacking Richard Kiel in the nuts with a sledgehammer.

It’s land-grab time again down in the valley, only it’s a fight over gold rather than just the land itself. The villain, Richard Dysart, gives Preacher boy twenty-four hours to leave with the miners, or “tin-pans” as they called, otherwise he’s going to ride them out of the canyon. The fool. Doesn’t he know anything?

You don’t give Clint an ultimatum and expect to make it to your next birthday.

The Preacher negotiates a deal with Dysart in which the tin-pans are paid a thousand dollars each to abandon their mining rights. They decide to stay, a decision that Clint relays to the bad guys.

Then he rides off, just like he did in High Plains Drifter. This time though he’s gone to fetch his guns, leaving behind his preacher collar in the process. He’s used the situation between Dysart and the tin-pans to lure Marshall John Russell out into the open, on account of he and Clint have a reckonin’. “It’s an old score and it’s time to settle it”, declares Clint, so I don’t think there’s any ambiguity here like there was in High Plains Drifter.

Okay, you might want to figure out how come Clint has six bullet wounds in the back yet he’s still standing upright, but I’m guessing that’s just down to pure luck.

I liked composer Lennie Niehaus’ musical reference to The Wild Bunch, the appearance of Marshall Stockburn and his gang of six always accompanied by a drum beat similar to the sequence in which the doomed Bunch members march into the village to rescue their friend, Angel. The soundtrack tells us that these gentlemen are going to die and they’re going to die bloody, just like Pike Bishop and his gang.

The final showdown is worth the wait, Clint gunning down the four men he met at the beginning before taking out Russell’s men one at a time.

Russell finally recognises whoever Clint is supposed to be, exclaiming ‘You!’ before Clint beats him to the draw and plugs him full of holes, finishing off with one between the eyes.

It’s a good film, and enjoyable in its way, but not as good as The Outlaw Josey Wales.

Unforgiven (1992)

If this is going to be Clint Eastwood’s acting and directorial swansong to the Western, then he’s going out with a real masterpiece.

It also garnered the man who used to be known as Rowdy Yates both Best Picture and Best Director Academy awards which meant that after nearly thirty-five years in the business the kid had finally made it.

The film visits a subject that lies at the very heart of the genre that, up until this point in time, apart from some of Peckinpah’s cowboy movies, had not really been highlighted within the narrative of a major Western before, namely violence and the effect it has on those who practise it for a living.

It goes without saying that Unforgiven is, therefore, a very dark and very violent film in its own right, probably the most violent since Eastwood and Leone’s Dollar Trilogy.

It’s interesting to compare this film with The Outlaw Josey Wales, which in effect Eastwood does himself, by highlighting the difference between the character of Wales and the character he plays in Unforgiven, ex-gunfighter turned dirt farmer William Munny.

At the beginning of the earlier film Josey Wales, who is also shown to be a farmer, retrieves his buried six-guns after his family has been slaughtered, then proceeds to test his rusty shooting abilities by accurately hitting a wooden post numerous times.

We see almost the exact same scene in Unforgiven, only this time Munny, who has decided to try and claim a reward on offer to kill two cowboys who have assaulted and mutilated a prostitute, can’t hit a tin can on a post just a few yards away.

He, therefore, resorts to blasting it from close quarters with a double-barrelled shotgun. Not only that, he can’t even ride his horse properly.

It’s an interesting counterpoint showing that during the intervening sixteen years between each film, Eastwood’s cowboy character has grown older and less capable than his younger self.

Conversely, Eastwood the actor has grown in stature to the point that he also receives his first nomination for Best Actor.

As he did with Josey Wales, Eastwood surrounds himself with excellent character actors to play against, most notably Gene Hackman as the no-nonsense sheriff “Little Bill” Daggett, Richard Harris as notorious gunfighter English Bob, who eventually turns out to be not only genuinely English but a Cockney as well, and Morgan Freeman as doomed ex-gunfighter Ned Logan.

Munny, Logan and a young pretender by the name of the Schofield Kid, team up and ride off to the town of Big Whiskey in order to kill the two wanted men in question and get themselves some much-needed cash.

Unfortunately, Little Bill is waiting to discourage anyone prepared to come to his town in order to kill anyone, and despatches English Bob then Munny in similar fashion by kicking the crap out of the both of them.

Bob wisely takes the next boat back to Blighty, but Munny is made of sterner stuff.

What with this being a Clint Eastwood Western, things eventually come to a head, sparked by Daggett’s murder of Ned and the Sheriff’s insistence on displaying Ned’s corpse in the window of the local saloon come brothel.

Munny exacts revenge by shooting the unarmed proprietor of the establishment after which he states to an outraged Little Bill that “he should have armed himself if he’s going to decorate his saloon with my friend”.

Munny then proceeds to slaughter anything that crawls or moves in the saloon, wounding the sheriff in the process. He reloads his shotgun, points it at Little Bill’s head then, after a brief exchange about seeing each other in hell, Munny pulls the trigger and shoots Daggett in the face.

To this day I still clearly remember watching that scene the first time and being completely caught out when Munny kills Daggett.

I honestly didn’t believe he was going to murder someone in cold blood but then, of course, that’s exactly what he would do. Munny, Daggett, English Bob, Ned – they’re all killers, and Munny, haunted by nightmares of the people he’s murdered over the years, is the worst of the lot.

This is a superb movie and one that warrants watching a number of times, as I have myself done over the years.

It’s got a great script by David Webb Peoples, a beautiful theme tune composed by Eastwood himself, wonderful location shooting in Alberta, Canada, and a memorable Best Supporting Actor performance from Hackman as Little Bill.

If you’re interested, there was a remake of the film released back in 2013, set in 19th-century Japan.

So, now that you’ve read the reviews on Clint’s cowboy oeuvre, here’s the ranking of my top ten Clint Eastwood Westerns starting with not so good to brilliant:

- Hang ‘Em High

- Two Mules for Sister Sara

- Pale Rider

- Joe Kidd

- High Plains Drifter

- For a Few Dollars More

- A Fistful of Dollars

- Unforgiven

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly