I first started writing about maverick director Sam Peckinpah way back a couple of years ago when I put together a birthday celebration Facebook post on his work, most of which I am reproducing here for the first of this five part article.

It’s difficult to write something new on Peckinpah that hasn’t been said already so I thought I’d just concentrate purely on his Western films as well as the two main TV shows he was involved in, “The Rifleman” and “The Westerner”.

This article includes one or more affiliate links. If you choose to purchase any of the items we have mentioned in this article, we may receive a small commission.

The TV Years

I’m also going to include other TV work, specifically an episode he directed for “The Dick Powell Show” in 1962 entitled “The Losers” in which Peckinpah attempted to update the characters from “The Westerner” in a modern-day setting. I’ll also take an in-depth look at his highly acclaimed adaptation of the short novel “Noon Wine” which Peckinpah directed for TV in 1966.

Okay. Let’s go!

Sam Peckinpah

A few hundred words to celebrate the director Sam Peckinpah is never going to be enough to do justice to one of the most innovative and controversial directors ever to have worked in Hollywood, but I’ll give it a try.

Starting out as a production assistant in the early 1950s Peckinpah tried his hand at acting with uncredited roles in “Wichita” and “Invasion of the Body Snatchers”. Turning to writing he cut his teeth on shows such as “Gunsmoke” and “Have Gun Will Travel” before helping to co-create “The Rifleman” in 1958, a series in which he both directed and wrote a number of episodes.

After that Peckinpah worked on a show which he created from scratch, the cult series “The Westerner” in 1959. In 1961 he then embarked upon a big-screen directing career that spanned barely twenty years, Peckinpah going on to deliver fourteen full-length feature films, six of them Westerns.

After having had his script for “One-Eyed Jacks” rejected by Marlon Brando, who also fired director Stanley Kubrick and then directed it himself, Peckinpah made his not-so-well-received motion picture directorial debut in 1961 with the Western “The Deadly Companions” starring Brian Keith and Maureen O’Hara.

The following year, however, Peckinpah hit paydirt in 1962 with “Ride the High Country”, a stone-cold classic with superb performances from two of the brightest cowboy stars to ever grace the silver screen, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott.

Like most of his Westerns “Ride the High Country” is as much an elegy to the passing of the West as it is a rumination on self-respect and honour for protagonists who exist mainly outside of the law.

A difficult man to work with at the best of times Peckinpah alienated so many people in Hollywood it would be another three years before he got to direct his next film, “Major Dundee”, released in 1965.

At around the same time his script for the cavalry movie “The Glory Guys” made it to the screen but directing duties went to Arnold Laven, who turned what Peckinpah considered to be a good script into ‘a wretched film’.

In the same year, he was hired to direct “The Cincinnati Kid” but was then replaced by Norman Jewison four weeks into production.

Things didn’t fare that well during production of “Major Dundee” which starred Charlton Heston in the main role. The film flopped at the box office, consigning Peckinpah to the wilderness once more before he bounced back into favour with the film he is most famous for, “The Wild Bunch”, released in 1969.

The success of “The Wild Bunch” finally gave Peckinpah a free hand to make the films he wanted to make, for a while anyway. “Straw Dogs”, a thriller set in England and starring Dustin Hoffman and Susan George brought in the crowds as well as criticism for its violent and explicit sex scenes, whilst “The Getaway”, a modern-day gangster thriller starring Steve McQueen and “Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia” proved that Peckinpah could work just as successfully outside the Western genre if he chose.

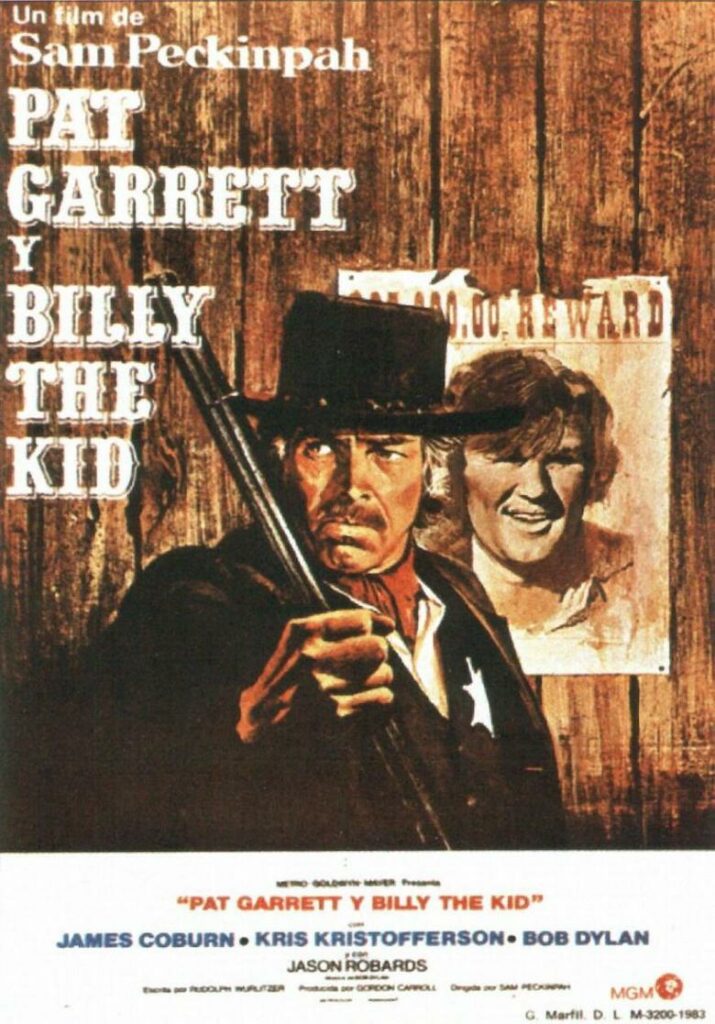

Peckinpah’s final Western, “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” is, in retrospect at least, hailed as one of the director’s best even though he found himself back in contention with studio heads during and after production of the film.

Starring James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson, with an interesting acting turn by Bob Dylan who also supplied the soundtrack, the movie can now be found on DVD in three different versions, all of which illustrate in one way or another Peckinpah’s mastery of the genre.

After producing another highly acclaimed film, the WWII German saga “Cross of Iron”, the director’s next movie “Convoy”, a comedy based upon a popular CB song of the time by singer C. W. McCall rather surprisingly turned out to be his biggest box-office success to date.

Unfortunately, it was too little and too late. Peckinpah’s demons got the better of him and after directing the poorly-received thriller “The Osterman Weekend”, his cinema career was over.

His legacy, however, lives on in so many films it would take a lifetime to list them here. Suffice it to say Peckinpah’s influence as a ground-breaking director still reverberates to this day so “Bloody Sam” must have been doing something right.

The Rifleman

Sam Peckinpah mainly eked out a living in the mid to late 1950s as a writer for Western TV shows such as “Have Gun Will Travel” and “Gunsmoke.

It wasn’t until he was approached by producer Jules Levy in 1958 that he finally managed to get involved in a series of his own, Levy hiring him to write the pilot for a show that would eventually evolve into the hit series “The Rifleman”.

Airing as an episode of the anthology series “Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theatre” in March 1958 the pilot, entitled “The Sharpshooter”, featured Chuck Connors as Lucas McCain and Johnny Crawford as his son Mark.

Despite his close involvement when it came to developing the series Peckinpah only actually wrote six episodes, four of which he also directed. The basis for the pilot came from a rejected script that Peckinpah had written for “Gunsmoke” so it could be argued the concept for the series was as much down to him as anyone else.

“The Rifleman” debuted on TV in September 1958 starting with the original pilot that had aired earlier that year.

Peckinpah directed the fourth episode in the first season, “The Marshall”, in which Marshall Fred Tomlinson, played by R.G. Armstrong, is killed and then replaced for the rest of the series by Paul Fix as Marshal Micah Torrance.

The show followed the exploits of McCain, an ex-Union Army Civil War veteran and a single parent, as he raises his young son in the town of North Fork.

Being an expert with a rifle he is naturally called upon to demonstrate that expertise on a regular basis to the numerous outlaws and villains that make the mistake of causing trouble in and around town that particular week.

The series proved to be highly popular, running for a total of 168 half hour episodes from 1959 to April of 1963. Apart from Connors, Crawford and Paul Fix the show featured other recurring characters such as bartender Frank Sweeney (Bill Quinn), blacksmith Nels Swenson (Joe Higgins) and hotel owner Mallory House (Patricia Blair).

Other directors of note who worked on “The Rifleman” included Arthur Hiller, Ted Post, actress/director Ida Lupino and Budd Boetticher. A number of well-known names contributed to the occasional script including Tom Gries, actor Robert Culp, Bruce Geller and Harry Julian Fink.

As already mentioned Peckinpah wrote a number of episodes as well but by the end of 1960 he was no longer associated with the show, putting his efforts at that point into a new TV Western project, “The Westerner”, details to follow shortly.

Famous and soon-to-be-famous guest stars that appeared throughout the run of the show included Sammy David Jr., James Coburn, Robert Vaughn, Adam West, Harry Carey Jr., Warren Oates and Dennis Hopper.

Chuck Connors reprised what is probably his best-known role as rifleman Lucas McCain in the TV movie “The Gambler Returns: The Luck of the Draw” in 1991, featuring alongside TV cowboy contemporaries Hugh “Wyatt Earp”, Clint “Cheyenne” Walker as well as Johnny Crawford who of course had played his son in “The Rifleman”.

The Westerner

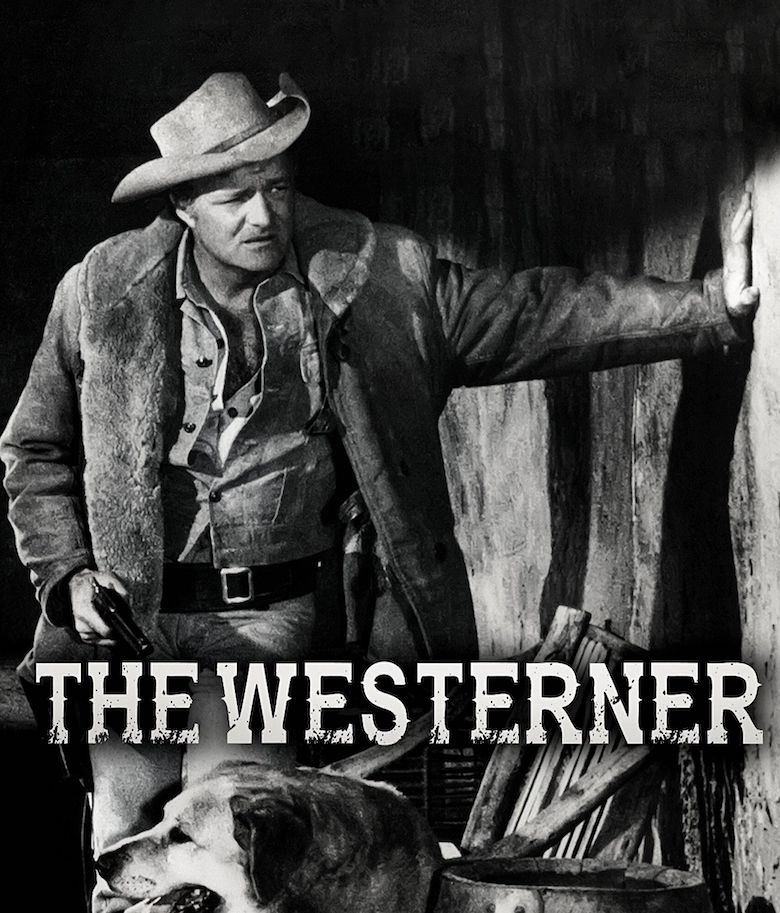

Considering that “The Westerner”, which debuted on NBC in September 1960, was created by Sam Peckinpah, it’s a real shame that it only lasted for one season.

According to biographer David Weddle, author of “Sam Peckinpah: ‘If They Move… Kill ‘Em!”, the main character Dave Blassingame, played by Brian Keith, would be “A simple saddle tramp… wandering from one job to the next, talking about settling down someday, but never saving enough money to make it happen”.

The director aimed for as much authenticity as he could, bearing in mind the restrictions of the prevailing censorship of the times. According to Weddle “he insisted that the actors’ clothing be convincingly aged and grungy” and that “the saloons would be…so real the people at home could smell the stale beer on the floorboards, the sour stench of tobacco juice in the spittoons”.

Blassingame was accompanied by his faithful dog Brown, played by Spike who also appeared in the title role of “Old Yeller”. Peckinpah had created and written an unofficial pilot for “The Westerner” the year before which featured as an episode for the ‘Dick Powell Zane Grey Theatre” anthology show entitled “Trouble at Tres Cruces”.

“The Westerner” ran for thirteen episodes, Peckinpah directing five with a co-writer credit on four of them. Apart from the dog, the only other recurring role of any note was played by John Dehner as Burgundy Smith, a no-good con man who crosses paths with Blassingame in a number of episodes.

Keen-eyed observers will catch sight of a number of performers who would feature eventually in Peckinpah’s later big-screen outings including Warren Oates, Slim Pickens, Dub Taylor, R.G. Armstrong and Katy Jurado.

Despite the combination of the calibre of the aforementioned above guest stars as well as the involvement of Peckinpah himself the show never really found an audience, NBC pulling the plug after just the one series.

Weddle quotes Brian Keith as maintaining that “CBS came running with an offer to put ‘The Westerner’ back on… [They wanted] to cut the realism and make it for kids – in other words, cut everything out of it that made it good”. As Peckinpah put it himself, “It was a successful failure. Win, lose or draw, I am proud of my work.”

Intriguingly the show can lay claim to having inspired the Charlton Heston oater “Will Penny”, released in 1967. Episode eleven of “The Westerner”, entitled “Going Home” and featuring Robert Culp, provided the basis for the later film, with director Tom Gries writing and directing both the episode and scripting “Will Penny”. For the sake of completion, Slim Pickens also featured in the TV episode as well as the movie.

The story didn’t end there though. Apart from the aforementioned “The Dick Powell Show” episode “The Losers”, which I’ll get to in part 2, Brian Keith went on to reprise his role from “The Westerner” over thirty years later in the TV movie “The Gambler Returns”, starring alongside other TV cowboys including Gene “Bat Masterson” Barry, Jack “Bart Maverick” Kelly and Chuck “Lucas McCain” Connors.

The Westerns of Sam Peckinpah Part II

(The TV Years)

The Losers

First aired in 1963 as an episode of “The Dick Powell Theatre” anthology series, “The Losers” was Sam Peckinpah’s attempt to try and update the two main characters of his earlier TV series “The Westerner” into a modern day setting presumably with the intention of creating a spin-off series as well.

Lee Marvin took on the part of Dave Blassingame, the role originally created by Brian Keith whilst Keenan Wynn starred as Burgundy Smith, previously portrayed by John Dehner.

Co-written with Bruce “Mission Impossible” Geller, guest host Robert Mitchum informs the audience at the beginning that “The Losers” is a story which takes ‘a closer look at the modern yet untamed West’.

The story concerns the adventures of Dave Blassingame, a man on the make in the town of Hondo, Texas, first seen selling a lame horse at an overblown price to a mark at a horse dealing convention in the town hotel.

Seemingly at a loose end he gains entrance to a high-stakes poker game only to confront card-sharp Burgundy Smith who is into Blassingame for nearly $200 dollars. As a favour Smith introduces the other players, amongst them an evil looking SOB by the name of Mr Anston (Mike Mazurki).

It soon become apparent that Dave and Smith, who for some reason is the only one in the room wearing sunglasses, are occasional partners in crime, Dave realising he is required to distract the other players by knocking over a drink whilst his erstwhile friend switches cards.

Smith takes Anston for all his money, leaving him and Dave to celebrate their winnings with the two hotel waitresses who have been serving drinks during the game.

This being the early 1960s there was obviously an obligatory requirement to introduce a dancing sequence in every Hollywood movie and TV series going but even so, the sight of Lee Marvin performing the twist is a weird thing to witness and subsequently very hard to erase from one’s memory bank.

Putting on Dave’s sunglasses whilst still doing the Twist Dave realises the glasses enable the wearer to read hidden markings on the back of each card, at the same time also discovering that Anston took one of the cards with him after losing the game.

One of the waitresses tells them Anston always does this whenever he loses to check that no one has ‘snuck in a pack of readers’. She also informs both men that she and her friend have bene paid to keep them entertained whilst Anston checks the cards.

Anston and his men return to confront the two men after which a chase ensues in the hotel lobby, reminiscent of a similar scene in the comedy classic “Some Like It Hot”.

In the confusion Dave and Smith drive off accompanied by Dave’s dog Brown, with Anston and his men in pursuit, the occasional speeding up of the film and the old-time piano music on the soundtrack emphasising the ‘silent-movie’ nature of the sequence.

What with there being a large dollop of comedy in the heart of the narrative, something that tended to be missing from the “The Westerner” series, it should come as no surprise that the minute the two men evade their pursuers Dave forgets to put on the brakes of his van which then rolls down a hill and smashes into a vehicle selling milk and eggs.

Running off into the countryside after realising Anston is still after them Dave and Smith hide in the back of a vehicle owned by blind musician Johnny (Adam La Zarre) and his young companion Tim (Michael Davis).

Johnny offers a ride to the two strangers, informing them he and Tim are bound for a town called Madeira to play at a gospel meeting. As Johnny sings a song before retiring for the night Dave and Smith ruminate on whether it’s worth hi-jacking the blind man’s vehicle but decide in the end it wouldn’t fetch that much money.

The following morning the four of them, with Smith at the wheel, chance upon a small homestead and decide to see if they can rustle up some food. The cantankerous farm owner agrees to feed them in payment for doing a few chores on the homestead in return.

Melissa (Rosemary Clooney), daughter of the farmer, suddenly appears on the scene, the father trying to deflect any interest from the strangers in her by declaring “ugly, ain’t she?”

Dave and Smith take on a week’s work in exchange for a couple of pairs of barely useful boots as well as offering to help refurbish a rundown truck in the barn. They then sit down to a meal cooked by a mostly silent Melissa.

Johnny plays her a gospel song called “He Told Me So”, everyone joining in apart from the daughter until the end when she surprises everyone by revealing a pleasant singing voice.

As she continues to sing the father interrupts, demanding she stop making a fool of herself. Dave suddenly hears his dog Brown barking for help so he, Smith and the farmer run off to check out what’s going on whilst Johnny and Tim stay with Melissa, Johnny demonstrating his lack of repertoire by serenading the two of them with the same song he’d sung the night before.

Meanwhile it turns out Brown has been chasing a racoon, a sequences which ends in Dave trying to shake it loose from a tree, falling out of the tree and then being accidentally whacked over the head by Smith who somehow has mistaken Dave for the racoon.

The following day Johnny and Tim resume their journey to Madeira, are off to Madeira, Johnny inviting Melissa to join them if she can. Seeing that Melissa is down in her cups Dave and Smith offer to escort her anywhere she would like to go, Melissa asking if they could take her to see Johnny and Tim in Madeira.

Upon finding Melissa all dressed up to attend the gospel meeting her father lights into her, exclaiming “You’re my shame and I’m keeping you where you won’t be seen. Your mother was beautiful and then she had you.

You were the start of her dying and for what? Look at yourself”, although none of this really explains the issue between the two of them. She still goes to the ball though, Dave and Smith persuading her father to let his daughter go by the simple act of waterboarding him until he says ‘yes’.

Dave and Smith take Melissa to the gospel meeting in the farmers now refurbished truck, she then joining in with Johnny and Tim as they sing “He Told Me So” to the congregation in Madeira. Happy that the farmer’s daughter is now in good company Dave and Smith leave the meeting, Dave dropping his last dollar in the collection basket.

When he gets outside he’s just in time to witness Smith driving off without him. Smith then suddenly reappears with Anson and his boys still on their tail. Dave jumps on the running board as they speed off into the night.

An interesting addition in terms of Peckinpah’s output with a couple of slow-motion sequences and a card game shot in a series of static images to demonstrate a couple of the director visual calling cards, but not really enough of a story at the cenre of the piece to engage a contemporary audience.

No one else associated with the Sam Peckinpah stock company of actors appears in the episode apart from Dub Taylor in a small role as a hotel greeter. It does however raise the question as to why the director and Lee Marvin never got around to working together on the big screen.

The actor would have definitely given William Holden a run for his money in the role of Pike Bishop, that’s for sure.

On the whole “The Losers” is awash with too much broad humour and incessant whistling on the soundtrack that constantly signals to the audience the whimsical nature of what is unfolding before them.

This lack of subtlety serves only to diminish the plight of Melissa, trapped into a life of drudgery at the hands of her unpleasant father. File under ‘mildly entertaining’ and then move on.

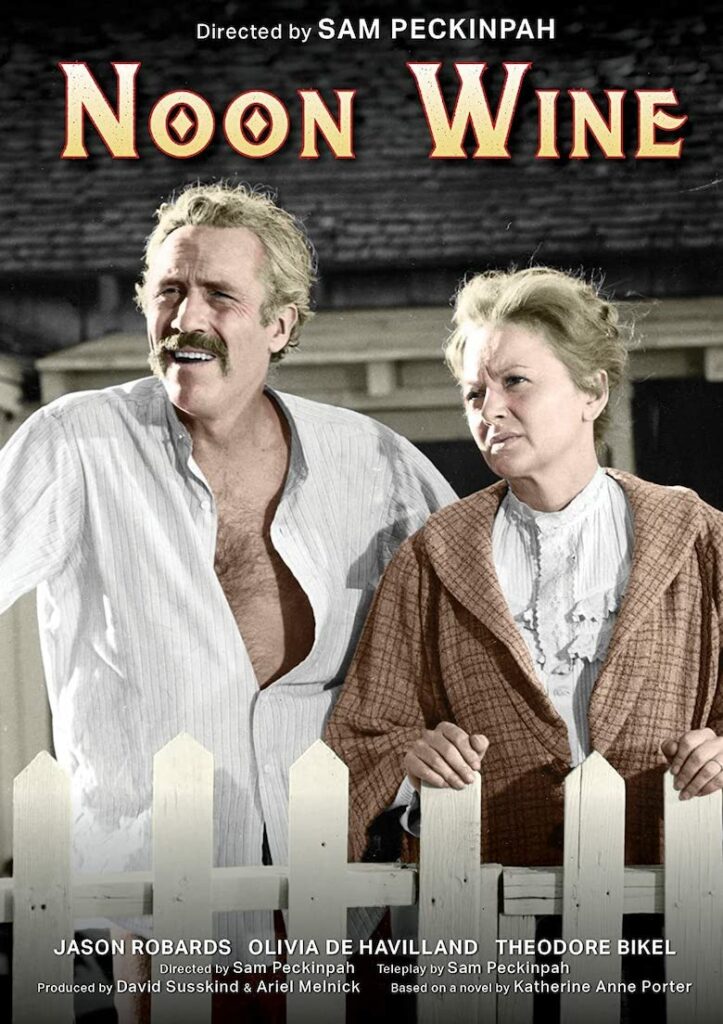

Noon Wine

The mid-1960s was not a good time for Sam Peckinpah. The failure of “Major Dundee” at the box-office, the seemingly interminable issues with Hollywood producers and his firing as director from “The Cincinnati Kid” four weeks into production naturally took its toll on him.

Salvation came in the guise of the TV movie “High Noon”, a highly acclaimed one-hour teleplay broadcast on American TV in 1967, starring Jason Robards and veteran Hollywood actress Olivia de Havilland and based on a short story by Katherine Ann Porter.

Set in the late 19th century on a small Texas farm, the opening shot of young children playing together is by now almost a Peckinpah visual motif, one that occurs numerous times in both his TV and film work.

The farm, run by Royal Thompson (Jason Robards) receives a visitor, Olaf Helton (Per Oscarsson ) who is looking for work. Thompson strikes a deal to pay Helson seven dollars a month seeing as the dairy farm isn’t doing too well and Thompson’s wife Ellie (Olivia de Havilland) is frequently indisposed due to illness.

Helton proves his worth, particularly to Ellie, when his efforts start to make the dairy farm more of a going concern. After a somewhat monosyllabic Helton abruptly leaves the table after supper Ellie chastises her husband for not being as productive on the farm as their new worker, Royal having earlier gone to town and arrived back after a few swigs of drink too many.

Royal confesses his feelings to Helton that he thinks running a dairy farm and chasing chickens is more of a “woman’s work” than anything else and “slopping hogs” is not for him.

As for cow’s Royal maintains “I don’t change the diapers on my kids so why should I wean a calf?” He is happy with Helston’s work and gives him a raise to ten dollars a month but the mood soon changes when Royal and Ellie’s two boys, Arthur (Steve Sanders) and Herbert (Peter Robbins), discover Helton’s harmonicas and start playing them without his permission.

Helton overreacts to this more than one would normally expect someone to behave over something as innocuous as two children playing with his harmonica but once the dust clears all parties settle down and life goes on peacefully down on the farm.

Three years pass by in relative harmony until one day a man by the name of Homer T. Hatch (Theodore Bikel) arrives at the farm and informs Royal that he is looking for Olaf Helton.

It transpires that Hatch is a bounty hunter and that Helton was once incarcerated in a lunatic asylum, Hatch also commenting that Helton was forever playing the same song on his harmonica which both men can now hear in the distance.

Royal states that he “don’t see no reason holding against a man who went loony once or twice in his lifetime and I’d don’t intend to take no steps about it” until Hatch then tells him Helton ran his own brother through with a pitchfork.

Hatch is intent on arresting Helton but Royal is not having any of it, demanding Hatch leave his farm forthwith, arguing Helton “ain’t loony now. He’s like one of the family”.

As the argument intensifies Helton suddenly appears on the scene and confronts Hatch who is holding a knife. Royal is totally convinced that he witnesses Hatch stabbing Helton so picks up a nearby axe and kills Hatch with it.

Whilst Sheriff Barbee (Ben Johnson) goes looking for Helton a troubled Royal, now referred to as Mister Thompson by his wife, encourages Ellie to tell the sheriff that she saw Helton getting stabbed by Hatch and in defending his farm hand Royal had no choice but to hit the bounty killer with the axe.

She argues that’s not what she saw but that is what she will tell Barbee who accepts her version of the story but emphasises that there will still be a trial in which her husband is to be tried for murder.

The sheriff, accompanied by his deputy Justus McLollan (L.Q. Jones) and a small posse eventually find Helton hiding in a barn but are forced to restrain and kill him when Helton tries to seriously wound one of the sheriff’s men.

Barbee informs Royal and Ellie of Helton’s demise and that he found stab wounds on the dead man’s body. Ellis is appalled whilst a confused Royal declares “But I saw the knife.

I was there” to which a suspicious Barbee replies “I know you was there Thompson”, advising Royal to give some thought to getting himself a lawyer.

Royal’s lawyer advises him not to say anything and to let the jury decide for themselves if he is innocent or guilty. The jury find him innocent on all counts and Royal walks free but because he feels he didn’t really got a chance to tell his side of the story Royal decides to visit all of his neighbours along with his reluctant wife and impart the truth as he saw it.

After having explained what he considers the truth to be to deputy McLollan he and Eliie ride off to the sound of sarcastic laughter from McLollan, Ellie mournfully telling her husband that “life has become all one dread” and that she “doesn’t know how to go on living anymore”

Circumstances come to a head late one night when Royal’s sleepy ramblings of innocence and about how things might have been different if only Hatch hadn’t turned up to cause trouble pushes Ellie over the edge. Her screams awaken their two sons and the eldest, Albert, threatens to kill his own father if he upsets their mother again.

Realising no one is ever going to believe him when it comes to the death of the bounty hunter Royal tells the boys he is going to fetch the doctor for Ellie. Instead he walks to the barn and writes a note which concludes with the statement ”It was Homer T. Hatch who came to do harm to a harmless man. He caused all this trouble and deserved to die, but I’m sorry it was me that had to kill him”.

Royal then places a loaded gun under the chin and kills himself.

Jason Robards delivers a pitch perfect performance as the troubled farmer trapped in a loveless marriage. Although Olivia de Havilland as his wife is equally impressive it turns out Peckinpah wasn’t convinced she had captured a truthful reaction to the death of her husband in the final scene.

He berated and cajoled the actress on a personal level to the point where he finally caught what he was looking for, a look of quiet devastation that both encapsulated the effect on the wife of the suicide of Robards character as well as the unexpected attack from Peckinpah on de Havilland’s supposed failings as an actress.

According to Peckinpah biographers the critical success of the show, which garnered him nominations for Writers Guild Best Television Adaptation and Directors Guild Best Television Director, initiated a resurgence in his career that would eventually lead to an opportunity to get back in the saddle and deliver his masterpiece, “The Wild Bunch”.

“Noon Wine” is currently unavailable on DVD. However, a pristine copy was recently uploaded to YouTube, in colour as well, so check it out if you get the chance. Highly recommended.

The Westerns of Sam Peckinpah Part III

(The Movie Years)

The Deadly Companions

Released in June 1961, “The Deadly Companions” is the first full-length Western directed by Sam Peckinpah.

The opening sequence sets both the pace and the tone for the next ninety minutes or so, Brian Keith as an ex-Union army soldier called Yellowleg encounters Turk (Chill Wills), suspended from the ceiling of a saloon with a noose around his neck after having been caught cheating at cards.

Turk’s companion Billy (Steve Cochran) meanders in after having been entertained by a couple of ladies of the night just in time to watch as Yellowleg punches out the miscreants who had hung Turk up, the three of them leaving the saloon post haste.

Before exiting the bar Billy shoots out a mirror, pre-echoing a scene from the later “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” in which Garrett (James Coburn) does the exact same thing. Yellowleg assumes leadership of the group suggesting the three of them head over to Gila City which has a bank and a new sheriff, stating “it sure beats cheating at cards”.

Their arrival in town is greeted by a bunch of kids running around and taking verbal potshots at a young boy by the name of Mead standing atop a building and playing a harmonica.

The boys step in to tend the horses of the newly arrived trio just as Billy is in the process of warning Yellowleg about giving unwanted orders to him and Turk, whom Yellowleg has sent to the nearest blacksmith to get a hoof fixed on his horse.

Turk meets up with the other two at a saloon that doubles as a church with Parson (Strother Martin) leading the congregation in full swing. In the audience is saloon girl Kit Tilden (Maureen O’Hara) with her son, who happens to be the boy looking after Yellowleg and Billy’s steeds.

Yellowleg visits the town doctor to get a diagnosis on a bullet he’s been carrying around near his collar bone, the doctor recognising him as someone who had been scalped a few months before in another town whilst fighting with an ex-Confederate soldier. This explains why Yellowleg never removes his hat. He reveals to the doctor that he has come to Gila City to find the man who tried to kill him.

Still thinking that they have accompanied Yellowleg to the town to rob the bank, Billy and Turk approach it only to realise it’s already being robbed by a different gang. In the ensuing shootout, Yellowleg appears and accidentally kills the young boy Mead.

Filled with remorse he ends up accompanying Kit and her dead child to Siringo, which is smack in the middle of Apache territory. Realising the townsfolk holds her in disdain the mother wants Mead to be buried near where his father had died so Yellowleg cashiers Billy and Turk ride along with them as well. Billy is quite happy to be in the company of red-headed Kit but Turk has to be forced into it.

Kit is still angry about being accompanied by the man who accidentally shot her son but she changes her mind when the trio helps to fix Kit’s wagon after a wheel falls off in the middle of a river. During their first overnight camp, Billy’s liking for Kit gets the better of him and Yellowlegs is forced to throw Billy out to fend for himself, although he insists Turk stay with him and Kit.

However, in the morning Turk has ridden off, presumably going to Gila City with Billy to rob the bank. Yellowlegs rides after them but changes his mind, realising that he doesn’t feel good about leaving Kit in Apache country.

Continuing their journey to Siringo, Kit and Yellowlegs witness a bunch of drunk Apache warriors attacking a stagecoach. When it gets dark Yellowlegs steals into the Apache camp and steals a horse to replace one that Kit accidentally let run off earlier.

In order to cover their trail in case the Apache come looking for their stolen horse Yellowleg and Kit dismantle and bury their wagon and continue their journey on foot, the body of Mead being pulled along on a travois attached to one of the two horses they have left.

The ruse doesn’t work, however, and they soon find themselves under attack at night from the vengeful leader of the Apache party who is intent on scaring them first before killing Yellowleg.

The next day, down to one horse after the other steed breaks its leg, the couple still find themselves being trailed and taunted by the Apache. They camp once more only to discover the next day their last horse has now been killed.

They carry the coffin of the dead boy to a cave, Yellowleg telling Kit to stay there until he returns from a mission to kill the leader of the Apache tribe.

That night the Apache chief sneaks into the cave only to be shot to death by Kit with her trusty shotgun. She and Yellowleg finish their journey to Siringo where he helps her find the grave of her husband next to whom she wishes to bury her son.

Who should they bump into but Billy and Turk, both of them on the run from a posse after finally robbing the bank back in Gila City. Billy sends Turk off to fetch the money they stole, it finally transpiring that Turk was the man whom Yellowleg had been searching for over the previous five years.

Billy offers to hand Yellowleg back his gun in order to finish off Turk but it’s obvious to all concerned that Billy is still intent on having his way with Kit.

Despite their slowly simmering love for each other Yellowleg is still out for revenge, attempting to shoot Turk when he returns with the money but failing due to his aim being compromised with the bullet in his collar bone.

Billy helps speed things along by shooting Turk himself, but unfortunately for him, his aim isn’t any better, a wounded Turk shoots Billy in the back just as he’s about to face down Yellowleg.

Now given the opportunity to do to Turk what Turk had done to him five years earlier Yellowstone gives up the opportunity to scalp him at the behest of Kit.

The posse from Gila City arrives, Yellowleg insisting that the Parson say the right words over Mead once he’s been buried next to his father, a man the citizens of the town had not believed existed which led to accusations of Kit of being a fallen woman.

A demented Turk is led away by the posse, presumably to finally meet the fate that he had nearly suffered at the beginning of the film.

A Peckinpah cowboy movie that starts with a theme tune sung by Maureen O’Hara does not augur well for the audience and the end result supports that contention.

As you can probably tell from my synopsis, “The Deadly Companions”, to quote from another review of the film, is “kind of slow and gloomy in tone” and that the film is only notable because “it was directed by Peckinpah”.

There is a visual hint of things to come with Steve Cochran’s character Billy shooting point blank at a mirror, pre-echoing the scene in which James Coburn pulls the same stunt in “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” but other than that there’s not much to indicate Peckinpah’s later unique approach to the Western genre.

This is probably down to him being more of a hired hand than anything else and, true to form, falling out with his leading lady who incidentally had actually hired him in the first place, an unimpressed Maureen O’Hara declaring that Peckinpah “didn’t have a clue how to direct a movie”. Peckinpah himself wasn’t too enamoured with the end result either, stating that he would never again work on a movie in which he did not have script supervision and approval.

Brian Keith, who of course had previously worked with Peckinpah on the TV series “The Westerner” gives an excellent performance as the ex-Union army soldier who accidentally kills a young boy but, as Peckinpah himself indicated, he didn’t consider “The Deadly Companions” to be his first ‘real’ Western.

That would have to wait until his next film.

Ride the High Country

After the poor reception for “The Deadly Companions” everything appeared to come right for the director with his second full-length feature “Ride the High Country”, a stirring classic Western released in June 1962 featuring two of the most popular Hollywood cowboy actors of all time, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott.

Set in the early 1900s the opening sequence features a busy town hosting the arrival of a carnival, the gathering of the locals and a bunch of children running through the main street calling to mind the beginning of “The Wild Bunch”, albeit without the welter of blood and gore visited upon the innocent townsfolk in the later film.

Ex-lawman Steve Judd (Joel McCrea) arrives to take on a job involving the transportation of gold from the nearby mining town of Coarsegold. As he rides down the main street he mistakes the applause of the gathered crowds as being for him until he realises he’s wandered into the middle of a horse and camel race.

When he is then addressed as an ‘old-timer’ and nearly run over by an early automobile the message is clear: Steve Judd is a man out of kilter with the modern world. He then stumbles across an old acquaintance of his, Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott), plying his trade as a huckster in the guise of sharp-shooting legend the Oregon Kid.

Westrum and his sidekick Heck (Ron Starr) sign on to help Judd escort the gold from Coarsegold to the town bank, both of them intent on liberating the precious cargo at some point further along the trail, with or without Steve’s involvement.

On the way the three men chance upon a farm owned by Joshua Knudsen (R.G. Armstrong), a man of the bible who keeps his only daughter Elsa (Mariette Hartley) on a tight rein, a situation that arose after Knudsen’s now deceased wife had earlier abandoned him for another man.

When Hec is caught showing Elsa too much attention Joshua strikes out at Elsa and, against their better judgement, Steve and Gil allow her to ride with them to Coarsegold where she intends to marry her fiancé Billy (James Drury), one of the four notorious Hammond brothers to whom she is ‘kind of’ engaged to.

He makes his feelings known to Elsa but he goes too far, alienating her and driving her even further into the arms of Billy. Billy’s brothers Silvus (L.Q. Jones), Henry (Warren Oates) and Jimmy (John David Chandler) as well as their father, Elder Hammond) John Anderson) are also eager to make the acquaintance of the new addition to the family but for reasons too inappropriate to mention here.

Elsa finally starts to realise she’s made a mistake marrying into the Hammonds upon discovering that the marriage ceremony is to be held in a house of ill repute known as Kate’s Place.

She’s even more horrified when it turns out that Kate, the madam of the establishment, is to be the maid of honour and that the accompanying ladies of the night are her bridegrooms. To top it all the wedding is to be administered by the permanently drunk Judge Tolliver (Edgar Buchanan).

The ceremony degenerates into a free-for-all with Elsa narrowly escaping being degraded not just by her new husband but all of his brothers and their father too. Steve, Gil and Hec rescue Elsa with Gil purloining Tolliver’s licence to perform marriages in the state and ripping it up in an attempt to negate the validity of the ill-judged union between Elsa and Billy.

Having now gathered gold from the miners to take back to the bank in town the three men accompany Elsa as they leave Coarsegold. At this point Steve confronts his old friend Gil and Hec about their obvious intention to steal the gold, Steve explaining that he wants to “enter my house justified”.

He relieves them of their weapons but then has to rearm them when their party is ambushed by the Hammonds. Hec rises heroically to the occasion, killing both Jimmy and Silvus during the gunfight.

Intent on still taking the two men to jail Gil makes himself scarce but Hec stays a willing prisoner of Steve, belatedly admiring the older man’s intransigent sense of honour and prepared to try and rehabilitate himself with Elsa at the same time.

When they reach Elsa’s farm they find her father kneeling silently by the grave of his dead wife, unaware that he’s actually been killed by the remaining Hammonds who are hiding in the barn. Another shootout ensues with both Steve and Hec each catching a bullet in the exchange of gunfire.

Gil joins his beleaguered companions in a final showdown with Billy, Henry and their father, Steve ending up mortally wounded whilst the Hammonds are finally taken down. Gil promises a dying Steve that he’ll make things right regarding the delivery of the gold to the bank to which Steve replies “Hell, I knew that, I knew you would. You just forgot yourself, that’s all”.

As McCrea tells it in an interview he did a few years before he passed away, he was originally slated to play Scott’s role and vice versa. Peckinpah suggested they toss a coin for it and McCrea ended up taking on the man with a conscience whilst Scott got the bad guy role.

Also, it was Scott’s character who was supposed to die at the end but according to McCrea, it was Peckinpah’s idea to have Steve die instead, suggesting it would make a more powerful ending.

The script, initially written by N.B. Stone then polished by William S. Roberts and Peckinpah himself, is full of small moments that bring a wry smile to the face, especially one little sequence in which Steve is revealed to be an early climate activist, berating Hec for littering the landscape with the admonition “These mountains don’t need your trash”

Soon-to-be Peckinpah stock acting stalwarts such as Warren Oates, R.G. Armstrong and L.Q. Jones can be found in the cast along with a pre-Virginian James Drury and Mariette Hartley as the put-upon Elsa.

The film is beautifully shot in Cinemascope in the lush Californian landscape of Bronson Canyon and Inyo National Forest by cinematographer Lucien Ballard, who went on to work with the director again, most notably on “The Wild Bunch” and “The Getaway”.

As for “Ride the High Country”, there was now a new kid in town. His name was Sam Peckinpah and he had finally made his first real Western.

The Westerns of Sam Peckinpah Part IV

Major Dundee

One sometimes gets the feeling that it wouldn’t be a genuine Sam Peckinpah film unless there was drama behind the scenes including budget cuts, interfering producers and general mayhem on and off the set day and night.

“Major Dundee”, originally released in 1965, therefore fits the bill to a tee, reinforced by the appearance of a restored version of the film in 2005 upon which this article is based. The original story for the film was written by Harry Julian Fink who later went on to co-write the script for “Dirty Harry”, and whose screenplay for “Major Dundee” was rewritten extensively by Oscar Saul and Peckinpah himself.

Set in 1864 as the American Civil War starts to draw to a close, the movie is occasionally accompanied with a voice-over narration of events supplied by Trooper Ryan (Michael Anderson Jr.), the film starting with the aftermath of a massacre by Apache chief Charriba (Michael Pate) of a group of ranchers and a cavalry escort.

A number of children have been kidnapped by the Apache and Dundee (Charlton Heston), considered by his men to be officious and a martinet, is all for pursuing and rescuing them, sending out his one-armed scout Samuel Potts (James Coburn) to first locate Charriba and his warriors.

Dundee and his men return to the fort where the major has been put in charge of a group of imprisoned Confederate soldiers, a punishment for apparently disobeying his superiors at the battle of Gettysburg.

The prisoners, commanded by Captain Benjamin Tyreen (Richard Harris) also include five of his fellow soldiers, brothers O.W. (Warren Oates) and Arthur Hadley (L.Q. Jones), Sergeant Chillum (Ben Johnson) and Jimmy Lee Benteen (John David Chandler) who have attempted to escape.

In the process, they end up killing a Union guard so Dundee sentences Tyreen and his men to be hanged. The execution order is rescinded after Tyreen ‘volunteers’ himself and some of his men to help hunt Charriba down.

The Confederate captain’s hatred of Dundee stems from the major having voted for his former friend to be cashiered from the Union army for killing a fellow officer in a duel. Tyreen promises to obey Dundee but only until Charriba is either killed or captured. After that, all bets are off.

The search party eventually numbers individuals such as greenhorn Lt. Graham (Jim Hutton), horse thief Benjamin Priam (Dub Taylor), Reverend Dahlstrom (R.G. Armstrong) and mule packer Wiley (Slim Pickens).

Dundee also takes along a group of black soldiers led by Aesop (Brock Peters), which puts them on a collision path with some of the rebel soldiers who had fought for the right to keep slaves.

Potts returns with news that the kidnapped children are thinner but still alive, apparently enjoying their new lives under the Apache and even helping them make arrows. As the escort leaves the fort both Union and Confederate contingencies engage in the old Hollywood standby of attempting to drown each group out by lustily singing their preferred military anthems, in this case, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” versus “Dixie”.

Upon crossing the Rio Grande into Mexico Ryan notes in his diary that Dundee’s present war is now no longer with the South, it’s with the Apache.

At this juncture Tyreen keeps his word to stay faithful to Dundee, giving up the opportunity to escape when a Confederate patrol is glimpsed in the distance. T

he tension between the black soldiers and Jimmy Lee eventually explodes, forcing Dundee to intervene but not before the Reverend Dahlstrom visits the wrath of God upon Lee first.

A few weeks into the mission a wayward Apache walks into Dundee’s camp with the missing children, informing the major that Charriba is encamped not too far away.

Dundee takes some of his men to investigate and rides into a trap, ending up losing fourteen of his men, with another thirteen wounded and their supplies significantly reduced.

Dundee decides to try and get more supplies from a nearby village despite its closeness to a fort occupied by French fusiliers who are there in support of the Mexican army.

After liberating the village from the French, Dundee falls for the charms of Austrian widow Teresa (Senta Berger), vying with Tyreen for her attention.

Some of the French soldiers are intentionally allowed to escape to warn a nearby garrison of the American interlopers. When the French arrive to retake the village they are defeated and their supplies appropriated by Dundee’s men.

They take time out to recover from the tribulations suffered so far by retiring to an idyllic camp in a wood next to a shaded stream. The peace is quickly ruined when O.W. Hadley deserts.

He is brought back to the camp whereupon Dundee sentences him to death. Before the sentence can be carried out Tyreen intervenes and shoots his own man to defuse the situation but warning Dundee that when the mission is over he is going to kill him.

Teresa and Dundee taking a swim together in the stream but, before they can fully express their feelings for each other, Dundee takes an arrow in the leg from a group of Charriba’s men concealed nearby.

Despite his hatred for the major Tyreen saves Dundee’s life by despatching the Apache warriors. A wounded Dundee goes to ground in the nearest town to recover and whilst there falls for a young Mexican lady.

He and his new girlfriend are then discovered together by Teresa when she pays a surprise visit to see if he has recovered from his wound. One of the main restored sequences then follows in which Dundee, bereft at losing Teresa, slides into alcoholism, ending up drunk in the gutter with a dog for a companion.

With the help of Tyreen Dundee eventually sobers up, takes back command of his men and sets off once more to find Charriba. Making a run to the border they lure the Apache into their camp with beds made to look as though the soldiers are asleep.

In the ensuing battle, Charriba dies at the hands of bugler Ryan. Now that the Apache chief has been killed Tyreen and Dundee prepare to settle their differences only for a troop of French lancers to appear and spoil their face-off.

The Americans head for the border pursued by the lancers and then encounter more French soldiers waiting for them on the American side of the Rio Grande. A mid-river skirmish takes place during which Reverend Dahlstrom, Aesop and Arthur Hadley are killed.

Tyreen retrieves their lost flag and hands it over to Dundee. Fatally wounded, Tyreen charges recklessly into the midst of the lancers in order to distract the enemy whilst the rest of the soldiers make their escape, the Confederate captain going out in a blaze of glory.

As Dundee and the rest of his men make their way across the border a voiceover from bugler Ryan recites “April 19th, 1865, after a brief but costly battle with French irregulars we crossed the Rio Grande and re-entered the United States”.

Chuck, or ‘Chuck the Heston’ as he is referred to by L.Q. Jones in one of the special feature documentaries that accompany the restored version of the film, is described as magisterial and prone to posturing and posing whenever the camera is upon him.

However, it turns out Heston is also an unsung hero seeing as he requested the studio use his salary in order to complete the film.

The sudden ending reinforces the notion that despite this Peckinpah still had a number of scenes left to finish that either didn’t make it into the final cut or were never filmed in the first place.

The film is the closest that Peckinpah ever strayed into John Ford territory, especially as it deals with one of Ford’s favourite subjects, the nature of life in the military.

To reinforce the point Peckinpah also throws in a burial service complete with a rendition of “Shall We Gather at the River?” There’s also a little hint of what was to come in Peckinpah’s next film when, at one point in “Major Dundee”, the major and his men leave the village they had taken from the French, their departure accompanied by a group of singing Mexican villagers, a moment very reminiscent of the scene in “The Wild Bunch” when Pike Bishop and his men leave to meet up with Mapache.

Whether you watch the original release or the restored version of “Major Dundee”, the film is still not without its flaws and the failure at the box office left Peckinpah high and dry in Hollywood once more.

It would be another three years before he got the chance to direct a big-screen movie again and finally show he was a force to be reckoned with.

The Westerns of Sam Peckinpah Part V

The Wild Bunch

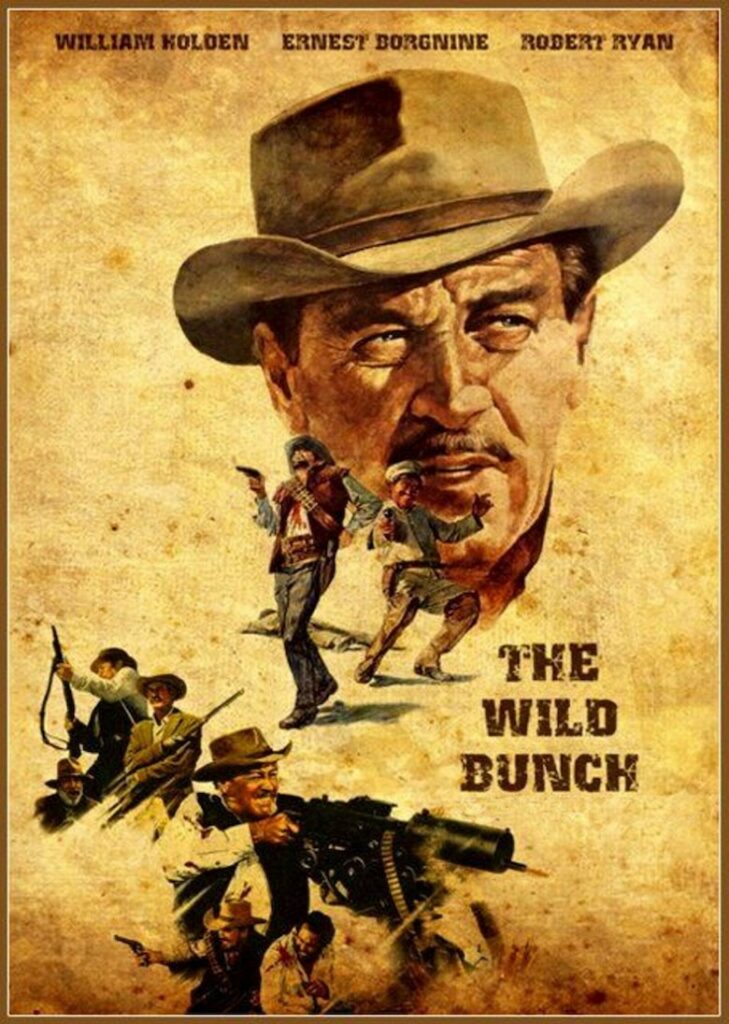

If Sam Peckinpah had only ever directed one film and that film was “The Wild Bunch” then he would still be assured a prominent place in the pantheon of the all-time greatest Hollywood directors that ever lived.

Audiences were unprepared for the scenes of explicit violence that exploded onto the screen when it was first released in 1969.

The movie is topped and tailed by two celebrated sequences of slow-motion bloodletting and orgiastic violence that have to be seen to be believed. It is without doubt the pinnacle of director Sam Peckinpah’s career, a masterpiece in every sense of the word.

It is one of the best Westerns to ever grace the silver screen and I can still recall watching the film for the first time, sitting in the cinema slack-jawed in total astonishment and amazement at the ground-breaking images that unfolded on the screen in front of me.

I’d never seen anything like it before, and I realised I’d probably never see anything like it again.

Any Western that followed in the footsteps of “The Wild Bunch” would forever be measured against a film that not only challenged the rules of what could and could not be shown on the screen but also finally set the seal on the ascent of Peckinpah himself, who went on to claim the title as the most notorious of all Hollywood maverick directors.

I’m going to keep the synopsis short as I’m sure anyone reading this will already be familiar with the film.

Disguised as American soldiers, Pike Bishop (William Holden) and his gang ride into the town of San Rafael intent on robbing the local bank, Bishop unaware that his former partner in crime, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), along with a motley crew of scavengers hired by the railroad, wait on the rooftops by the bank to pounce on the bunch.

The ambush turns into a massacre with Thornton’s men killing innocent townsfolk along with members of Bishop’s gang.

In the confusion, Pike rides away with six of his men, including Dutch (Ernest Borgnine), brothers Lyle and Tector Gorch (Warren Oates and Ben Johnson) and Angel (Jaime Sanchez). Pike is required to administer a mercy killing to one of his own who had been blasted in the face from a shotgun.

The remaining gang members rendezvous with old-timer Sykes (Edmond O’Brien) and start to parcel out the money from the bank job, only to find out the bags of coins have been substituted with metal washers.

The gang seeks food and shelter in Angel’s village whereupon Angel is told his girlfriend Teresa (Sonia Amelio) has left him for the vicious General Mapache (Emilio Fernandez) who is engaged in a campaign against the army of Pancho Villa.

The gang offers to work for Mapache who hires them to steal a trainload of weapons from an American army train just across the border.

Having killed Teresa after finding her in the arms of the general Angel requests that he is paid with one of the cases of weapons which he intends to use against Mapache at a later date.

The gang steals the armaments from the train and, with Deke Thornton still chasing after them, Pike and his men blow up a bridge in order to halt their pursuers before they can follow the bunch into Mexico.

When Bishop and his men deliver the weapons to Mapache the general kidnaps Angel, having been informed by Teresa’s mother that Angel had kept a case of the guns for himself.

Pike wrestles with his conscience as to the fate of Angel and, along with Dutch, Lyle and Tector, eventually face off against Mapache and his soldiers. In a tense standoff Mapache murders Angel, only to be gunned down himself by Pike and the gang.

A murderous shootout then takes place with the bunch killing as many of Mapache’s men as they can before they themselves die in a hail of bullets.

Old man Sykes, having dispatched the remaining members of Thornton’s gang with the help of Angel’s co-villagers, invites Thornton to join him in their fight for Pancho Villa and his army.

Apart from the opening and closing sequences, there are also two other brilliantly choreographed set pieces within the main body of the film, the first centred on the aforementioned train heist.

The other most memorable scene takes place prior to the climactic bloody shoot-out when the four remaining gang members, Pike, Dutch, Lyle and Tector decide to try and rescue Angel.

The four of them march in unison to a certain death, accompanied by the clashing cymbals and drum beat of Jerry Fielding’s superb soundtrack.

Some sources suggest that the role of gang leader Pike Bishop was originally slated for Lee Marvin, who apparently passed due to the similarity between “The Wild Bunch” and “The Professionals”, another Mexican border Western he had appeared in a couple of years before.

There’s even a suggestion that Peckinpah had also considered Richard Harris and Burt Lancaster but in the end, William Holden gives a career-best performance as the leader of the Bunch, brilliantly portraying a man out of kilter with an ever-progressive world and coming to terms with the fact that the only choice he eventually has left is to decide when and where he is going to die.

Ernest Borgnine, along with Ben Johnson and Warren Oates give their all alongside veteran Hollywood actors including Edmond O’Brien and the underrated Robert Ryan, with Strother Martin and L.Q. Jones bolstering the cast.

Whilst a number of contemporary reviews baulked at the explicit violence in the film, with one critic asking openly “why was this film ever made?”, other reviews were more measured.

Veteran critic Vincent Canby praised “The Wild Bunch” as ‘very beautiful and the first truly interesting American-made Western in years” whilst Roger Ebert opined it was “an important act of filmmaking”. As for Peckinpah himself he is quoted as saying that “I wasn’t trying to make an epic.

I was trying to tell a simple story about bad men in changing times. ‘The Wild Bunch’ is simply about what happens when killers go to Mexico. The strange thing is that you feel a great sense of loss when these killers reach the end of the line.”

In the final analysis, you either hate “The Wild Bunch” or you love it. For those of you who love it – we ride at dawn!

PS If you’re interested in the lowdown on the making of the film then I heartily recommend the following book by author W.K Stratton:

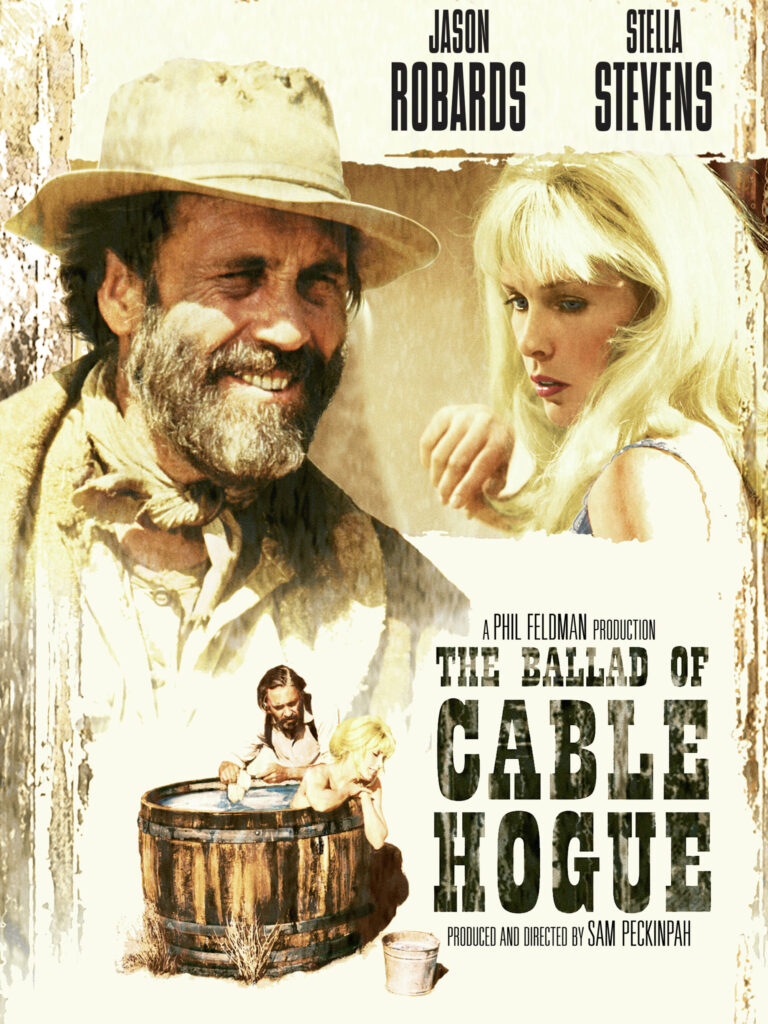

The Ballad of Cable Hogue

After the success of “The Wild Bunch” it wouldn’t have been unreasonable to expect something equally as brutal and controversial but instead, Sam Peckinpah wrong-footed both the critics and cinema audiences by following up his most famous film with the comedy Western “The Ballad of Cable Hogue”, released March 18th, 1970.

Set in the early part of the 20th century the film starts with prospector Cable Hogue (Jason Robards) left stranded in the desert after his two so-called companions, Bowen (Strother Martin) and Taggart (L. Q. Jones) ride off with all the water.

Hogue staggers around for four days and nights, conversing with God and promising that he won’t sin anymore if only the Almighty serves him up just a drop or two of cool water. His prayers are finally answered when he stumbles across a source of untapped water very near to a trail running through the desert.

Ben Fairchild (Slim Pickens), the driver of a passing stagecoach, informs Hogue that he’s dead centre between the towns of Dead Dog and Gila City and that anyone setting up a way station for people travelling from one town to another could make a fortune.

The good Lord provides Cable with even more bounty when the stagecoach speeds off and dumps the luggage belonging to two complaining travellers at his feet.

Business doesn’t get off to a very good start what with his first customer refusing to pay for water and then trying to kill him. Hogue gets off the first shot instead, delivering the opinion that the man was ‘seventeen kinds of a damned fool’. In a trigger-happy mood he then nearly blows off the head of the Reverend Joshua Duncan Stone (David Warner) who appears unexpectedly as if from nowhere whilst Hogue is burying his ex-customer.

After being forced to pay Hogue ten cents for water or feel the wrath of a loaded shotgun the Reverend, who turns out to be a self-proclaimed man of God, shows him a photo of one of his flock to which Hogue comments “she’s as naked a jaybirds ass”.

An attempt to blackmail Hogue by suggesting a lot of unsavoury types might be glad of knowing that he has yet to stake a claim on the land where he discovered the water backfires when Hogue takes off to Dead Dog in order to file his claim.

Upon arriving in town he (and Peckinpah’s camera) immediately falls for the charms of Hildy (Stella Stevens) although Hogue becomes perfectly aware very early on that Hildy loans out her charms to anyone willing to pay the going rate.

After buying a claim for two acres he goes to the stagecoach office and tries to make a deal with the boss, Mr. Quittner (R. G. Armstrong), to invest in his proposed way station but Quittner throws him out into the street where Hogue finds himself confronted by that most familiar of Peckinpah motifs, a group of playful children.

He then tries his luck at the nearest bank and, courtesy of bank manager Mr. Cushing (Peter Whitney), walks out with a loan of one hundred dollars and wisely decides to use some of the money to purchase some time with Hildy. She in turn wisely washes him first, telling him he smelt “bad enough to gag a dog on a gut wagon”.

Their relationship remains unconsummated due to Hogue being put off by the witterings of a local preacher outside in the street. Hogue is suddenly wary that the Reverend Stone has maybe sold him out and caused him to lose his land claim.

Finding Stone still present back at the way station Hogue shares a bottle of whiskey with the Reverend and then returns to town in order to finalise his unfinished business with Hildy.

Meanwhile, the Reverend shows his true colours by attempting to seduce a grief-stricken woman by the name of Claudia (Susan O’Connell), but before he can have his wicked way with her Claudia’s husband interrupts the proceedings.

Quittner finally realises it is best to go into business with Hogue and offers him a contract to feed and water his stagecoach passengers, Ben Fairchild signing off on the deal with the gift of an American flag which Hogue proudly displays on his land, now known as Cable Springs.

Reverend Stone decides to travel back to Dead Dog and finish the Lord’s work by finally making Claudia see the light whilst Hildy turns up unexpectedly to join Cable at the way station, having been ejected from the town by the good ladies of Dead Dog.

Domestic harmony is the order of the day for a while, with lots of lovey-dovey geese-chasing ‘Butterfly Mornings” and rump naked bathing out in the open until their garden of Eden is spoilt when the stagecoach arrives early and Hildy jumps butt-naked out of her bath to avoid the prying eyes of the passengers.

Hildy informs Hogue she’s going to be leaving soon to make a new start in San Francisco but it appears he doesn’t want her to go until he’s had his revenge with his traitorous ex-partners Taggart and Bowen. Hildy warns that ‘it ain’t worth it. Revenge always turns sour”, Hogue replying “There’s some things a man can’t forget – and I’ve got two of them”.

Their idyll is further interrupted when Reverend Stone arrives seeking sanctuary from Claudia’s husband who is aiming to kill him for interfering with his wife. Hogue reluctantly covers for Stone but later that evening Hildy tells Hogue she will be leaving the following day, her happiness with him too much for her to endure anymore.

After one last night of passion she leaves the next morning, the Reverend also bidding au revoir later that day. Hogue stays on, informing the absent Taggart and Bowen that “I’m here. Waiting”.

Then one day they turn up, stepping off the stage without a care in the world and dressed up like a couple of dandies. Hogue is unexpectedly all sweetness and light, inviting the wary duo “come on and have a drink of the best damn water for 50 miles around”.

Luring them in with tales of how rich he is he sends Taggart and Bowen on their way but invariably they return, determined to find the money the stagecoach company pays to Hogue which he has told them he refuses to keep in a bank.

Alone at a seemingly deserted Cable Springs, the two men start digging a large hole where Taggart thinks the money might be buried but all they find is copper coins.

Hogue then turns up, telling them to climb out of the hole with their hands up. They taunt him, reminding Hogue that he didn’t take the opportunity previously to shoot them before they got the drop on him and left him in the desert and that he was probably still yellow.

After Hogue throws a couple of live rattlesnakes into the hole they’re forced to climb out and face their old and now very rich and heavily armed ex-partner.

Hogue orders the two men to strip down to their underwear, take off their boots and start walking out into the desert. When Bowen points out that “there ain’t no water” Hogue replies “Now don’t that sound familiar”.

Taggart is having none of it but as he goes for his gun, taunting his ex-partner that he doesn’t have the guts to shoot, Hogue contradicts that notion and kills Taggart outright.

A snivelling Bowen tries to run but Hogue puts everything on hold when an automobile suddenly shows up and drives right past without stopping. Realising it’s the end of the trail for both Hogue and Cable Springs he relents and orders Bowen to bury his dead partner in crime.

When Ben Fairchild turns up with the mail Hogue informs him he’s off to San Francisco and from now on Cable Springs will be run by Bowen instead. Before the matter can be settled Hildy suddenly turns up in an even more classier automobile than the one seen previously, prepared to take up with Cable again.

Fate then steps in when Cable accidentally releases the brake on the car whilst gathering his things to go with Hildy, the vehicle then runs him over.

Knowing he is now near death Cable requests that the Reverend “preach me a funeral sermon”, demanding “don’t make me out no saint, but don’t put me down too deep”, adding that “it’s not so much the dying that you hate, it’s not knowing what they’re going to say about you”.

Stone delivers a eulogy that takes into account all of Cable’s strengths as well as his foibles, finishing with the statement “Take him Lord, but knowing Cable I suggest you do not take him lightly”.

The mourners bury Cable in his beloved desert, the grave inscribed with the message “Cable Hogue – He Found This Water Where It Wasn’t. RIP”.

The film, and most definitely the ending, can be open to interpretation on so many levels and indeed has been done so by various film critics and scholars.

I quite like the comment by Fred Guida that “Hogue is one of a dying breed, the type of rugged individualist who helped tame the west, but who lives to see it overtaken by the march of time, and, in the end, is laid low by that unstoppable harbinger of progress, the automobile.”

In his interview for Playboy in 1972 Peckinpah states “I’ve never picked any of my films. Except one, The Ballad of Cable Hogue. That’s the only movie I ever picked to do”.

According to author David Weddle in his book “Sam Peckinpah ‘If They Move… Kill ‘Em!” Peckinpah “frequently referred to it as his favourite film, and it’s easy to see why, for it exposes the tender inner core of this turbulent, often misunderstood artist”.

Peckinpah held Warner Bros responsible for the failure of “Cable Hogue” at the box office. Accusations flew back and forth from both sides and, inevitably, director and studio parted company.

One more Peckinpah found himself out in the cold but not for long. The success of “The Wild Bunch” would keep him gainfully employed for the next few years. He wasn’t finished yet.

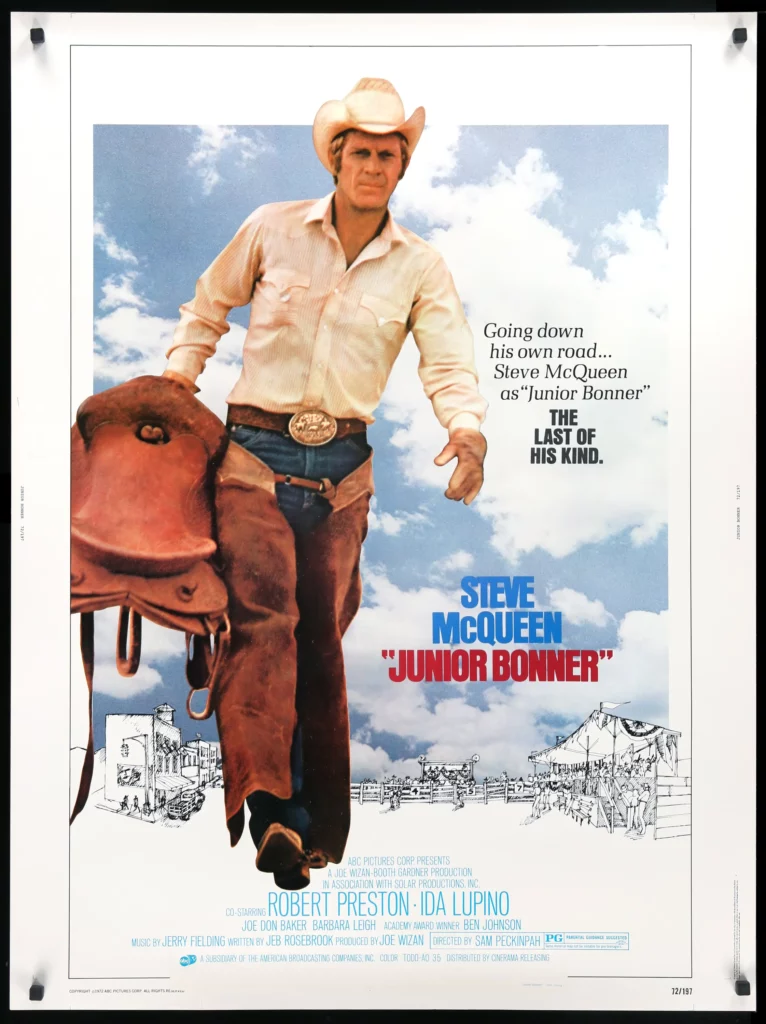

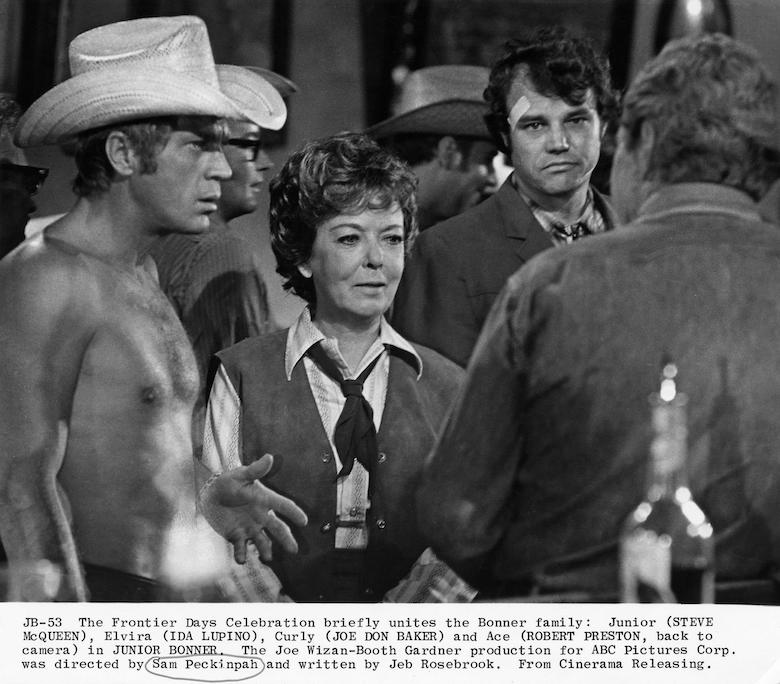

Junior Bonner

“Junior Bonner” may be a modern-day or ‘eco’ Western to casual film fans but at its centre lies the beating heart of a bona fide Western in all but name.

Released in September 1972, the film starts with a montage of rodeo action in which Junior aka J.R. (Steve McQueen) is thrown into the air whilst clinging on to a huge wild bucking bull by the incongruous name of Sunshine before then retiring to his trailer and taping up his bruised ribs.

The first words out of his mouth are “Maybe I ought to take up another line of work”, establishing right from the start that J.R., like so many Peckinpah protagonists before and after, is the wrong man at the wrong age in a profession that is just never going to let him retire gracefully.

J.R. hits the road pulling with his horse and trailer and goes to visit his father Ace (Robert Preston) in the Arizona town of Prescott, only to find Ace’s homestead is being pulled down in the name of progress.

Whilst J.R. faces down a digger laden with what’s left of his father’s home, Ace lies in a hospital bed arguing with his other son Curly (Joe Don Baker) about Ace’s get-rich-quick schemes that never amount to anything.

Curly tells his dad he’ll give him an allowance and then leaves, the source of Curly’s philanthropy revealed via a TV advert in which the younger son peddles real estate. Ace expresses his opinion about Curly’s livelihood by smashing the TV screen.

J.R. signs on for the local hometown rodeo, borrows a few dollars from rival rider Red Terwilliger (Bill McKinney) then retires to the local bar where he meets up with the owner Del (Dub Taylor) and rodeo organiser Buck Roan (Ben Johnson).

J.R. tells Roan he wants to be drawn to ride Sunshine again and, if he can hang on for just eight seconds, he might stand a chance of winning enough money to pay for his next rodeo. Roan tells J.R. he’s not the rider he used to be but J.R. insists on account of he’ll be performing in front of a hometown audience. Roan gives in when J.R. tells him he’ll ride Sunshine for only half the prize money available.

J.R. visits his mom Elvira (Ida Lupino) who informs him that her estranged husband is in hospital after crashing his car whilst under the influence. She also lets on that Curly is responsible for having turned Ace’s homestead into “ a gravel pit” after Ace sold out to Curly in order to finance an expedition to mine for silver.

J.R. is not too impressed that his brother short-changed their father by only paying $15,000 for twenty-six hundred acres of prime real estate land in order to turn it into a mobile home park.

Later that evening after dinner at their mother’s house J.R. brings the matter up with Curly who offers him a job to help sell the land bought from their father. J.R. puts an amen to the conversation by punching his brother through the porch window.

The following day Ace discharges himself from hospital and heads off to the rodeo where he borrows J.R.’s horse and rides it back into town to take part in the Rodeo Day parade. J.R. turns up a few minutes later and attends the draw in which Buck Roan has put in the fix for him to ride Sunshine.

J.R. joins the parade, taking a ride on Curly’s float, his younger brother promising to whip his ass at a later date for sucker punching him the night before. J.R. and Ace ride off to get a drink whereupon his father tells his son about his latest pie-in-the-sky venture, hunting for gold in Australia. All he wants from J.R. is to grubstake his old man for $5,000, forcing his son to tell him he’s broke.

J.R. takes his first turn on a horse at the beginning of the rodeo, getting thrown after failing to hang on long enough. As he limps away he catches the eye of a beautiful woman by the name of Charmagne (Barbara Leigh).

In the next bout, he wrestles a steer to the ground in under ten seconds, winning the approbation of both the crowd and Charmagne. J.R. and Ace work together to milk a cow whilst Curly and his wife Ruth (Mary Murphy) look on in bewildered disdain at the antics of two grown men.

The Bonner family has a strained reunion in Del’s crowded bar during the rodeo intermission, a meeting that becomes even more strained when J.R. and Curly decide to settle their differences with another fight.

J.R. then refuses Curly’s request to reconsider his job offer, telling his younger brother he needs to go down his own road. Curly replies with a verbal knockout punch, confiding that whilst he’s working on his first million J.R. is ‘still working on eight seconds’.

More trouble arises when Charmagne enters the crowded bar with her beau, J.R. setting things off by asking her for a dance. Her boyfriend warns J.R. he can only have one dance which he honours. He then hands Charmagne over to fellow rodeo rider Red Terwilliger, the enraged boyfriend then kicking off and initiating the inevitable bar fight which, considering this is a Sam Peckinpah film, is remarkably light in terms of bloodletting.

Whilst all this is happening J.R. and Charmagne get better acquainted in the privacy of a cupboard in the bar. At the same time Ace and his ex-wife get reacquainted after Ace confirms he’s finally leaving for Australia, the couple saying their goodbyes in privacy.

J.R. returns to the rodeo for his appointment with Sunshine, the announcer informing the audience that the prize money for riding the bull for a full eight seconds is $950.

In front of an admiring crowd including Charmagne, J.R. manages to hang on to Sunshine for the requisite time. After saying his goodbyes to Charmagne and then his mother, J.R. buys his dad a one-way ticket to Australia with his winnings then hits the highway once more for the next rodeo.

Peckinpah and McQueen teamed up on two movies, “Junior Bonner” followed a couple of months later in the same year by “The Getaway”, a tough crime drama that scored big at the box-office and leaving “Junior Bonner” to eat dust in its wake. That’s a shame really because McQueen is on top form as the loner J.R., delivering a subtle performance every bit as impressive and more so than his turn as ex-con Doc McCoy in “The Getaway”.

It’s still an underrated Peckinpah film to this day and, as the director once remarked, “I made a film where nobody got shot and nobody went to see it”.

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid

There are approximately four versions known to be in existence for “Pat Garret and Billy the Kid” out there somewhere – the original cut by Sam Peckinpah which was rejected by the studio (MGM), the theatrical version released in 1973 in place of Peckinpah’s version, a Turner Preview version, presumably made for viewing on TCM back in 1988, and a special edition released for home viewing in 2005.

For the purpose of the article, I am using this latest restoration for reference purposes. It is not in itself the definitive version – does one actually exist? – but in the end, you pays your money and takes your chance.

Here follows a synopsis of that version.

A title card declares the year is 1909 as an ageing Pat Garrett (James Coburn) argues with a couple of men including John W. Poe (John Beck). Poe looks on coldly as Garrett is assassinated, his body rolling in the dust.

The film then flashes back to 1881 in Fort Sumter where Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson) and members of his gang are, in the absence back then of the American Humane Society, happily blowing off the heads of live chickens, the scene interspersed with slow motion shots of Garrett dying twenty-eight years later.

Garrett has come to tell Billy he intends working for the law and will be hunting his old friend down from now on, informing the Kid that “the electorate want you gone”. When asked why he didn’t just shoot Garrett there and then he, Billy, replies “because he’s my friend”.

The day after his now ex-friend makes sheriff he surrounds Billy’s cabin with a posse and fills it and two of Billy’s companions including Charlie Bowdre (Charles Martin Smith) full of holes. Billy is carted off to the Lincoln County jail and incarcerated awaiting execution.

He is guarded by old gang member J.W. Bell (Matt Clark) and Sheriff Bob Olinger (R.G. Armstrong at his manically religious best), the latter goading the Kid about his imminent demise and that his shotgun is crammed full of “sixteen thin dimes”.

It’s not too long before the Kid gets the upper hand, pulling a hidden gun on Bell and shooting him in the back before turning Olinger’s gun on the raving lunatic of a lawman with the suggestion that he “keeps the change”.

Watched by store shop assistant Alias (Bob Dylan) the Kid rides unhindered out of town as a group of young children swing playfully on the rope of the gallows specially built for Billy.

Garrett returns to town and, in the wake of Billy’s escape, employs a horse thief and hired killer by the name of Alamosa Bill Kermit (Jack Elam) to try and pick up the Kid’s trail.

There then follows a strained meeting with his wife Ida (Aurora Clavell) who berates Garrett for having sided with the powerful collective known as the Santa Fe Ring who, along with landowner John Chisum (Barry Sullivan), want Billy the Kid taken down under the name of the so-called law.

Garrett then meets with Governor Lew Wallace (Jason Robards) and members of the ring who no longer want the Kid on the loose. They offer him $500 cash with a further $500 to recapture his old friend.

He tells them he aims to do just that but in the meantime, they can take their money and shove it where the sun doesn’t shine. Also present at the meeting is John Poe, sitting silently at the next table.

Billy meets up with his gang back at Fort Sumter but the reunion is interrupted when three strangers try to kill the Kid. The trio are quickly despatched, one of them via knife in the neck, delivered by Alias who has decided to join the cause.

Meanwhile, Garrett visits an old acquaintance of his, Sheriff Baker (Slim Pickens), looking for information on the Kid. Baker tells him two members of Billy’s gang, including ‘Black’ Harris (L.Q. Jones), are in the near vicinity.

Along with a gun-toting Mrs. Baker (Katy Jurado), they pay a visit to Harris and his companion and in the inevitable shootout both gang members are killed but not before the sheriff is shot in the gut. He wanders down to the river accompanied by “Knocking On Heaven’s Door” on the soundtrack and waits to die.

John Poe suddenly turns up uninvited at Garrett’s night camp and tells him he is now a deputy appointed by Wallace to help find the Kid. They both then meet up with Chisum, Garrett thanking the landowner out of earshot of Poe for the ‘loan’ Chisum had given him for his efforts in apprehending Billy.

On the advice of both Paco (Emilio Fernandez) and Alias, Billy decides to head over the border for a while until things cool down whilst Garrett sends Poe off to track down the Kid in Roswell.

Whilst Garrett then visits another old acquaintance, a saloon owner by the name of Lemuel (Chill Wills), the Kid stops by to meet his old friend Horrell (Gene Evans) who by coincidence is dining with Alamosa Bill.

Billy and Alamosa take a walk outside and ‘get to it’, Billy getting the upper hand and shooting Alamosa dead.

Back at Lemuel’s saloon three of Billy’s gang, Alias, Beaver (Donny Fritts) and Holly (Richard Bright) show up, the initially friendly meeting taking a turn for the worse when Garrett pushes Holly into making a move with a knife with deadly consequences for Holly. The sheriff tells Alias to inform the Kid that they all had “a little drink together”.

Whilst out on a turkey shoot with Alias the Kid chances upon his friend Paco being attacked by a couple of his old gang members who are now in the employ of Chisum.

Paco is fatally shot so, after finishing off most of his former companions, Billy returns to Fort Sumner in order to face down Pat Garrett once and for all.

Poe interrupts Garrett who is enjoying a sixth-some in a bordello with a group of young ladies including Ruthie Lee (Rutanya Alda) who has informed the sheriff that Billy has returned to his old haunt.

Garrett instructs a disgusted Poe to find Sheriff Kip McKinney (Richard Jaeckel). Garret subsequently ‘invites’ McKinney join him and Poe in paying a visit to the Kid at Fort Sumner, a reluctant McKinney ruefully commenting “I hope they spell my name right in the papers”.

The final confrontation eventually comes to pass, Garrett locating Billy’s whereabouts late at night at the house of Pete Maxwell (Paul Fix). Before making his move he encounters Will (Sam Peckinpah), a coffin maker who refuses a drink from Garrett before telling him to “get it over with”.

The sheriff cautiously enters Maxwell’s place and, hearing the sound of Billy and his girlfriend Maria (Rita Coolidge) in bed together waits for the couple to finish their lovemaking before lowering the curtains on Billy the Kid.

Billy gets out of bed just as Garrett is about to make his move and walks outside to look for some food. McKinney realises the Kid is just a few feet away from where he and Poe are concealed.

Too scared to take a shot McKinney tells Poe to do it instead but he is also too scared to finish the outlaw off. Catching sight of the two men Billy slowly backs into the house just as Garrett approaches him from behind.

Billy turns and Garrett shoots, killing the Kid instantly. Disgusted with himself Garrett then blasts away at a mirror, destroying his own image in the process. Garrett then lays into Poe for trying to cut off the Kid’s trigger finger as proof of his death.

A group of Billy’s disciples including Maria and Alias gather in the morning light around the corpse of the Kid whilst Pat Garrett rides away, a young child throwing stones at his back.